How did you begin to work on the bow, and why exactly bows?

I began working on bows during the first lockdown. I bought flat bamboo skewers and began to play, using them as raw material. But my engagement with bows began way before then. When I began to make sketches from the skewers, I was intrigued by the energy embodied in the bow, an issue that had arisen earlier in the studio. As I was working with the skewers that I bought, each one led to another idea. That’s how the collection formed, with each group generating another. Finally I bought up what was apparently the supermarket’s entire stock of skewers. When the first lockdown ended, I was able to get back to the studio where I examined some large models I built from wood and other materials at hand, to see how things looked. Afterwards, I constructed an entire orderly collection and transformed it into a kind of “product.” The bows on view in the exhibition are uniform in terms of their raw material. That was intentional, because this is a small exhibition with many objects, so at least the infrastructure should be uniform.

The original use of the bow is for shooting. What function does it have in the exhibition, as you see it?

As I see it, the bow is an object with internal energy. I used this energy to activate and leverage ideas. By the way, as a boy, I made a bow and used it for all sorts of “non-standard” activities.

It was very dangerous, but times were different – children made their own toys, while today kids play mainly with bought games. A game or toy like the bow I made would never be authorized as up to standard by any serious toy company today.

Which bows formed the basis of your morphological research?

At a certain stage, I wanted to intensify the bow’s power, and remembered the Mongol bow.

The Mongol bow was a composite of different materials, using to the fullest the advantages of each, which is why it was much stronger than bows made from a single material. It represents a turning point in the history of the bow, and the whole notion of “extra power” intrigued me – not to improve its shooting power, but as an independent characteristic of the bow.

Based on familiarity with the historical reference of the Mongol bow, I made several versions of my own. One of the ways through which it is possible to intensify the power of the bow is to recurve it – not in parallel, but with a specific angle, created by twisting the bow or by taking a solid raw material – a kind of square, and cut it from both sides.

A curve is actually a formal quality that reinforces the entire structure. How is it possible to weaken the raw material?

The exhibition contains several examples of weakening the raw material by cutting or flattening it in different ways. We can see in the collection that I actually examined the entire range on a continuum from power to weakening.

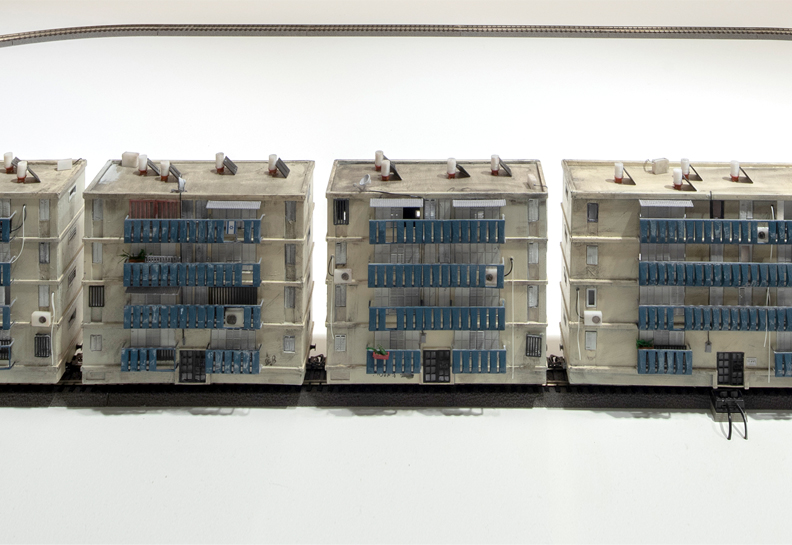

Is there a group of bows in the collection showing how the entire structure bears weight?

Yes, those resulted from my wondering how a bow could become a container, a package, or packaging – all major design concepts. How do we package something? On the surface, it seemed an unreasonable concept, but I researched the two possibilities, beginning with an experiment to have the bow “contain” a single stone, through to holding a group of things: in one case, a sort

of semi-net resulted, a weave of strings holding pieces of wood. In another case, I made a hybrid, a stone inside a kind of hole, tightly attached. In this way, several different morphologies were created. The model that is the extreme example of this inquiry is a bow that nearly ceased to be a bow because it became a means of holding, making its familiar function secondary. From a visual viewpoint, it retreated into the background, let’s say as a “supporting actor.”

We talked about sources of inspiration from the history of the object. What additional sources did you use?

Some of the bows bring to mind other objects, such as the one that looks like a very large safety pin. Both are objects that store energy: when a safety pin opens, it has a kind of springiness throughout the length of its spine and all through the raw material. I observed a certain similarity between these two icons, and attempted to match or “marry” the two, so that one side is a bow and the other side is a sort of safety pin. The challenge was how to combine the two so that it would look natural, as if they had always been like that. In any case, I can always go back and separate them to be able to say, “That’s a safety pin, and that’s a bow.”

Did you identify any other technological or morphological principles applicable to bows?

When we build a tent, for example, we fix it in place and stabilize it with tensed “strings” and stakes driven into the ground. Since the bow has a string as well as an element that increases the tension, I employed the same principle. Thus once again, a shape is formed that comes from another world of content. An additional example is posed by the traditional bow saw: to be able to cut, two strings create tension, while between the two is a small piece of wood as the stopper. I actually used the same method, and it’s possible to see this principle at work in one of the objects on display. These are two archetypes I tried to use, and you can see both objects simultaneously in the works.

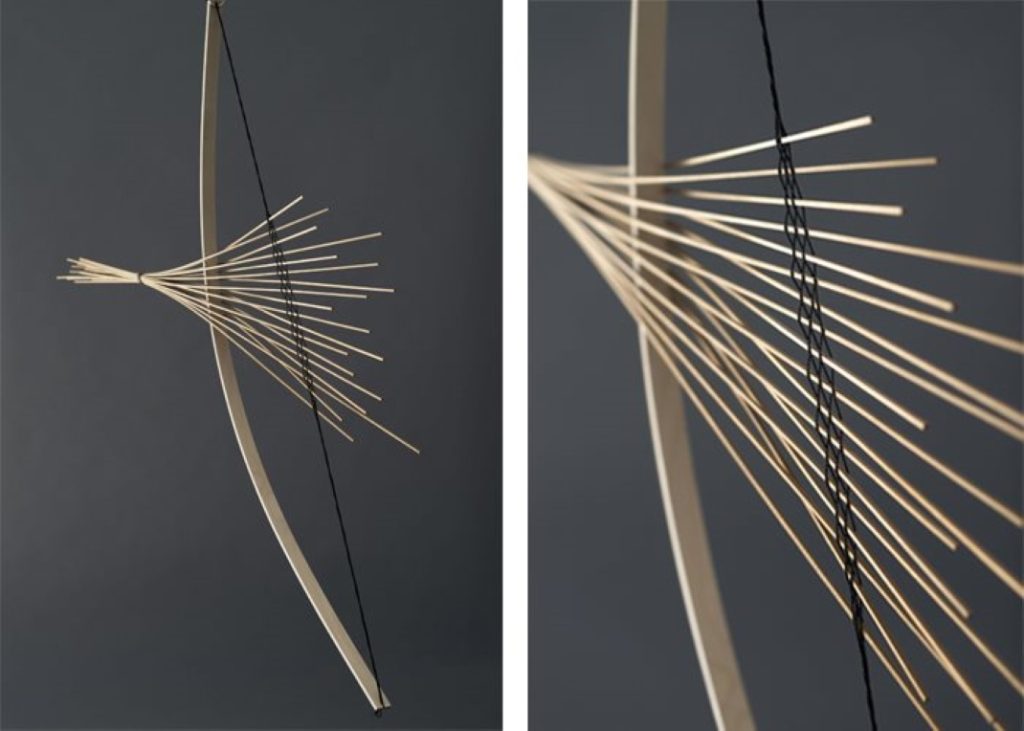

Although you had no intention of making bows for shooting, there is one group with visible “arrows”. What do you consider their function?

You call those elements “arrows,” whereas I call it a “rod” or that “something” that tenses the string. Our collective memory calls this “something” an “arrow,” but it can take on all sorts of shapes. It’s a kind of activation that enables me to change shape and take up a challenge. But what am I able to do with this “thing”? I ask myself, “What next?”

It seems that you’re working along two parallel planes: on one, you wear the “hat” of a researcher, whose subject constantly changes; the second “hat” is that of an industrial designer. Do the two sometimes meet?

Yes, they meet quite often. I would say that if I examined what I do, most of the products currently on the market arose from some sort of playful “must,” or from an engagement in morphology and technology. Even today, when I look at the bows, I say to myself, “OK, what can I get out of these to make them useful and implementable, let’s say, suited for the everyday?” I have to change my thinking in order to say, “OK, now it’s time to get working and find the end-goal, enter the world of purposefulness.” That’s a whole world by itself, and requires us to activate a totally different part of the brain. The question arises as how to take the information bank that has been created and generate something from it. We can apply the conclusions to varied spheres, from games to lighting, or furniture, fields in which I am engaged. In most cases, one thing leads to another – most are not for the consumer market, but they also resulted from a “mutation” of that very same morphological research and exploration.

The interviewer, Adi Hamer Yacobi, is researching Yakov Kaufman’s practice for her doctoral dissertation and is the curator of Kaufman’s solo exhibition, Researcher-Designer-Collector opening soon at the Design Museum Holon.