Maya Dvash: Legend tells of a Samurai sword collector who constantly strived to refine his collection. Whenever he had acquired ten cheap swords, he would replace them with one unique and expensive one. At the end of this story, all that remains in his collection is a single, ultimate sword. How did the story of your collection begin?

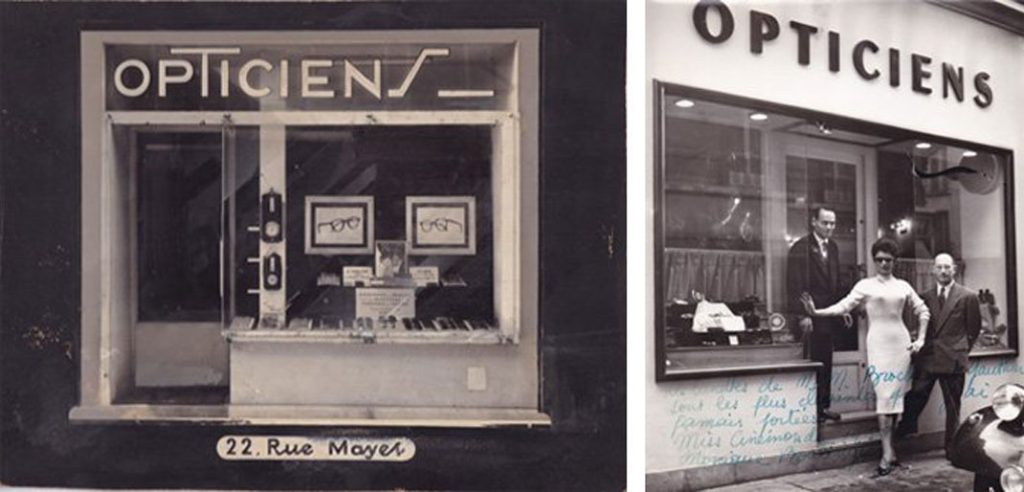

Claude Samuel: My collection began with an inheritance I received from my father. It is based on eyeglasses from the luxury eyewear chain Meyrowitz, which my father sold when we moved from France to Israel. When I arrived here, I began with one display window on Rembrandt Street. Only once I moved to the store on Dizengoff Street did I begin to wander through markets, meet collectors, and collect additional items. Ory, my partner in life, was already involved in the design world, and encouraged me to become a collector. Today, I get regular updates on the Internet, study the catalogues of the world’s most important auctions, and purchase items that interest me.

MD: Still, going back to the story about the swords, what kind of a collector are you? Do you search for that one unique object or for a large variety?

CS: For me, every item has meaning within the collection. Every pair of glasses is another link on the chain that tells the “story” of the invention of glasses from its inception to the present. My goal in curating the collection is to narrate a historical story. This process can be compared to a figurative painting – every detail is an inseparable part of the composition, and when something is missing its absence is acutely felt. For instance, I am missing a very important pair of eyeglasses from the Middle Ages, from the thirteenth century – a very rare and expensive item.

MD: Are they “all your sons”? Do you equally cherish all the eyeglasses in your collection?

CS: No. I do have some favorite children. I especially like a certain art?nouveau monoclethat I found by chance at the flea market in Paris. I am also very attached to my father’s glasses – a pair I made him in the 1980s, and to a pair of protective goggles that appeared in the French film l’Aveu, starring the actor Yves Montand.

MD: Many of the glasses really tempt one to try them on. Do you ever put on a pair from your collection and wear them out on the street?

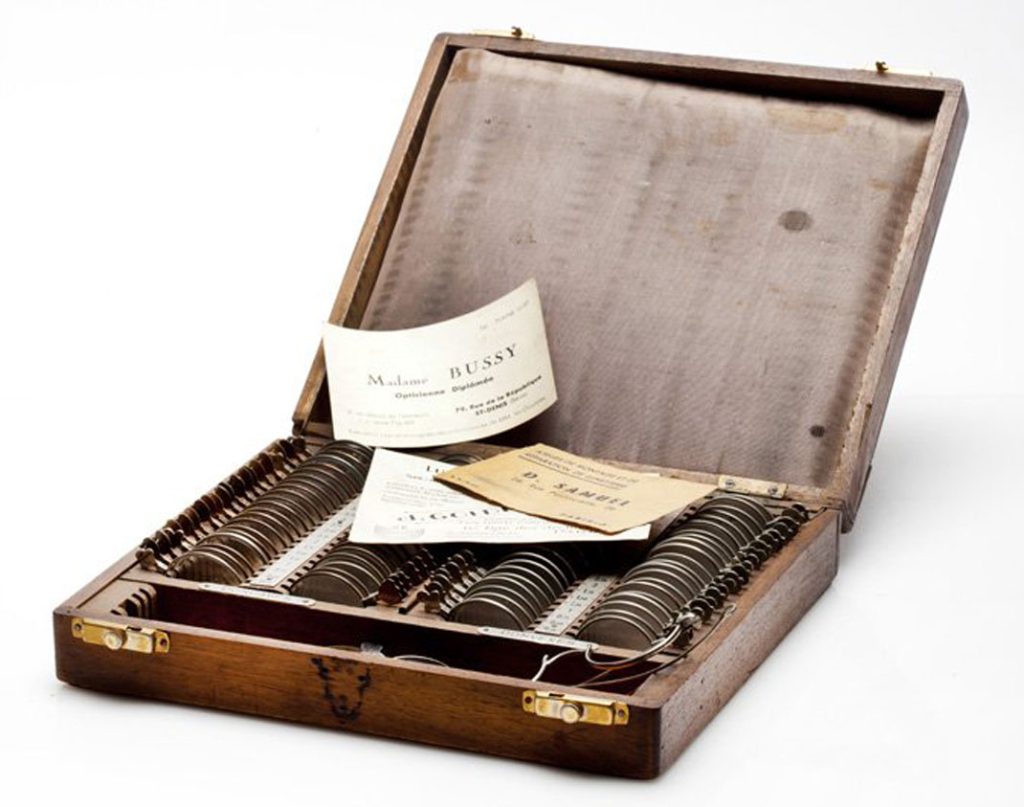

CS: No. Never. But to go back for a moment to the collection, at the moment my goal is the realization of this exhibition. Apart from my grandmother’s case of lenses, which is included in the show, and a small number of other items, I have no sentiments towards the collection. I would be ready to dispose of most of the items after the exhibition. I can certainly imagine this display case being replaced by works of art. I would feel fine about that.

MD: So you are not one of those obsessed collectors whose entire life revolves around their collection.

CS: Not at all. I’m not that obsessive, nor do I have the time for that. What I am interested in is the big picture. That is why I also collect things I don’t like. Things I value because they will represent a certain period when seen in the future. I recently purchased two Cartier items, which in my eyes are extremely ugly, for the sole reason that they represent, for me, the beginning of the connection between jewelry and eyewear – a significant aspect of the way glasses developed over time.

MD: Culture, then, seems to be the key word that shapes your construction of the collection. In my view, collections link the past and the present into a continuum – their meaning lies in the fact that somebody collects these things.

CS: I agree, and I have a story that supports your argument. The first item to enter the collection of Yad Vashem was a bag with glass shards and metal parts that were once a pair of eyeglasses. The woman who brought them said that when she and her mother were separated in Auschwitz, at the very last moment she was able to take her mother’s glasses. I tell this story because I see this item as a witness to an intimate yet also universal and historically important moment. Details are the history of people; they are the ones that, ultimately, tell the human story.

MD: If we pursue the connection you mentioned between Jews and eyeglasses, the research we conducted in preparation for the exhibition revealed that Jewish families often abandoned other professions to work in the eyeglass business. What, in your opinion, steered them in that direction?

CS: I believe that Jewish families chose to work with glasses for the same reason they chose to work with money. Both money and medicine (the field to which eyeglasses belong) ensure a constant source of income independently of one’s location. This was a profession that enabled families to move from one place to another without having to change their profession.

MD: So glasses are a cultural link, and glasses are also a source of income. As the fourth generation in a family of optometrists, what do they represent for you? How do you treat them?

CS: Glasses are the only accessory capable of maximizing man’s physiological capabilities. A piece of jewelry or a belt do not allow us to exploit the full potential of a specific body part. The same realization of potential may perhaps be identified in the effect that sports shoes have on runners.Yet beyond this physiological aspect, eyeglasses are, for me, a personal and intimate accessorybelonging to a client, and not just an object. I am intentionally using the term “client” rather than “person,” because this is the context in which I meet people – as clients coming for an eye examination. In the course of the examination, I aspire to become deeply acquainted with the person seated before me, since choosing the right pair of glasses involves an overall understanding of the client’s needs: what he does for a living; how he looked before I met him; how he would like to look; and whether he can be drawn out of his shell – that is, coaxed into wearing a pair of glasses that will cause him to look completely different. People sometimes conceal, or are simply unaware of, various aspects of themselves, and my role as an optometrist is to discover them. Even a basicquestion such as whether the client sees or not cannot be taken for granted. People sometimes pretend they need prescription glasses, or, by contrast, conceal the fact that they do not see well.

MD: But today glasses are no longer a necessity. One can opt for a laser operation that does away with the impairment and the need for corrective eyewear.

CS: That is true. Originally, glasses were indeed designed to correct a vision impairment, but that is not the only reason people wear glasses. Like jewelry or makeup, glasses produce a certain image. When someone buys a black BMW car, he is interested in projecting a certain social image. A brand constructs an identity, and to a large extent also creates a certain affiliation, and such brands also exist in the world of glasses. The following story is an example of the parameters I take into consideration. When Leah and Yitzhak Rabin first came to me, Leah immediately chose a Cartier frame. I told her that it was impossible for a socialist prime minister to wear such a frame. That reminds me of another story, about a client who did not know myfather was Jewish, because he had changed his name to Daniel Gauthier. She told him she had to hide her eyes behind glasses because they were ugly. When her husband pressured her to reveal the true reason, she explained that her eyes were wet, “like Jewish eyes.” People want to wear glasses for all sorts of reasons: some want to blur or conceal some facial feature, while others simply want to look different. Well? known individuals sometimes choose unusual glasses as part of the image they wish to project.

MD: So what, in this world, is identified with whom?

CS: Round glasses are usually identified with intellectuals. Even Freud wore round glasses, it was very fashionable at the time. Something about them communicates the sense that the person in question is unapproachable because he is highly intelligent. I really like round glasses. In contrast to other eyewear boutiques, we hold lots of round frames, but most people prefer other shapes.

MD: I read that during a certain period large eyeglasses were identified with Jews or usurers, and that people who wear sunglasses all day want to project the image of a leisurely existence.

CS: I don’t know about the affinity between Jews and large glasses. But among the Mandarins in China,for instance, large glasses are associated with wealth. As for sunglasses, fashion shows todayare filled with people wearing large sunglasses in a closed interior. In my opinion, they want tocommunicate that they are “here but not here.” Such glasses create a kind of detachment from one’s surroundings – I can’t be approached, because I’m protected.

MD: In the end then, glasses are a form of protection.

CS: Not exactly. They are also a form of protection, but above all they are a form of self?expression

MD: Speaking of self?expression, do you also design glasses?

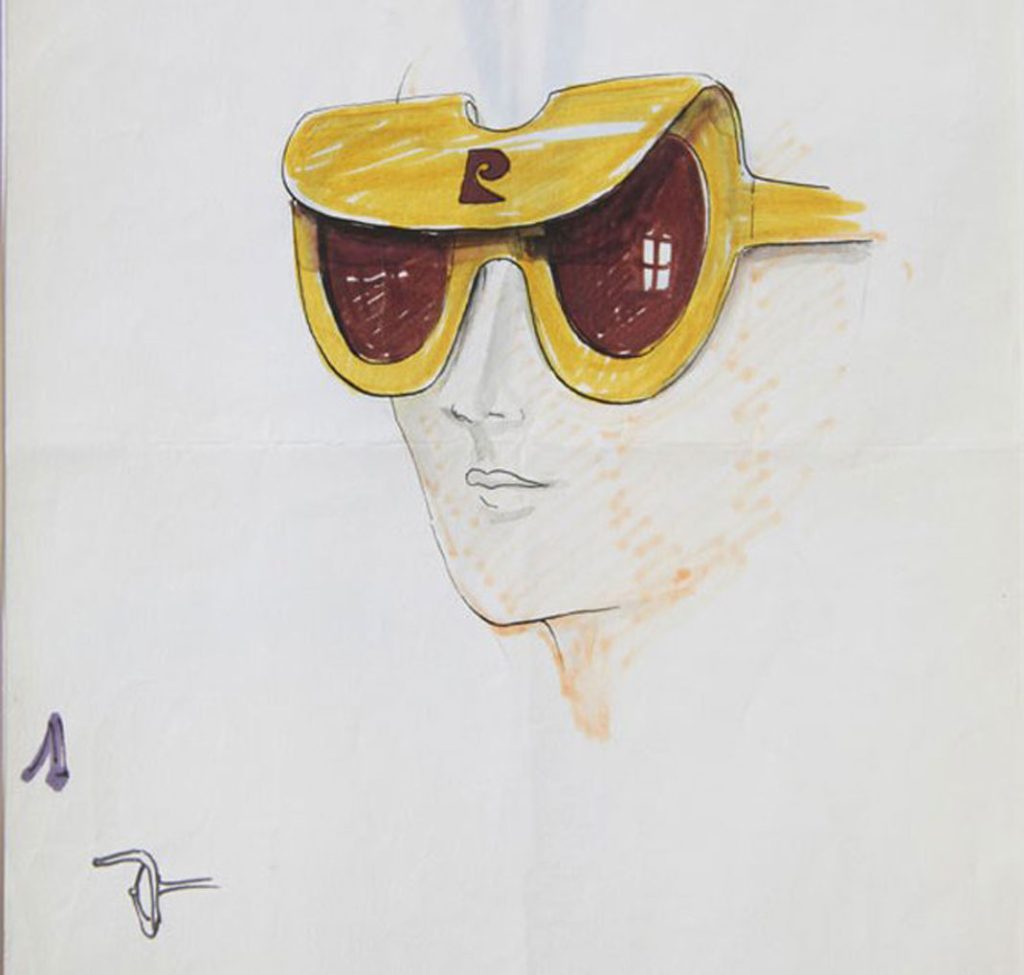

CS: I spend a lot of time at large international exhibitions, studying what is out there. I know what I like, and know how to put my finger on what is missing. Designers have lost the sensitivity to materials and forms. This was why, six or seven years ago, I commissioned a German company to create a certain model according to my specifications. I don’t create drafts or sketches as my father did, but I explain how I want the frame to look. Frames that are manually formed, polished,or assembled are no longer common today.

MD: You seem to suggest that an optometrist, like eyeglasses, is composed of two parts: the frame represents the optometrist’s aesthetic side, his ability to fit frames to different personalities. The lenses, meanwhile, represent his connection with the personal and medical aspects and with the clients’ medical and physiological needs.

CS: True. I was lucky to be trained by my older brother, who was an optometrist and a lecturer in optometry. Up until the 1980s, optometry was outlawed in France. Only eye doctors were allowed to conduct examinations. During that period, my brother and three of his friends opened a clinical optometry shop, and they were arrested and put on trial. In comparison with what I do, clinical optometry took a holistic, mind?body approach. I chose to focus on the more practical and scientific aspects. I conduct examinations as I see fit, and in this sense I am very different than the majorityof optometrists.

MD: How are you different?

CS: There is no “right and wrong” when conducting an eye examination. It is not an exact science. There is a general outline that begins with becoming acquainted with the client, followed by a physiological examination that ends with a summary of the insights gleaned during the examination. In some cases I know we have deciphered the overall picture – like an artist recognizing the moment in which he has completed a work. In other cases, however, I conclude the examination unsatisfied, because I feel I missed something. That is why I take care to devote sufficient time to each client, until I know that “that’s it.”

MD: Interesting. Anyone who has ever undergone an eye examination gets the impression that there are clear rules. You either see well or you don’t.

CS: I believe that in order to reach people, one must get to know them first. I owe this insight to my father, who had the gift of knowing how to communicate with people as well as an artist’s hands. People often tell me after the examination that they were never examined in such a way. My father’s family had specialized in eyeglasses for several generations. My paternal great?grandmother, Marie Norman, sold cheap jewelry and eyewear in the Marais neighborhood of Paris. Her daughter Judith Samuel, who was my grandmother, was an optometrist who walked through markets, examiningpeople seated in cafes and workshops and writing them prescriptions. The case of lenses included in the exhibition belonged to her. When my father was a child, he would help her cut the lenses she had bought with a stone polishing tool, working alongside her in thefamily kitchen. When my father was 14, he left school and joined the French army. When he realized that the army was collaborating with the Nazi regime, he left and joined the Resistance. During the war, his talent enabled him to forge documents and permits – a job that demanded precision and refined handling just like the work of a watchmaker or goldsmith. He was self? taught. After the war, my father worked with Pierre Cardin for twenty years. They spent many hours together. He designed unique pieces for Cardin, such as glasses for runway shows, but also eyewear for serial production, such as the folding glasses that became popular in the 1960s. One example is a patent my father invented, for which there was a special factory and production line. I was fortunate to receive an entire collection from the history of Cardin – including items, sketches, and photographs. Almost nothing is missing. I had no choice but to learn the secrets of the trade from my father. I was the family’s black sheep – an antiinstitutional type who was thrown out of several high schools. While studying at a school in the sixteenth arrondissement of Paris, in the 1960s, I was taken with Maoist political activity. One of the leaders adopted me, and I became involved in politics. We sat in his house reading the Red Book. It was a period of very violent activity against the French fascists. We organized loud, violent demonstrations, threw Molotov cocktails, and got into fights.

MD: So how did the black sheep end up studying optometry?

CS: My very staid family obliged me to study a profession. I was initially sent to a vocational school to study precision mechanics. But the thought that this was what fate had in store for me caused me to flee. The fact that I was very close to my father finally led me into the field of eyewear. At the same time, my father and I had both always wanted to work in a profession that had to do with humanitarian concerns.

MD: Where did this rebellious spirit you shared with you father come from?

CS: I can only speak for myself. I have a hard time identifying where exactly it comes from. It could be a reaction against the family background, which was aristocratic, bourgeois, and wealthy, and which opposed many of the values I believe in. My immigration to Israel enabled me to turn a new page.

MD: In the past, you spoke about your father having to give up his Jewish identity. You too were born as Claude Gauthier. But you are now Claude Samuel. Is that another form of rebellion?

CS: My father was a Holocaust survivor who lost everything. He wanted to commit suicide after the war. He had nowhere to go. He became close to my mother’s extremely wealthy family. When they told him “You are no longer a Jew, you are a Gauthier,” they were in fact asking him to abandon Judaism. In order to be a successful businessman, a successful person, he had to forget the Holocaust and everything he had done and carried within himself. I am Jewish, but also French. The fact that my grandmother had to wander through markets in order to make a living is something I perceive as a form of humiliation. Sadly, I did not know her. She was murdered in the Holocaust. But I see her as a victim. And for me victimhood is an enemy. There is no reason for oneperson to be the victim of another. I don’t want to be a target. I sometimes wonder whether the fact that I was born a Jew means that I must bear the brunt of the Jewish people and cope with what life here confronts us with – vis?à?vis the Palestinians, Christianity, Judaism. I feel that my background means I must take responsibility to contribute and help. I work with refugees in the territories and in Ethiopia. I try to help as much as I can. At the same time, it is difficult to define exactly what makes me undertake all of this activity.

MD: You define yourself as a Zionist who is committed to humanitarian causes. I know that, among other things, you own a large collection related to the Dreyfus Affair. You are also French, and a Jew, and your identity has additional aspects. How do you resolve all of these conflicts in your personality?

CS: It is a great privilege to be the heir of such a family legacy, yet at times I feel it is another burden I must bear. As a French Jew, I carry the lessons of the Dreyfus Affair. Dreyfus was an example of an injustice committed against an individual, yet this individual represented an entire people, an entire segment of the French population. The Affair caused a tremendous schism in theJewish community – Jews who wanted to remain part of the French nation could not support Dreyfus, because such support amounted to removing oneself from French society. My identity is part of thisconflict: On my mother’s side, I am part of a bourgeois, intellectual family that sought to assimilate into French society. At the same time, I am a Zionist who upholds humanitarian values.

MD: Indeed, while your humanitarian activities involve encounters with underprivileged individuals, your boutique is located at the heart of Tel Aviv’s bourgeois cultural center. And most of your clients are quite wealthy.

CS: True. But I have an interesting story in this context. When I was volunteering in Ethiopia, I noticed that these needy people never said “thank you” after their examination. At first I found that unpleasant. I later understood that from their perspective, if a person can help, he should help. It is totally normal to help others, that is the way it is supposed to be. In Western culture, by contrast, one must express thanks, pay, or reciprocate with something. Here, if there is nothing given in return, it is considered wrong. There, it is natural to help one another. That is what my father did in the French Resistance and that is what I am doing here. As long as I can, I will help as much as possible. At the same time, I grew up surrounded by businesses like Meyrowitz. I wanted to imitate what I had seen in France. But when the opportunity arose for me to open a Meyrowitz store in Tel Aviv, I declined. It’s true that today everything here looks quite chichi, but I began from zero and initially did everything myself. In general, I always aim high. In the current economic reality, whoever remains average simply fails.

MD: As a fourth-generation optometrist in the eyewear business…

CS: Business is not the right word in my opinion. I believe tradition is a better term.

MD: So, according to you, it is not a business, but rather a tradition. Yet when we spoke about this in the past, you chose the term “guild,” even though we are not speaking of a shop passed on from father to son, but rather of a form of expertise and passion transmitted from one generation to another. Guilds have existed since the Middle Ages. What defines them is expertise in a certain area and a shared ethical code, as well as high expectations from their clients. If a a stone broke loose from a building and killed a passerby, the builder was condemned to death. Expertise was a supreme value, and failure to meet the standard resulted in punishment. That world is very far from today’s dominant worldview.

CS: Yes. But not from my worldview… When I hire workers, I always tell them about my family past. In certain enterprises, you can see workers who came there as children and remained there until their death, and that is something that is sorely missed today, especiallyin Israel. There is no replacement for the expertise of the leather workers who craft pieces for Hermès, for instance, and who specialize in saddles or shoes. That is what I try to offer. Careful personal attention during the examination, as well as when clients receive their glasses and even two weeks later, when we call to ask how they feel. Success must involve an investment. That is the essence of a guild.

MD: As part of the research we conducted in preparation for this interview, we sought information about traditional Jewish stores and businesses passed on from one generation to the next. We found much information about the Moskot family, whose eyewear brand recently celebrated its centennial anniversary. It still exists today in New York, and a member of the fifth generation is an industrial designer. It’s interesting to see how design finally enters the picture.

CS: In my family, tradition is given expression in a different manner. My oldest brother, Olivier, was a full-fledged optometrist. He worked in Jerusalem after immigrating to Israel, but was a poor businessman. He understood neither business nor fashion. My father was everything I already told you about. And I combine the two. For the past 30 years, I have been conducting eye examinations at Tel Hashomer Hospital for underprivileged populations. At the same time, I am building, expanding, and developing a collection that some may define as very elitist.

MD: Each one of you is a somewhat different version of the same story. You each hold expertise of the kind we mentioned in the context of a guild, while specializing in different aspects of the same professional field.

CS: Yes. But what is important for me is what I carry with me. I view my father as a hero. It is rare to find people who know how to save other people, to construct something that did not exist before, and still to remain modest.

MD: You noted that your father was very dexterous and engaged in a lot of manual work, as did your grandmother. Today, the process has been inverted. The measurements of a client’s face are entered into a computer program; he chooses a color, and receive glasses printed especially for him in a 3D process. How do you view this technology? It seems to counter everything we have spoken about thus far.

CS: For me, conducting an eye examination is like sewing a saddle. One must pause, check, make corrections, and observe. True, most things today are no longer donemanually. The new technologies enable us to custom-fit eyeglasses for every client. I am not against this, and there are certainly also technologies that I am not familiar with. But one of the significant things, from my perspective, is the way the glasses sit on the face. They must be part of the face, and respect the structure of the nose and ears – and this requires a human touch. There are still areas in which there is no replacement for the human hand – a machine or computer can never beas sensitive as personal, human touch.