Materiality is fundamental to the creation of any object. It is the physical realization of an idea, directive, or solution; it is the moment something becomes “the thing itself.”

While rationalizing material choices pertaining to the creation of objects may seem pretty straightforward, with characteristics such as durability, cost, or sustainability taking the lead, there are many more material characteristics at play. A material’s native form is an often overlooked characteristic when observing products, probably due to industrial society’s ability to obtain any single material in various forms: fresh or dry pepper, coarse or fine ground pepper, pepper flakes, pepper paste or pepper spray. Since each material has its own identity, we may recognize that identity when observing a new object, or associate it with a familiar object made of the same material. Consequently, materiality can build bridges between new and familiar objects, thanks to the collective memory of a particular culture.

Materials also bring with them specific expectations. Applications that disrupt what we’ve become accustomed to expect of a material shed new light on what it is we want of it – and at times also on what we want of our objects. Objects are designed to tell stories, and these can sometimes contrast with, or be amplified by, the parallel story being told by their material makeup. Listen to them, and try to separate the voice of materiality from the background noises.

Peter Marigold, Split Boxes, 2007–2010

Peter Marigold’s wall-mounted box system owes its existence to the cut “logs” that comprise the corner connectors of each individual box. The materiality and form of wood logs are inseparable. The direction of the grain is the material characteristic that allows for lengthwise splitting, resulting in random angles whose sum is the circular circumference of a tree branch or trunk, and is equal to the sum of any box’s corner angles.The log lengths and split forms evoke firewood, thereby establishing an association with the domestic environment in certain cultures and with simple, rural craft.

Prehistoric Hand Axe

Flint was a common material choice for prehistoric hand axes, although other materials such as basalt, granite and even large mammalian bones were also used. It was likely chosen for its hardness, which may have seemed even harder when found in the form of nodules or a layer in a much softer bed of limestone. Yet alongside the characteristic of hardness, one must also consider the material’s availability, homogeneous structure and form. Flint, which has few mineral inclusions and is devoid of internal fractures, is relatively easy to work and control. A flint nodule of a certain size will “propose itself” to a knapper. It seems that an imaginary hand axe awaits below the surface, requiring only a few blows to remove the excess material and expose the desired tool.

Tal Gur, Kad Katan, 2004

Tal Gur’s vases are materially hybrid objects, composed of both plastic and aluminum foil. The vase is, technically speaking, made only of polyethylene, but the aluminum-foil mold used to create it has contributed its crumpled form as an inseparable part of the vase’s

material identity. The process of casting the plastic in the foil mold is a core aspect of the object’s existence (even more than its role as a life-support system for cut flowers). Due to the foil’s mechanical and material characteristics, each vase will have a shape of its own, within the geometric constraints set by Gur.

Airbags

Air is an often overlooked material in the design world: whereas architects treat air as a volume with a particular form that is trapped between walls, designers tend to see it, or rather not to see it, as an infinite expanse initiated where an object ends. Air contained in protective shells can be compressed by means of impact, while also providing thermal insulation. It is viewed as free, weightless and ecological – seemingly nonexistent in our awareness. Ever since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, air no longer appears innocent and is suddenly suspect, so that mail-order packages arriving from China were initially impounded or sent back.

Phillip Starck for Saba, Jim Nature Portable Television, 1994

Saba’s unmistakable Jim Nature Portable Television was released in 1994 as one of the high points in the evolution of TVs based on Cathode Ray Tube (CRT) technology. The unorthodox pairing of chipwood with gray plastic, which is characteristic of electronic appliances, was an aesthetically bold choice. But beyond the object’s visual appeal, the design paid homage to the history of CRT television sets, which were initially housed in a wooden box and treated as furniture.

The twist introduced by this television is the use of a culturally “low” material, which is commonly used for industrial applications, rather than a high-quality hard wood. It is possible that the inspiration for using chipwood stemmed from the visual “noise” of the wood particles, which echoes the static once seen on TV screens when the broadcasts ended at night.

Ami Drach and Dov Ganchrow, Bin Seats, “Stamps”, 2000

We are often conditioned to associate a frequently-encountered product with some of its material characteristics. A municipal garbage bin, for instance, seems to always be made of green plastic. The conscious choice of yellow plastic bins served to slightly shift the context of the works from the urban sphere to the gallery space. The garbage bins are made of a thermoplastic polymer, and can therefore be easily manipulated by heating and bending. The use of drilled perforation lines aided the designers in guiding and defining the bend.

Studio Khan (Mey and Boaz Kahn), Fragile Salt and Pepper Shaker – Work Model, 2008

Ceramic material is brittle. This material characteristic is often viewed as problematic, leading restorers to go to great lengths in order to piece together ceramic shards discovered in archaeological excavations. Boaz and Mey Kahn exploit the material’s fragile character in order to “activate” the product. Breaking a whole ceramic vessel births twin salt and pepper shakers, while including the consumer in the ritual creation of the product.

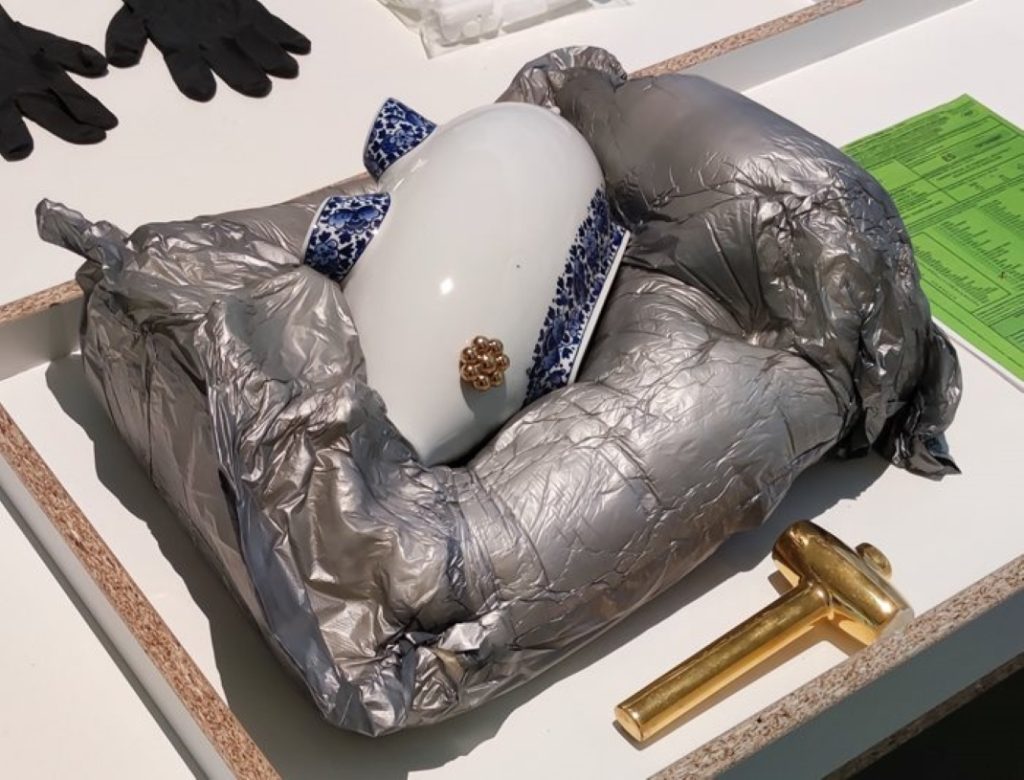

Sealed-Air Instapack-Quick (on-site polyurethane foam cushioning)

The real magic of polyurethane foam is not its efficiency in protecting packaged goods, but rather the surprising visible change it undergoes due to the chemical reaction created by the combination of two different components. This chemical reaction causes the material to foam up to more than ten times its original liquid volume, expanding and trapping air bubbles in the process. During its rapid expansion the Instapak bag fills the gaps between the storage box and the object nestled in it. When the material solidifies, it becomes a negative image of the object around which it expanded, perhaps even outliving the object itself.

Ami Drach and Dov Ganchrow, BC-AD, the Yellow Series, 2014

This work presents a readymade object, a replica of a prehistoric flint tool, which was repeatedly dipped in liquid elastomer until the plastic achieved the desired thickness. The application of this simple technique can be seen in the grips of familiar tools such as pliers or tongs. It increases shock absorption, friction in handling, and electrical insulation, while instantly branding the tool.

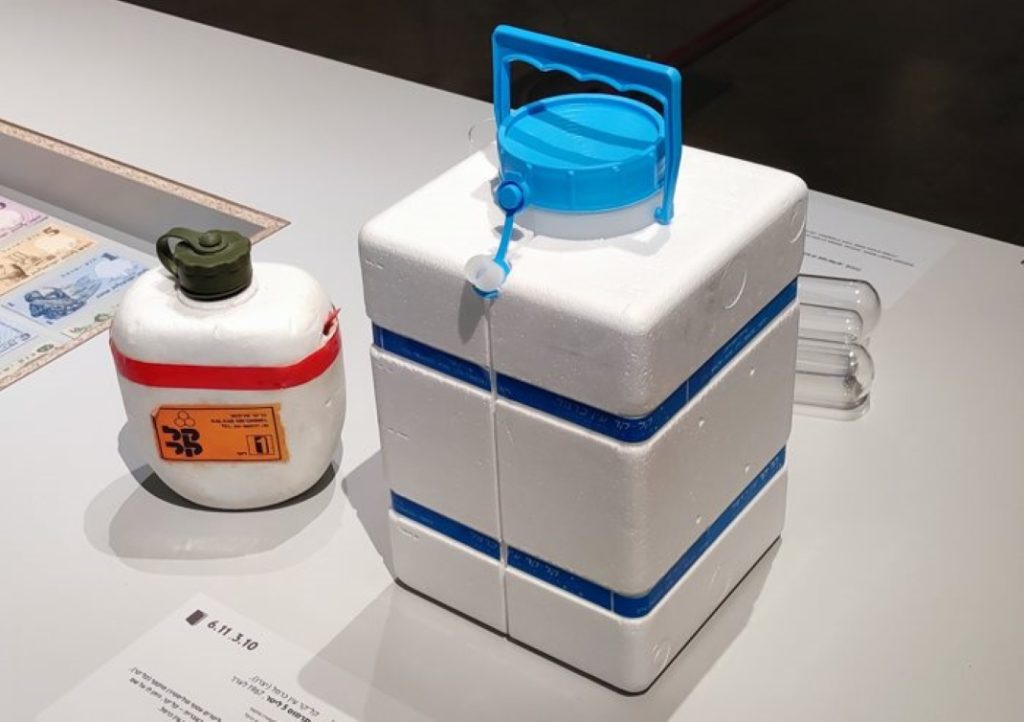

Kal-Kar Ein Carmel (manufacturer), Five-Liter Thermos, ca. 1967

This iconic water cooler is as simple as it looks: a plastic water bottle clad in a cube of Expanded Polystyrene (EPS). Strangely, the water bottle’s shape often does not conform to the cubicle exterior, making for a comical discovery the first time the EPS is removed – since it looks not unlike a dog after a haircut.

Cubes of EPS are a common sight in packages, especially ones of electronic appliances. They are usually designed to fit snugly in a cardboard shipping box, leaving us to question both the thermos’ form and its seemingly unfinished appearance.

EPS is composed of more than 95% air. This fact, in combination with its popularity (due to its low cost and other factors), has led to its widespread use and consequently also to its visible contamination of waterways, oceans and seashores. Today, one cannot help but see the irony of carrying potable water in a cube whose material makeup poses one of the biggest threats to clean water in nature.

Adital Ela, Criaterra, 2009

The term “composite materials” delivers an image of shiny, technologically advanced products such as drones or racing cars. Given these technological developments, it is easy to forget that humble

mud-straw composites have been used in construction and home environments for millennia.

Adital’s stools are composed of earth, and will return to it when they have completed their life cycle. Whereas chairs as cultural products have raised us from the earth, these stools enable us to sit on it while maintaining our current sitting etiquette. Coupled together, their form and materiality refer to rural mud stoves. The stool’s legs are really just a frame, evoking the openings for firewood and ventilation that are found in wood-burning stoves.

Gili Kutchick and Ran Amitai Studio for Stratasys, Design Inspiration Kit, 2020

Gili Kutchick and Ran Amitai’s Inspiration Kit, designed for Stratasys, includes a set of 3-D printed pebbles that showcase the technological abilities of the company’s printers. The material embodying these qualities is a photopolymer, which solidifies when printed with UV light. Light later also plays a key role in experiencing the pebbles through spectrums of different colors, varying opacities, and different reflections. These characteristics allow the material to take on numerous identities, and even to mimic other materials such as porcelain or wood.

The pebble’s form is based on the geometric form of a cube, which was seemingly reduced through a gradual mechanical process of abrasion —although in truth it has been formed by an additive technology.

Kevin Allouche, MYC – Growing Speaker, 2018

Mycelium is the vegetative part of a mushroom fungus, and acts as a biological binder when grown into an organic matrix of woodchip, hay, cornhusks or the like. It is environmentally friendly, and its ability to hold a predetermined form makes it a promising design front in applications ranging from packaging to architectural elements and coffins.

Kevin Allouche uses mycelium in a holistic process to produce loudspeakers traditionally made of wood. Beyond the acoustic properties of the material, its use here is related to research on mycelium as the forest’s communication system, where chemical signaling forms in what is called a Mycorrhizal Network – dubbed the “Wood Wide Web.”

Anat Golan, Exercises in Spoken Jewelry, 2019

This series of works plays on traditional technologies used in crafting jewelry, alongside the Hebrew terms used to describe them. Golan begins with the word kvisha (metal stamping), whose root is shared by the word kibush (occupation), relating to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The work consists of metal-stamped IDF military insignia that are compacted into a medallion, in a process that partially destroys/occupies them. The medallion, which is largely composed of brass, weighs down heavily on those who wear it.

Dov Ganchrow, V300, 2016

Plaster molds are the unsung heroes of the slip-cast ceramics production line, outputting tens or hundreds of products before they become ineffective and are decommissioned. Slip compacts on the interior walls of the plaster mold, through which the water is drawn, so that a solid ceramic wall slowly builds to form a cup, vase, and so forth.

Due in part to their limited lifespan, low cost and seemingly low value, plaster molds receive little attention, and only minimal investment is made in their production. Here they are treated by means of a highly functionalist approach, elevating them from a tool for making a product into a product in its own right.

—

Dov Ganchrow, product designer and Senior Lecturer in the Department of Industrial Design, Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design, Jerusalem

* Originally published as one of the itineraries in the exhibition “Black Box”.