An interview with Shaul Cohen, one of the artists who made the Train House on view in the exhibition “Overdose”

The miniature models of “Train House” make the visitors at the exhibition “Overdose” feel like Gulliver in Lilliput. The book Gulliver’s Travels (1726), which may be enchanting and fascinating to children, was originally written as an allegory of British society. Train House also uses miniatures to express criticism: for the artists who made the work – Shaul Cohen, Avital Mizrahi, and Neil Nanner – the model of the building traveling in a circle, never reaching its destination, represents difficulties of housing in Israel and the rundown condition of residential buildings with their failed aesthetics and maintenance. We conversed with Industrial Designer Shaul Cohen about present reality as he sees it, on the difficulty of letting go of the models he makes, and about the micro and macro of his work process.

How did you begin designing miniatures?

In October 2019, I participated in an exhibition at the Berlin Museum (as part of Design Week Berlin) where I showed a piece depicting the differences between Israeli Bauhaus and German Bauhaus. This was the first time I attempted to build small objects that would be final models and not sketches.

Miniatures houses usually show a perfect world in miniature. What drew you to present the more worn out and damaged side of urban life?

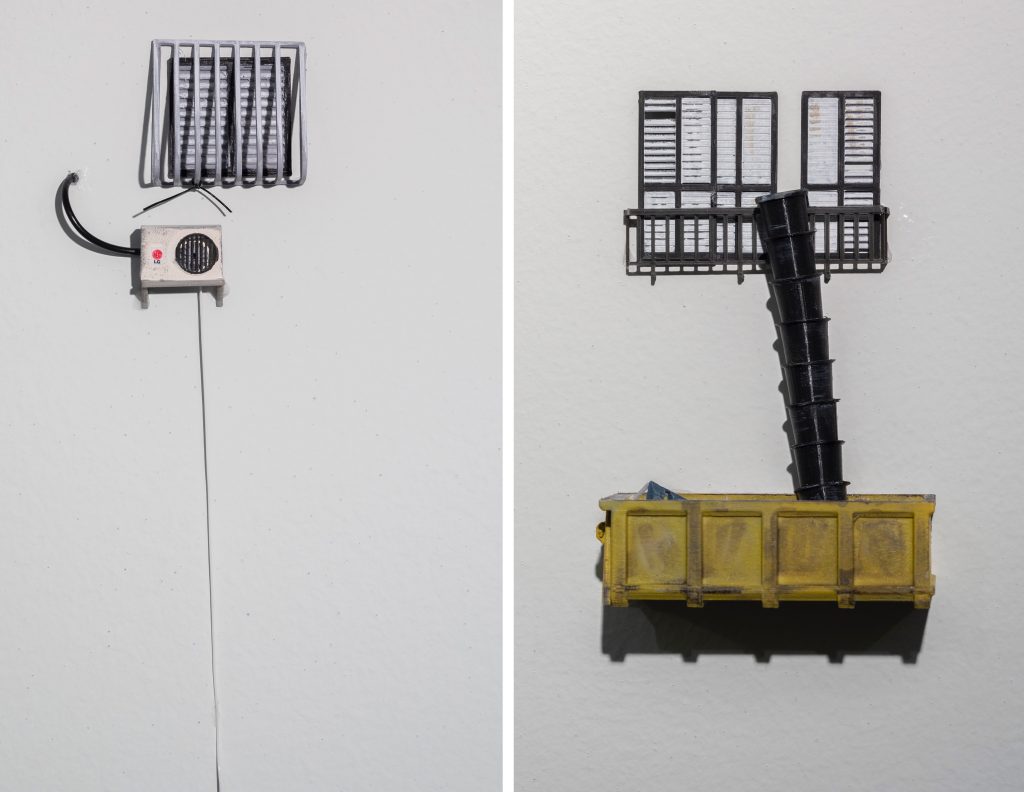

Yes, miniatures usually recreate an era or a perfect, clean scene. It’s not clear to me what attracts miniaturists in making such a false representation. I simply show reality as is, and never choose to make it cleaner or dirtier than the original – it’s easy for me to imagine the people who used to live in a building with stains or dirt on it, and apparently that’s why I’d always rather make a model of an old building instead of an alienated glass residential tower.

Can you share the work process with us, from initial idea to the last touch of paint?

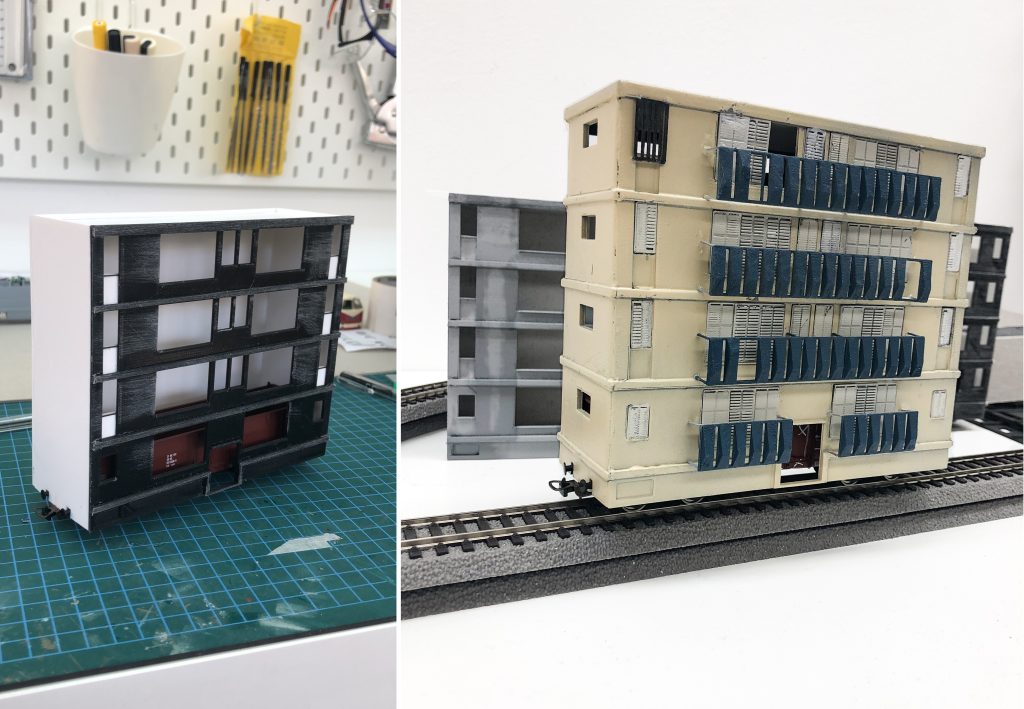

Stage 1 is information gathering. If the building is close by, I go out and photograph it myself. If it’s further away or no longer standing – I search for every scrap of information possible, blueprints on file with the municipality, or photos in a family album. The second stage comprises rapid sketches of all of the building facets to understand and see all of the details. If it’s a simple building, I build it from PVC foamboard cut with a mat knife; if it’s complex or has many details, I construct a digital 3-D model and print it out. I don’t use a specific scale because I’m not an architect, and don’t really know how to build to scale, so I calculate it by eye. I glue all of the pieces together, do a lot of sanding, use a basic undercoat of paint, and begin to “dirty it up” by brushing on acrylic paint.

Which buildings attracted you in particular during the work?

When I began to make miniatures, a simple building with interesting graffiti or a balcony loaded with plants was enough to make me imagine how it would look on a small scale, and I would put it on “my list.” Now, the buildings which fascinate me the most are the ones with the most moving story behind them.

Not only is your work very Israeli but specifically very “Tel Avivian.” Have you made models of buildings from any other cities or other countries?

Tel Aviv has very varied architecture, so it’s really a lot of fun, but to my delight, my studio “spread its wings” and I was able to build quite a lot of miniatures of buildings other cities. One of my favorite models is a building in Bnei Brak (18 HaRav Dangur Street), and recently many commissions from abroad have begun to arrive.

Isn’t it sometimes hard for you to part with the buildings you make?

I’ll say! There are many buildings with which I develop a close connection while working on them, so then I make another model to keep in the studio. It’s not necessarily an emotional connection, sometimes I just see that the model comes out more beautiful than I expected, and then I want one for me, too.

What’s the weirdest request you ever received?

I’m ready and waiting for strange requests! And, I’d be very happy if they would present me with a real challenge.

If you had unlimited time and budget, which building would you want to model?

I have a very long list of buildings I liked and would very much like to build a model of the “tin hall” – Ulam Hapahim [the May Day Arena nicknamed the “tin hall” for its roof, former home of Hapoel Holon basketball team] in Holon, where I grew up, or even my childhood home, but I am beginning to realize that I’ll never get to that list.

How did the concept arise for the Train House you exhibited in “Overdose”?

In the first Zoom conversation with exhibition curators Avihai Mizrahi and Neil Nanner, we came up with several ideas for various projects. Avihai brought up the idea of the play on words “railroad apartment building/train house” and that was the moment at which I stopped hearing anything else that was said as I began to imagine how the “train” would look.

The exhibition “Overdose” challenges the way we look at the ordinary day-to-day. Would you say that your piece also subverts our gaze at the Israeli architectural landscape?

Train House reflects a specific Israeli city scape, but we did try to put all of the relevant nuances into it that would simulate the model of a generic railroad building yet still give the feeling of a specific building.

How was it for you to work as part of a group?

It’s a first for me. Neil and Avihai have been working together for so many years and are so good together that I felt that working with them would feel like working with only one other person, but I very quickly realized that each has his own very sharp and different mind. I learned a great deal from this collaboration, and wish that we will have more opportunities to work together again in the future.

There is an innocence in using a toy train, but there is also something in the artwork that conveys melancholy. To what extent does the childlike playful element play a part in your creative work?

Of course I can’t argue with the viewer’s experience, but I had no intention of conveying melancholy. I think that it is precisely the play on words of Train House that’s very humorous, and an amusing way to look at Israeli daily life.

The railroad apartments are an architectural relic of Israel’s past During the 1950s and ‘60s they were a source of pride of a young, developing country absorbing massive waves of immigration. Now that they resonate the insult to the “Second Israel,” how should be view the model of these houses?

I don’t think that the railroad apartments are a disaster or an insult. I was raised in such a building in the Jesse Cohen neighborhood in Holon, and now live in a building in the same style in Ramat Aviv Hayeruka – these are two examples of two very different neighborhoods, but the architecture is absolutely identical. Every city has these railroad-style buildings, which is why it is very easy for viewers of the artwork to identify with it without feeling insulted. I even hope that it will arouse some sort of more nostalgic emotion.

The exhibition Overdose was displayed at the Design Museum Holon on the dates: 28 March 2022 – 30 July 2022