As part of a series of articles on collections, Maya Dvash, the Museum’s Editor-in-Chief, met with Shira Shoval, Director of the Aharon Feiner Eden Materials Library, for a conversation about the Library’s role as a mediator between worlds, and about the significance of the materials collection.

________________________________________

At the Museum we are currently engaged in collections, and in fact view the entire coming year as “The Collection Year”: a book about chairs from the Museum Collection is due to be published very shortly, in the archive we are in the process of receiving the Gottex collection, and next winter the Museum will be showing an exhibition of eyewear based on the Claude Samuel Collection. How does the Materials Library fit in with this theme?

We’re talking about collections, and the collection of materials in the Library is part of the Museum Collection. But what makes the materials in the Library into a collection? And how are materials actually collected? The Materials Library is a snapshot of contemporary materials culture, of future trends, and due to the rapid pace of change – then inevitably of the past as well. A material that architects raved about several years ago can today be considered a marvel by a visitor outside the professional field. In addition to materials, the Library also engages in technologies, and in my view the truly new materials are often actually technologies.

There are more and more materials in the world every day, and we do not aspire to present them all, but endeavor to provide a broad survey and overall view of the world of contemporary materials. There are some to which an entire library could be devoted. For example, Formica, which is a vast area that updates at staggering speed, and we don’t have the ability or the desire to present every new Formica collection in the Library’s collection. We try to present only what is of interest to us in terms of technology, new context, or different application; and if a designer comes across a material from a particular series in our collection, we will always encourage them to go to the manufacturer and see the variety of different patterns. There are other materials libraries around the world that function as commercial entities and remove from their collection any materials that are no longer manufactured. We keep materials that in our view possess historical or educational value as well, even if they can no longer be obtained. In this regard, for example, we are more like the Museum Collection. In our mind’s eye materials possess great value in provoking questions for discussion, such as, why was the production of a particular material discontinued?

You don’t have materials that go out of circulation at all? The Museum Collection is space-dependent – the space needs to be enlarged in order to house more and more collections. How does it work in the Library?

Our collection is in small dimensions, and when we receive samples we ask that they do not exceed 20 or 30 cm. It’s clearly evident that there’s no uniformity in the material samples at the Library. In some libraries all the samples are of identical size, and they are systematically arranged on a wall or a uniform surface. In our library the materials are displayed in ordered chaos. And that’s intentional, to encourage creativity. So that visitors will come and in and want to touch and feel and draw inspiration and ideas. Obviously at some stage we’ll have to create an archive of materials, and possibly separate some of the materials. Although again, if our aim is learning, then it’s important to learn from historical materials as well.

Another interesting thing that’s happened in the Library in recent years is the collection of materials that are not industrially manufactured, but which were developed by designers and artists. That’s something else you don’t see in other libraries around the world, and this happens because the Library is part of the Design Museum, which naturally promotes an agenda that’s more educational. We don’t purchase materials or charge for displaying them. In this way we build a relationship of trust and objectivity between us and our “customers”.

The question is what actually makes a collection a collection in the Museum? Is a collection supposed to present a historical and cultural snapshot of the design world, and the items comprising it significant milestones in trends and thinking?

You can definitely see important cultural and design trends in the Library. They go together. Today, for example, there is extensive engagement in lightweight materials, and that’s associated with the era we’re living in. Cities are becoming increasingly crowded and there’s more and more high-rise construction, which has created a need to develop these kinds of materials, because the mass of materials needs to be reduced. More efforts are evident in the design academies’ graduate exhibitions, too, to produce foamed materials, and thus reduce their weight without impairing their properties.

How are the materials collected? Is it the Library that’s approached in most cases?

I wish ?. In fact, many of the commercial companies aren’t interested in displaying materials in the collection, especially international companies, because the market in Israel is very small. So we have to work harder than a library that’s located in Paris or New York. In many cases we approach the companies, which have no connection with design, and they don’t always understand the benefit they might gain from being associated with us. But there is definitely an increase in the number of Israeli industrial companies that approach us, and that’s part of a broader process that the Library and the Museum are undergoing together.

There are companies in Israel that are manufacturing sophisticated parts for aircraft or medical equipment using highly advanced technologies. There are amazing companies and factories that we go to that don’t know what design is or understand the value and importance of design. And maybe if they employed a designer, new and amazing things would happen there. There is still a lack of understanding that design can constitute a significant economic engine for industry.

It is important to us that the local public can be exposed to what’s happening around the world too, so we don’t display only Israeli materials or materials that are imported into Israel. However, we do want to support local projects and strengthen ties with Israeli industry. For example, we’ve started work on mapping studios and workshops in the Holon industrial zone, because fascinating things are definitely happening there right under our noses. What’s really interesting in this respect is adding materials to the Library’s collection that are not necessarily connected to the world of design. For instance, a company that manufactures agricultural netting; it’s an interesting example of a material intended for agricultural use, but an interior or industrial designer can also make clever use of this kind of material if he deciphers it correctly. And that’s an interesting local context because the most important industries in Israel are security and agriculture, in terms of material and technological innovations as well. If we can harness the creative public to work with materials from these worlds, then something interesting will happen.

One of the interesting aspects of the Library’s activities is the connection between worlds.

The Library has the ability and understanding to connect between foreign worlds. And within the world of design as well, which is a very broad and in which an interior designer may not understand materials that are very familiar to an industrial designer. In other words, even within the design world there are different publics and needs. If a jewelry designer comes across what is for her a new material in the Library, then it makes no difference to us if it’s a familiar material to architects for example. If she designs new jewelry from this “new” material, we consider it a big success for the Library. That’s something very special that happens in the Library: designers from all the different design fields, engineers, academics, and people from various industries all meet in one place. Industry coming into academia is rare, and it happened recently at a conference we held at the Holon Institute of Technology (HIT) following the “Smart Materials, Stupid Materials” exhibition. People from the local industries in Holon came who were not aware of this activity, and they were amazed. These are professionals who are unaccustomed to standing up and delivering lectures, but they possess a great deal of knowledge, and this constitutes an opportunity for them to share their knowledge and maybe even acquire new customers. And creators here are thirsty for this knowledge from industry. A situation is quite possible in Israel whereby a designer’s studio is located on the same street as some very interesting manufacturers and workshops, and the designer doesn’t even know about them.

These kinds of collaborations can also be seen in Jaime Hayon’s exhibition, which is currently showing at the Museum. They are always two-way collaborations that contribute both to the world of design and the factories. The importance of collaborations with designers needs to be clarified to the world of industry. This definitely requires work on the ground, and as more and more collaborations of this kind are successful, they will lead to even more collaborations. The revolution doesn’t happen in a single day. It trickles through.

That’s right. We need to create more collaborations of this kind here in Israel. I consider it a big success if a prominent designer comes to the Library to get ideas and draw inspiration. There are companies and workshops in our arsenal that are very interested in collaborating with veteran and prominent designers, but they have no idea how to go about it.

Well, let’s try to define what a new material is, and what a smart material is.

Okay, so there’s plenty of room here for the staff’s “curating” and discussions. What is a material? The basis is a table of elements that defines what the materials are, and then it could be said that what we have here in the Library are not materials but rather “products”. So the perception is very subjective. As a textile designer I have a particular perception of what a material is, whereas an architect will have a different perception. And engineers – with them you have to develop a common language. Experience has taught us that it’s all context- and observer-dependent. It depends on the knowledge, tools, and content world you come from. It’s never completely objective.

From an engineering perspective, a new material is a product or a chemical combination, and in other worlds these combinations are often only physical. And engineers can argue over the materials we define as new, and they’d be right! For example, translucent concrete, a revolutionary material that created a big buzz in the world, is not a new material from an engineering perspective. Because there’s concrete and there are optical fibers, and each of them still functions independently, but their combination creates a new surface that didn’t exist before. In the future I hope we’ll be able to include a materials engineer in the Library staff, and then we’ll be able to develop a truly new and interesting dialogue between the different fields, because in my view that’s where the future lies. Proof of this is Dr. Amit Zoran who participated in the HIT conference and represents the combination between a laboratory and a workshop.

At the design academies in Israel we see entire graduation projects engaging in a search for a new material, and even if they can’t be obtained as a raw material, it’s still interesting to include them in the collection. Because we’re part of the Museum Collection. Sometimes the collaborations come later through businesspeople and entrepreneurs. There are real-estate entrepreneurs who attend Library events because they’re really interested in the materials, and they incorporate a very high standard of design in their projects. They collect and research design themselves as a field of interest.

So, do you think the status of material in the world of design is changing?

It comes in kind of parallel waves. On the one hand the world is becoming digital, material and colors are becoming cleaner. But on the other, the materials in the digital world are crucial! Look at Nendo – everything is very white on the one hand, but on the other their engagement with material is significant because they’re looking for the emotion in material. It’s seemingly minimalistic, but the material is everything. The Museum’s inaugural exhibition, “The State of Things” (2010), featured a lighting element by Nendo, “Hanabi”, which is made from a smart metal called nitinol, a shape-memory alloy. This property enables movement of the metal by means of heat. Nendo managed to bring something poetic out of this metal that actually comes from the world of medicine. It’s like anti-material, but the material is crucial. It simulates nature. The question is what can the material do? Nendo recently created a series of candles whose color changes in accordance with the time of day, in accordance with the setting of the sun. Each color also has its own accompanying scent, signifying changing moods in the course of the day. Scent is also material. (Hanabi and the series of candles will be exhibited at Nendo’s solo exhibition, which is due to open at the Museum in June 2016).

It truly is material that connects to the new world and acts on all the senses. It is interactive, it changes, it performs several parallel actions. This is a new perception of material in that it is no longer a block of wood.

You might glance at the Nendo exhibition and think that it’s anti-material, but the opposite is true. It’s like language. Their minimal use of material is extremely precise. Nitinol is a cold, technological material, but in Nendo’s lamp it allows an imitation of nature and a human being’s breathing.

So in contrast, a block of wood is actually a stupid material?

A block of wood is liable to be perceived as a stupid material, but wood is one the most interesting and smart materials in the world. For example, in the “Smart Materials, Stupid Materials” exhibition (Vitrina Gallery, Holon Institute of Technology, closed on 11.02.16) we exhibited cork, which represents the opposite of nitinol, but it is a material that was created by nature and it’s one of the smartest. It is actually the impermeable bark of the Cork Oak. Cork Oaks grow in Spain and Portugal, and the bark protects the trees from weather damage and even fire damage since it is heat resistant. Cork is harvested by stripping it off the trees without felling them, since it grows back and can be harvested every ten years. It is also water resistant, it floats, and is lightweight. This is nature’s wisdom at work. In the exhibition we also presented an eggshell! It is a disposable packaging that protects life. What could be smarter than that? “Stupid Materials” is the title chosen by the exhibition curator, Shlomit Bauman, because there’s something defiant about it, and it provokes questions and interest.

That’s right, and the new technologies are often conceived from the smart materials and mechanisms in nature.

On top of that, the newest and smartest materials can’t even be displayed. They are produced in a laboratory and can’t be displayed as a raw material. For example, nanocellulose: we presented it at the exhibition as a kind of foam, but it’s a material that has many other forms and can be presented in many other ways. The truly new materials are not for use, no one yet knows what their applications are and what they’ll look like. Another example is aerogel – the most amazing material in the Library and there’s no way to display it! I tried, but as soon as it came into human contact, it shattered.

What does it look like?

Like a cloud. A cloud of material. Human beings have never seen anything like it before. It’s anti-material that can’t be captured and displayed. So in the meantime it’s sitting in a drawer. It’s the most lightweight solid material in the world that is ultimately a type of glass. It was developed for NASA as a material possessing excellent insulating properties, and its visual and sensory expression is cloud-like – 99% air!

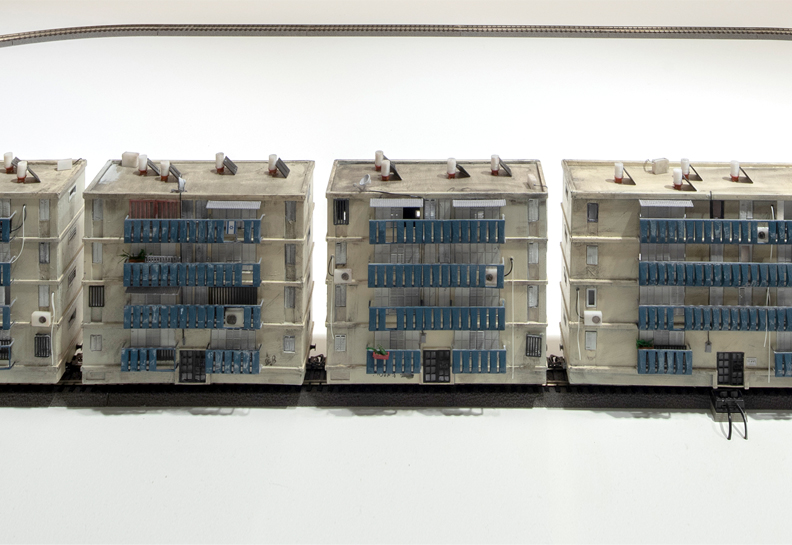

With some materials it’s impossible to understand their essence without touching them. For example, the “Senseware” exhibition which was mounted at the Museum in 2010 featured a chair by Shigeru Ban that looked like a “regular” chair, but only weighs 800 grams! And the fact that it can be lifted with just one finger is its genius.

And from here we can take it even a step further. As human beings we can examine this chair only if we lift it. But with nanotechnological materials, even if we pick them up and smell them we won’t be able to appreciate their properties because they are nano-engineered at a level that cannot be examined by any human criteria. But if, for example, a nanotechnological material is added to concrete, its weight can be reduced by 30%. In this instance, its appearance is meaningless.

![CcChair by Shigeru Ban, Senseware exhibition | Photograph: Shay Ben-Efraim]](https://www.dmh.org.il/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/shigero_1070-1-1024x826.jpg)

In many cases the most interesting materials don’t actually look at all interesting. And when people come into the Library it’s a bit like coming into a treasure trove, and we’re all naturally attracted to the shiny or sparkling materials, to those “precious stones”.

That’s right. And the most important things can’t even be displayed, they haven’t come out yet. What we see in the Library is already a bit dated. Because the world of design and architecture can make use of a new material only a very, very long time after it was developed.

How does the Library draw attention to the new materials? If it can’t be done publicly, it has no value.

New materials are constantly being added to the Library’s collection. Regular visitors to the Library are exposed to them, and there’s also a monthly newsletter in which we provide updates that’s sent to thousands of readers who are “materials geeks” like us. We recently launched a joint platform with the Museum where we introduce an interesting material every week. The materials are part of the Museum Collection, but we also realized that there are things here that could be of interest to a wider public. We try to choose interesting materials; some of them are new, but not always, because the Museum’s audience is not only a professional one. I’d be delighted if someone surfing the Museum website were to encounter a new material that gives them an idea.

How does getting to know new materials contribute to the general public?

Your question reminds me that a few years ago a group of high school students came to the Library, and one of the materials on display was raw wool fibers. A student asked me where wool comes from, and I was shocked. Once I’d calmed down, I thought to myself that actually, how is she supposed to know? She didn’t grow up around sheep and goats, and she’s never seen the material in its raw form before. So, to answer your question, understanding the materials around us is very important for the general public too. Because materials are everything. They’re a prism through which to see the world.

In conclusion, how would you characterize the kind of people who are interested, as you are, in materials?

We’re geeks. We all share the same quirk. At Library events you can see an actual community that comes regularly. These are the “scientists of the design world” who are interested in the way things work. They’re interested in defining a material by its properties. Some are professionals while others are simply inquisitive and do not necessarily have any design or engineering education, but this is really their main hobby.