Club Silencio, a new members-only club, has recently opened in Paris. It was designed by renowned film director David Lynch and Raphael Navot, a young Israeli designer.

The exposure does not make Raphael Navot entirely comfortable. He plays his part, of course, talks about the process, volunteers a few more snippets of information about what preceded it, tries to help the people facing him to label and place him in the expansive field of ostensibly accurate definitions. In a world in which on more than one occasion young designers make blunt, bold, unequivocal statements in order to make an indelible mark on public consciousness, flood the web with information about themselves, ensuring it reaches its destination and is read, Raphael Navot looks like someone who is more interested in covering his tracks.

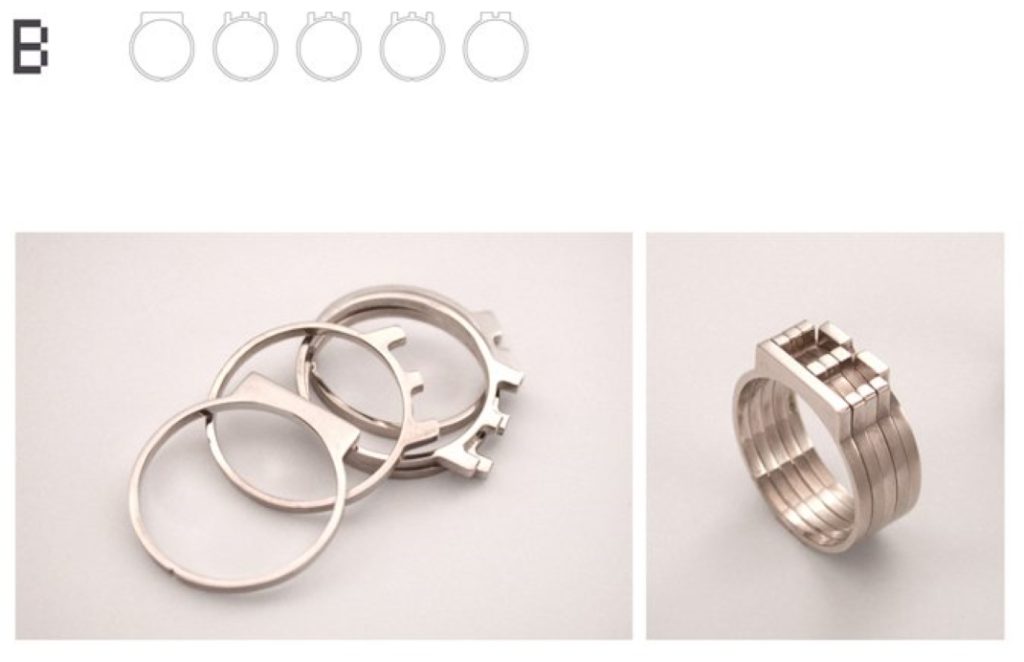

Until recently surfing the web yielded a handful of personal interviews (most of them to the Israeli press even though most of the time he does not live here) and an unmaintained website. And this despite the fact that his first project at Design Academy Eindhoven attracted so much interest that his teachers decided to fast-track him, and his graduation project Two Crowns featured on the cover of FRAME magazine and gave rise to a debate as to whether he can be defined as a designer.

After he graduated he began an internship in the Department of Human Behavior Research at Philips Design, and later joined Studio Li Edelkoort, where he served as assistant to Catharina van Eetvelde, the art director of View on Colour Magazine edited by Edelkoort.He does not think of himself a designer in accordance with the widely accepted semantics of the word, and certainly does not consider himself an industrial designer. According to Navot, studying at Eindhoven Design Academy, where “we weren’t taught how or what to design, but from where”, is what enabled him to develop his ability to move between different design spheres: interior design of commercial spaces (Tollman’s stores at Design Museum Holon and YOO Towers), architecture (a building on Hayarkon Street overlooking London Square), lighting fixtures, jewelry, and furniture.

“It was probably there [at the Academy] that I adopted the approach that research and study are the key to everything, and in my perception design is based on them and on the aspiration to understand the balance between form and function at its different levels, which can certainly include emotional aspects as well. Understanding this balance is, in my view, essential for the process, which at its culmination is supposed to ‘stitch’ the two components into a single entity, whether it’s a space or an object”, he says to Maya Orr in an interview for Bayit VeNoy magazine, and adds, “The designer is charged with responsibility. The design has to be responsible and reasoned, and integrity is the most important thing of all. With every piece I check myself over and over and include the client in order to create a dialogue that will ensure that these values are maintained”.

Navot makes a point of regularly visiting and working in Israel. We met him here when he showed his POH – Patchwork Oval Hemisphere at “Post Fossil: Excavating 21st Century Creation” in April and lectured during Israel Design Week in May.

“I discovered that wood from trees felled during a full moon is full of water and that it cracks in a much more interesting way”, he explained in his lecture about the process of working on POH. “I looked for natural wood, employed the principle of marquetry, an art dating back to the sixteenth century, and made it three-dimensional and random”. He found the wood he sought in Poland, and using a long patchwork process he created a kind of boat or bench, an object that casts doubt about its use.

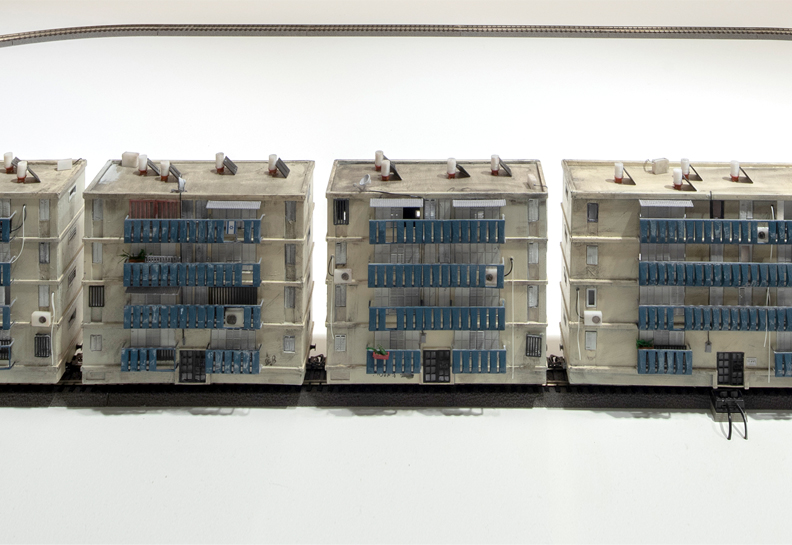

“A woman visiting Post Fossil said to me: ‘I really like this object, would it bother you if I used it as a stand for plant-pots?’ I welcome this. As opposed to the maxim ‘form follows function’, here function follows form. As far as I’m concerned people can turn this object into whatever they want”, he said. For the exhibition Navot created several prototypes, and he wasn’t even sure at the time that this object would make it to production. A few weeks later Julio Cappellini visited the exhibition and not surprisingly chose it to be manufactured by his company (click here to listen to Raphael Navot talking about the object). In “Talking Textiles”, an exhibition curated by Li Edelkoort in Milan (click here to read an article about the exhibition that was published in the Magazine) Navot showed a piece of furniture he designed together with film director David Lynch for Club Silencio in Paris. The members-only club occupies a 2,100-square-foot space that includes a 24-seat cinema, a live stage, a library, a restaurant, and private lounges. Situated at the mythical address that was once home to L’Aurore, famous for printing Emile Zola’s J’Accuse, the name of the club is a kind of tribute to the club in Mulholland Drive (Lynch, 2001), and aims to restore to Paris the glory it enjoyed in the 1920s. Together with Lynch, Navot also designed Black Birds, a series of black leather tables and seats.

“All the furniture is based on Lynch’s formal language”, he says in an interview with Yuval Sa’ar for Ha’aretz Gallery Supplement, “which like his cinematic language creates a kind of esoteric thinking… a chair isn’t quite a chair, and a table doesn’t always have four legs. And that’s the club: not entirely balanced”.The club, which recently opened in Paris, is defined as a members-only club for creative people, and most of us probably won’t get the chance to visit it, but if we type ‘Raphael Navot’ into any search engine, we will now get numerous hits.