“The worst thing you can say about beauty is that it is in the eye of the beholder.” Thus, one of the world’s best-known visual communication designers, Stefan Sagmeister, chose to open the lecture he gave to the packed auditorium on the morning of the opening of the exhibition, Sagmeister & Walsh: A Retrospective. The Sagmeister & Walsh studio chooses to devote most of its work in recent years to the preoccupation with beauty. But this is not a discourse about the beauty of nature, but rather a discussion of man-made beauty, which can be assessed by clear criteria such as symmetry, proportion, harmony and balance.

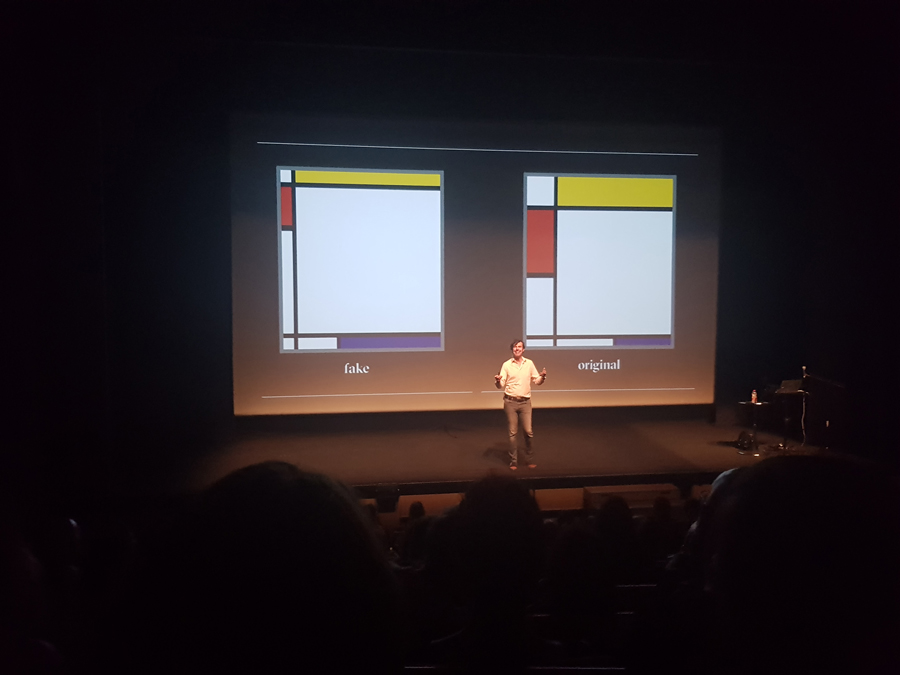

There is a vast agreement among all of us on what we find beautiful, he argues, more than is commonly thought. In a short experiment, based on the work of the British psychologist Chris McManus, Sagmeister presented the local audience with two identical Mondrian paintings: one original and the other counterfeit. When the audience was asked to identify which of them was the original – only two people were wrong. This is not the first time Sagmeister has conducted this experiment. The same test was conducted in other countries where he lectured, and according to his testimony, about 85 percent of the respondents always pass the test. In other words, although Mondrian did not base his work on precise calculations of the golden ratio, most people – even those without an artistic background or without a familiar cultural background – still recognize the aesthetic qualities of his compositions. But Sagmeister wants to prove that beauty is not just an aesthetic cross-cultural perception, but that it is also consistent regardless of a medical or a mental state: “When we lose our mind, we can still recognize beauty.”

Sagmeister’s lecture in Design Museum Holon to substantiate this claim, Sagmeister relied on an experiment conducted by Dr. Helmut Leder, president of the International Society of Empirical Aesthetics, who asked several Alzheimer’s patients to arrange well known works of art in descending order: from the most beautiful painting to the least beautiful in their opinion. When the same patients performed the same experiment two weeks later, they arranged the works in exactly the same order. “Even when most of our brain functions are gone, our sense for beauty remains, it is part of what it means to be human,” Sagmeister concluded.

Most of the well-known designers say they have no interest in beauty, the art world has abandoned it almost entirely, and it is possible to browse through many architectural books without encountering this term even once.” It seems, Sagmeister continues, that designers tend to deal less with form, because most of the time they are busy thinking about an attractive concept or trying to solve problems related to functionality. But in his eyes, beauty = function: beautiful things were seemingly created only to impress. The peacock’s feathers do not allow it to fly or make it easier for it to walk, but give it an evolutionary advantage – the ability to win over the female peacock. In other words, beauty has the power to change reality, to influence the mood, daily function, and the quality of communication that exists between us. In fact, in this sense it is no different than the mouse component that helps to operate the computer or a parasol that protects us from the sun.

So why did we start thinking mainly about function and less about beauty? Sagmeister chooses to blame his “Austrian colleague”, the architect Adolf Loos, who lived during the 19th century. This was a period when Austria displayed its power through monumental architecture inspired by different periods such as the Renaissance, the Gothic period and Classical Greece. In Loos’s book Ornament and Crime, which was of great importance to the Bauhaus movement, Loos argued that the more ornaments works have, the faster they go out of style and their value declines. It is no accident that Sagmeister chooses to accompany his statement with pictures of modern, unembellished buildings from World War II, among them Auschwitz barracks designed by the Bauhaus graduate, the architect Fritz Ertl, thus, leaving his listeners to think about whether the ornament should be blamed for crime.

Sagmeister also chooses deploy God in his struggle against monastic modernism, for “God is not a modernist,” as verse 31 of Exodus 25 proves, there God asks Moses to create an ornate candelabra: “Make a lampstand of pure gold. Hammer out its base and shaft, and make its flowerlike cups, buds and blossoms of one piece with them” or in Sagmeister’s words: “a non-modern light fixture”.

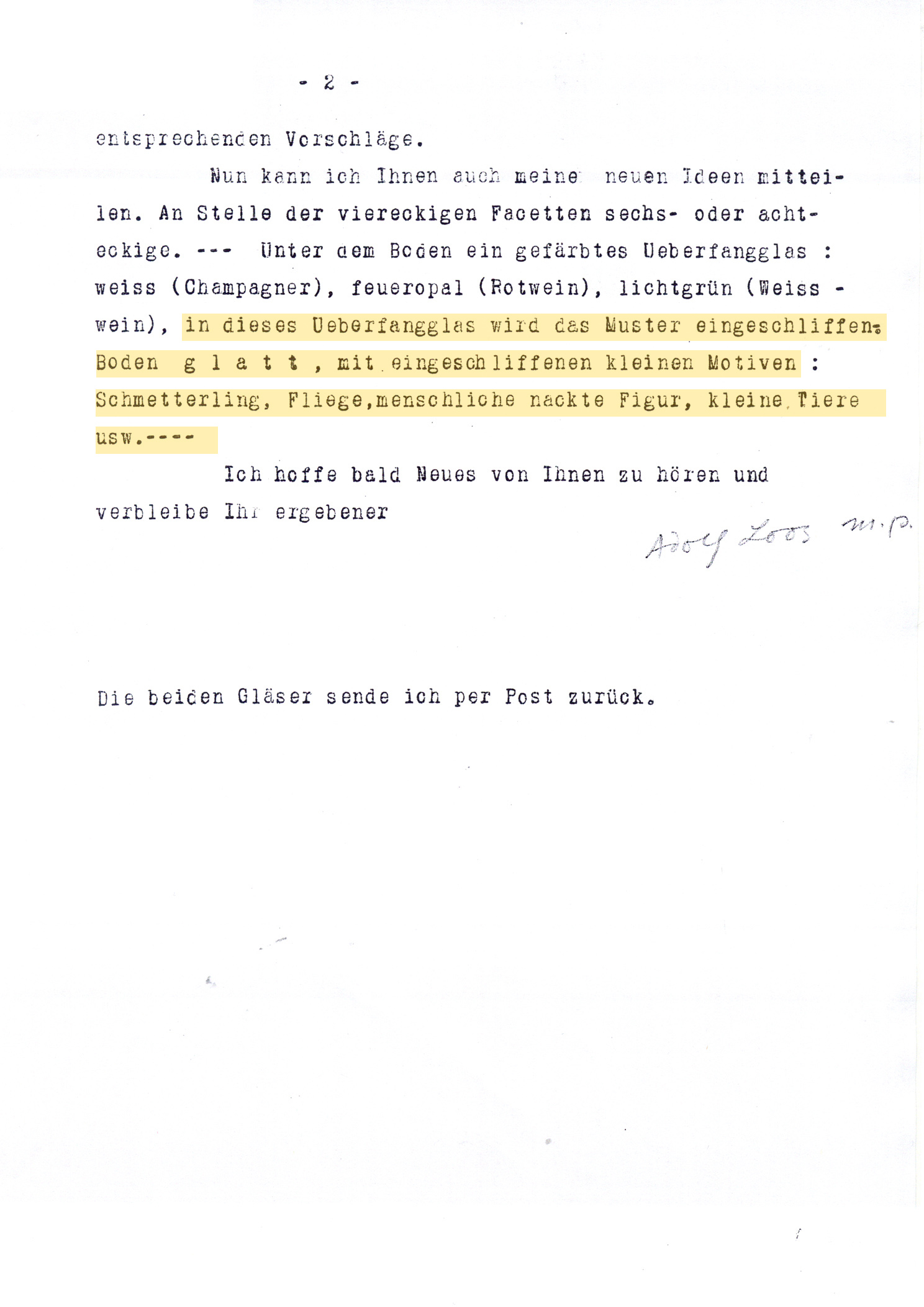

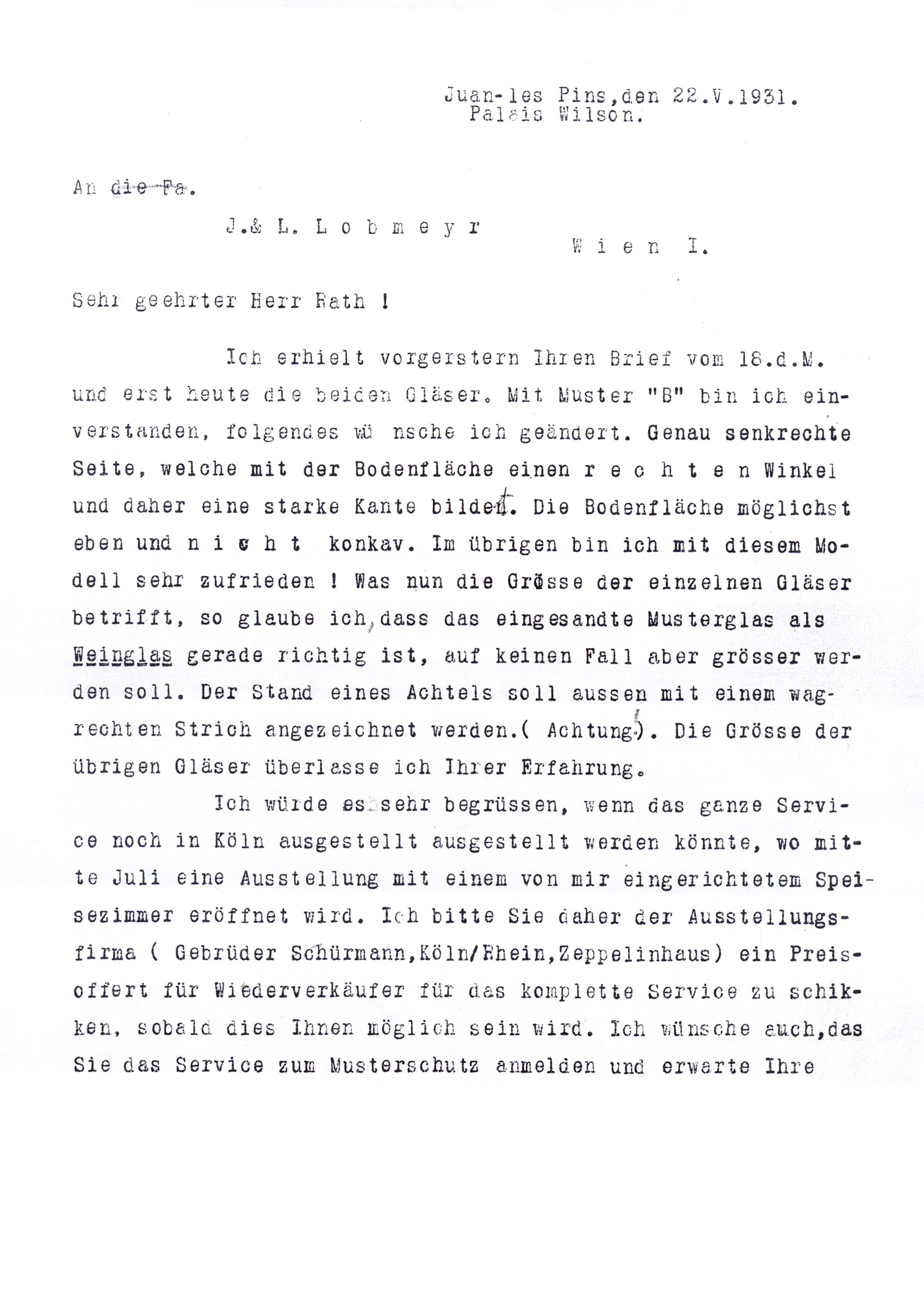

To remain with the terminology that originated from the world of faith, Sagmeister claims that even Adolf Loos eventually saw the light. In the 1930s Loos was a designer for an Austrian company called LOBMEYR, and created a series of glass cups based on hand-crafted geometric glass shapes. In a letter he wrote to the company at the end of the project, he confessed: “I can also see in a later date small ornaments put on my glasses things like the human figure, butterflies, small animal, and such…” Eighty years later, Sagmeister & Walsh realized Loos’s dream and created, a new set of glasses based on the original set, with surprising images of flies, breasts, a human heart, money and more at the bottom of each glass – images which represent one of the seven sins, or one of the seven virtues according to Christianity.

Adolf Loos’s letter : “I can also see in a later date small ornaments put on my glasses things like the human figure, butterflies, small animals…”

The final part of the lecture sheds light on the work of the partners, who combine commercial projects and personal projects. The studio is well known for offering its clients only one sketch during the design process. This method of work is unusual, since the standard design process includes a number of varied sketches that are narrowed down according to the customer’s wishes until the finished product is created.Sagmeister, as befitting for one who chooses to take on the role of the child in the story “The Emperor’s New Clothes,” argues that the reason designers tend to present a large number of options to the client is mainly the desire to impress with the amount of work that was done. And customers, on their side, feel that they have received a good return for their investment. “The commitment to one good option is more difficult, if we are wrong,” he elaborates” we use that direction as a platform to talk about everything that’s wrong.” But a withdrawal in the process usually occurs when the decision maker does not take part in the design process from start to finish.

Since the day of the lecture, the studio has published a book about beauty. In similar to the concept of happiness explored through the “Happy Exhibition”; the concept of beauty will also be at the center of an exhibition at the Museum of Applied Arts in Vienna.It is easy to get carried away by Sagmeister’s strong determination and charismatic character. But it seems that more than he teaches us about beauty, Sagmeister reminds us not to give up and to bring some of ourselves into any project, personal or commercial, because “in the end it is not a distinction between simplicity and complexity, or between a minimalist style and baroque. The question is if something is done sloppily or with a great love and care. “

The exhibition Sagmeister & Walsh: A Retrospective was displayed at the Design Museum Holon on the dates: June 06, 2018 – October 20, 2018