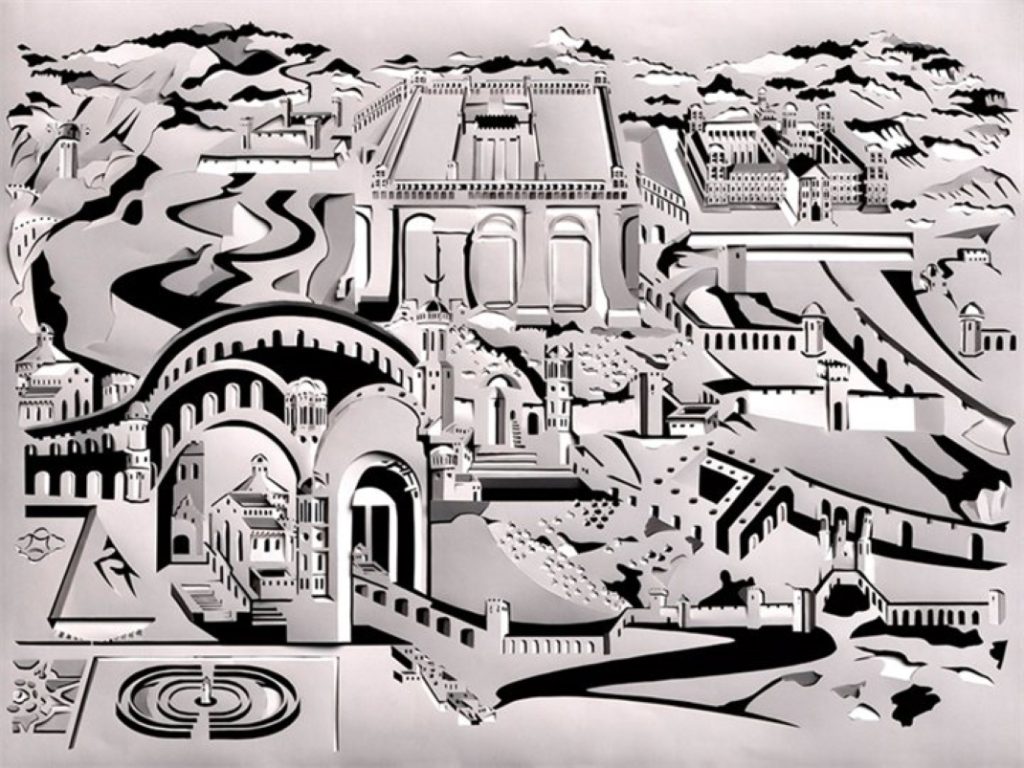

The external shadows of the Old City of Jerusalem emphasize the fact that the city is a single mysterious entity, casting its own shadows on themselves.

That Tuesday or Wednesday in 1867 was a warm day on which the final battle was being waged between the dying spring and the summer which began relentlessly pounding the Middle East. That day in the Holy Land the sun blazed with particular fastidiousness. A man dressed in black traveling in a carriage up the steep, winding road to Jerusalem, started shifting uneasily in his seat due to the blinding reflections of the sun on the carriage windows.

The man tried to look at the view through the windows. He thought that after the next hill the eternal city would come into view. But one hill was followed by another, one mountain chased another, and it seemed that this man – whose name was Mark Twain – was finally losing his patience.

Suddenly, on the horizon, Twain, his eyes blurry, saw the contours of Jerusalem for the first time: more than a city, it was a glittering “single mass” comprised of uniform, monochromatic grey buildings. A few fragments of iconic sites stood out (the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, the Tower of David, Damascus Gate) among numerous unidentifiable structures. “Not even one of our pilgrims wept”, Twain sees fit to note – perhaps due to the vast disparity between the beautiful, lyrical Jerusalem he carried within him and the dreary sight that unfolded before him. The impression Mark Twain describes resembles the feelings of American novelist and poet Herman Melville when he arrived in Jerusalem in 1857: “No country will more quickly dissipate romantic expectations than Palestine, particularly Jerusalem. To some the disappointment is heart-sickening. The color of the whole city is grey and looks at you like a cold grey eye in a cold old man – its strange aspect in the pale olive light of the morning”. And he continues: “So small a city pent in by lofty walls obstructing ventilation, postponing the morning and hasting the unwholesome twilight cannot be good for one’s health”.

However, it is not only Twain and Melville who felt depressed when they arrived in Jerusalem. Many pilgrims and visitors experienced disenchantment, and the most striking aspects are the neglect, the irritating light, and people who look like mice. In the Old City there is no air, no light, and the observer’s eye encounters an absence of architectural perspectives and interesting landscapes. From a different perspective, British pilgrim Kemper Fullerton arrives in Jerusalem in 1918 and writes: “The first appearance of the city as we rode from the station in the fading light of the late afternoon was distinctly uninviting. It looked dusty and haggard after the summer heat”.

Mark Twain thinks that Jerusalem is better in paintings, in art, because in the creative world light and shadow, perspective and color, architecture and nature can all be planned in accordance with one’s taste. Consequently, many pilgrims and visitors had doubts about the monotonous, ugly corporeal Jerusalem they saw, which undermined the city of their dreams.

Back to Mark Twain. In 1867 the Jerusalem noon shadows are absorbed by the churches, the buildings, the streets, the donkeys standing near Jaffa Gate, as though all the gods had fled, leaving the city lifeless. Twain and his entourage of pilgrims probably looked at one another and discovered that they too did not cast shadows on the ground, as though they were dead, due to the disappearance of shadows at that time of day in Jerusalem.

The hours go by, the pilgrims leave their belongings in their boarding house, and go outside. Now the sun is striking the Old City at an angle; heavy shadows cover the ground, and press Jerusalem’s primitive architecture into the brown earth. The sight reinforces Twain’s first impressions as he approached the Holy City: Jerusalem, the Old City, looks like a single entity with one big external shadow darkening the primarily empty area surrounding it. Estates are visible here and there outside the city, the odd building outside the city walls, a shadowy tail emerging from Jaffa Gate in the form of a commercial street, and not much more.

The external shadows of the Old City of Jerusalem emphasize the fact that the city is a single mysterious entity, and within it the foul-smelling, anonymous houses, coupled with the city’s narrow streets, cast their own shadows on themselves. The Old City’s self-shadow blurs the city’s inner character, creating a cheerless, labyrinthine, and especially a dark atmosphere.

One would assume that the Old City of Jerusalem, small and labyrinthine from the inside, which looks like a single entity from the outside, casting a uniform shadow over an empty, hilly area, could have presented an impressive spectacle for pilgrims and visitors. Yet Mark Twain spoils this assumption. Why? Because Jerusalem is so small, “…no larger than an American village of four thousand inhabitants… A fast walker could go outside the walls of Jerusalem and walk entirely around the city in an hour. I do not know how else to make one understand how small it is”.

At the end of the day Mark Twain and his companions return exhausted to their boarding house. On top of it all, they have been completely burned by the sun. They have had their fill of beggars, swindlers, of the dirt and squalor of Jerusalem, of the grey that dominates the landscape. Better to remain where they are and not go out. In the end, Twain muses, the magic of the corporeal Jerusalem can be recreated once time has erased the disturbing experiences; when time restores to Jerusalem something of its mystical, romantic power: perhaps magic that originates in imagination.

In 1918, British architect and leader of the Arts and Crafts Movement in England Charles Robert Ashbee arrived in Jerusalem. He had been invited by the city’s first military governor, Sir Ronald Storrs. Ashbee was appointed civic adviser to the British Mandate of Palestine, and later became secretary of the city’s planning committee and the Pro-Jerusalem Society. By means of these two positions, Ashbee began to engage in rebuilding the city.

Since Jerusalem was a tiny, dark, and ugly city, it should come as no surprise that in the followingdecades the city’s planning policies were not based on the characteristics of the corporeal Jerusalem or its actual needs, but rather on Mark Twain’s intuitive feelings: Jerusalem’s charm would be born once reality is built on its imagined characteristics. In his writings Ashbee mentions French novelist Pierre Loti who held that Jerusalem is the first of all “cities of consciousness” – an artificial invention of Western consciousness. Thus, Ashbee does not endeavor to plan Jerusalem in accordance with pragmatic urban projects, but paradoxically, by constructing an assemblage of mental images that would accord Jerusalem a new aesthetic, color, desired light and shadow, and its own architecture.

Did Ashbee succeed? Did his Israeli successors successfully change Jerusalem’s shadow? The urban fabric of the Holy City has remained torn, cracked, and fragmented. Urban planning was not a priority of the planners, British and Israeli alike. But did they succeed in building for us an imaginary, illusory, and beautiful Jerusalem? Who knows? It is all in the taste of the beholder.

All photos in this article are courtesy of Ofer Manor, Chief Architect of Jerusalem as part of the Urban Shade Web .Platform