Every year, at the conclusion of Milan Design Week, journalists, curators and buyers, hurry to formulate the new trends in the design world.

Every year, at the conclusion of Milan Design Week (and recently even before its conclusion), journalists, curators, buyers, and other fortune tellers hurry to formulate the new trends and indicate clear directions toward which the world of design is steadily marching.

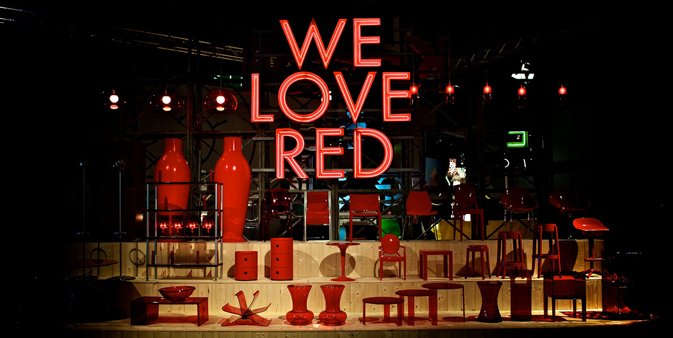

Forever YoungSalone del Mobile was established in 1961, during the prosperous years following the Second World War, by local furniture manufacturers who sought to equate the phrase “Made in Italy” with a mark of quality. In the exhibition’s first year there were 12,000 visitors, 328 exhibitors, and an exhibition space of 11,000 m2. Over the years the exhibition grew, as did the number of visitors, and the exhibition spaces expanded and were renovated, but the truly big change was how it spread and now virtually covers the entire city. This year COSMIT marked the fiftieth anniversary of Salone del Mobile and presented data according to which in comparison with the “handful” of exhibitors in 1961, this year saw 2,700 exhibitors showcasing their offerings on a 200,000 m2 exhibition space, and the number of visitors was in the region of 321,020. Although the data are still considerably lower than the record 383,793 visitors in 2008, just prior to the outbreak of the economic crisis, they are increasing each year.The long lines that form nowadays prior to the coveted opening events are without doubt testimony to the status of design in contemporary culture, but they echo an opening event from the past that was no less glamorous, and much more surprising: in 1981 the Memphis Group presented its debut exhibition in Milan. Thousands of people thronged the sidewalks leading to the venue. In an interview I conducted (in Ma’ariv’s “Signon” supplement, 2008) with architect Martine Bedin, one of the founders of the Memphis Group, she told me about their astonishment at the sight of thousands of people crowding the sidewalks all the way to the exhibition space. “It didn’t even cross our minds that it had anything to do with us. Sottsass (Ettore) said someone had probably planted a bomb there, because those were the days of the Red Brigades’ terrorist attacks in Italy”. The collection showcased by the group – cheerful, colorful, childish, pastel-colored furniture, and polka dot and stripe prints that were more reminiscent of the décor in a Las Vegas casino than anything else, and made use of a variety of inexpensive materials. They combined high and low culture, historical memory and pop culture, and drew inspiration from the popular world of the suburbs. Thus, with products that looked almost human and which violated the rules of good taste in design, members of the Memphis Group rose to star status virtually overnight (they themselves were captivated by the image they created and went to visit Graceland, Elvis Presley’s mansion in Tennessee).Perhaps it is no surprise, then, that it was Kartell’s booth that attracted the most attention at the exhibition this year. They celebrated the exhibition’s fiftieth anniversary with a Las Vegas-style carnival featuring alluring neon signs flashing messages such as “Try Me”, “Kartell Stars”, or “Just In Production”.But Kartell’s booth was the exception; most of the booths at the exhibition were designed with simplicity and restraint and were amazingly consistent with the atmosphere throughout the city and the economic mood.

Design for DownloadDroog Design from Holland could be counted on to accurately reflect new, as yet invisible moods that are true to a clear anti-star social worldview. Under the title “Design for Download” they presented a website that enables the consumer to custom design a piece of furniture for himself. In collaboration with EventArchitechtuur and Minale-Maeda they turned users into part of the design process. With their opening slogan, “Everything is makeable, anytime, anywhere, by anyone”, they have opened design to users, and created the building blocks from which the final product can be built. According to them, anyone who knows how to use a computer can use the program they have developed. Since the object is ultimately a composition, the consumer determines which object will be obtained (from a series of possibilities outlined by the designer, of course).

“Open design in the digital age”, says co-founder of Droog Design Renny Ramakers, “opens up many possibilities. It not only enables cost-effective transportation and storage, but also new approaches, and it develops creative tools, and online sales. It is founded on the fact that the 3D printer will bring about a revolution in the world of design. If the conjecture that there will be a 3D printer in every home in the near future goes on to become a reality, then ultimately Alvin Toffler’s dream will come true: customers will become producers”.