How are values of change and development connected with bicycles? It is a known fact that the mode of transportation itself has remained virtually unchanged since it was invented in the nineteenth century, whereas the rider or cyclist undergoes processes of growth, change, and development from birth to old age. An entire set of different experiences develop around bicycles, and at each stage in life they seem to fulfill a unique and different need. The wheels are the child’s and adult’s alike, they express riding and self-propulsion, but they are also closely linked to the experience of riding in a group or more intimately as a couple, they are a means of getting from place to place, as well as for wandering around and enjoying open expanses.

A Bicycle has no Existence without a RiderA rider on his bicycle is in effect a hybrid body, half flesh and blood, and half metal, and the entirety of its essence is the connection between them for the purpose of generating movement. The ability to move forward is created by repetitive actions and when they stop, the bicycle’s right to exist vanishes too. This close man-machine connection can explain the mutual influence between them, in terms of man according the ‘machine’ attached to his body broad meanings, and a connection with the deeper layers of his soul.

A Different Cycling ExperienceThe act of cycling grants a new status to a place that is not a ‘place’: the space between the point of departure and the destination, where ‘life actually happens’. Moreover, when riding a bicycle all the senses are exposed to the environment: nature’s vivid colors, sounds and noises, smells, and the feeling of air on your face. In this way, cycling provides an opportunity to express and vent feelings and urges, and to examine boundaries and relationships with the world and society, which transcends ordinary modes of transportation. This unique experience, too, connects the bicycle with the rider’s more profound needs and his real life, which happens in the times between peak moments.

In this article I shall review our attitude to bicycles throughout our life, at way stations connected to our developmental stages as children and adolescents. Some of these stages recur and revisit us as adults in a kind of circular path. Reference to the developmental stages is grounded in the theory formulated by Edward L. Deci and Richard M. Ryan concerning the basic psychological needs for self-determination, and supported by leading development theories: Erik Erikson’s Stages of Psychosocial Development, and Jean Piaget’s Stages of Cognitive Development.

Competence, Autonomy, and RelatednessIn their book, published in 2002, Ryan and Deci defined three principal internal needs that are involved in self-determination, and which human beings require for their mental health and wellbeing:1. Competence – a sense of basic trust in the possibility of making things happen, and a sense of influencing the world around us.2. Autonomy – the need to drive life independently and act in harmony with one’s definition of self-identity.3. Relatedness – a sense of belonging to a group, and more intimate relationships with objects of love.

Analysis of the different needs met, and the experiences provided, by riding a bicycle, and understanding these needs through the prism of human development from infancy to adulthood, reveals very strong parallels and connections. Needs such as trust and influence, independence and identity, belonging and love, are filled directly by means of riding a bicycle. These subjects are represented in literature, cinema, and photography, and are manifested in social phenomena over the years.

Trust / Implicit Belief”The first demonstration of social trust in the baby is the ease of his feedings, the depth of his sleep, the relaxation of his bowels […] The general state of trust, furthermore, implies not only that one has learned to rely on the sameness and continuity of the outer providers, but also that one may trust oneself and the capacity of one’s own organs to cope with urges” (Erik. H. Erikson).

According to Erikson, building trust in the world and the environment occurs in the first months of human life. If the caregiver faithfully and lovingly responds to the baby’s needs, the baby experiences confidence in the environment and the world, by means of which he attains basic trust. With a correct blend of trust and mistrust the baby will attain the first psychological stage, namely hope – positive feelings concerning the future, and the possibility of coping with it.

The act of riding a bicycle disconnects the individual from the ground and his natural and usual connection with the world, and consequently upsets his sense of confidence. When riding a bicycle, as when swinging on a swing, he is in a state of hovering, no longer connected to the ground, and feels more like part of the air. This stage of disconnecting from the ground requires a high level of self-confidence and trust in the environment and in the bicycle to safely lead him from place to place.

A sense of confidence in the environment and the self is required in additional stages of riding a bicycle as well: in the process progressing from training wheels to independent riding, in the virtuosity adolescents want to display (riding with no hands, ‘wheelies’, and so forth), in urban cycling on busy streets, in riding on narrow dirt tracks, or for people who choose cycling as an extreme sport.

Influence / I Move, Therefore I Am “Everyone agrees in recognizing the existence of an intelligence before language. This intelligence, which is essentially practical, that is, aimed at getting results rather than stating truths, nevertheless succeeds in eventually solving numerous problems of action by constructing a complex system of action schemes and organizing reality in terms of spatio-temporal and causal structures […] These constructions are made with the sole support of perceptions and movements and thus by means of a sensory-motor coordination of actions” (Jean Piaget).

According to Piaget, an infant’s awareness is limited to what he knows by means of his senses and motor functions. Based on this knowledge and by interacting with the environment, the child actively constructs a system for understanding the world. The process begins in the first months of a baby’s life with action-reaction sequences, first when the baby discovers his body, and then the connection of his actions with external objects.

A bicycle is one of the first tools with which a young child is exposed to the connection between man and machine. The entire essence of a bicycle is the connection between man, his repetitive actions, and the resulting movement. A bicycle provides a basic understanding of the action-reaction mechanisms and the child’s direct influence on the desired result. By operating a bicycle, the child satisfies his basic need to directly and immediately influence the environment by means of his actions.

Independence / “On My Own” “Muscular maturation sets the stage for experimentation with two simultaneous sets of social modalities: holding on and letting go […] The infant must come to feel that the basic faith in existence […] will not be jeopardized by this about-face of his, this sudden violent wish to have a choice, to appropriate demandingly, and to eliminate stubbornly” (Erik H. Erikson).

In the first years of his life, the child accumulates experiences and insights which develop his ability to observe the world objectively and acknowledge the independent existence of people and objects. According to Erikson, from the second year of his life, the infant begins to undertake initial independent tasks (sphincter control, holding onto and letting go of objects in accordance with outer demands, and so forth). The main psychological need attained in this stage is achieving autonomy and ‘doing things on my own’.

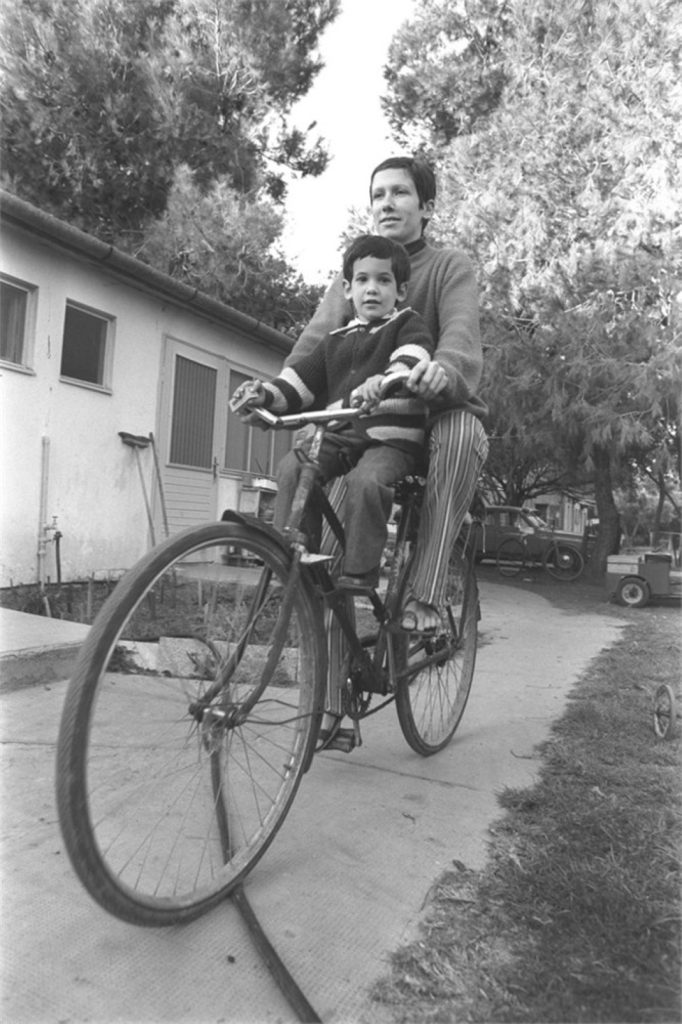

A bicycle is an object of defiant independence and hope. Already in childhood it is an expression of the aspiration to be independent, to get from place to place on your own, and discover expanses. Many childhood adventure stories incorporate bicycle riding as means for mobility, wandering around, embarking on adventures, and extending the territory controlled by the young person. As a mode of transportation, bicycles provide everybody with a convenient and inexpensive means of moving independently from place to place, up to a more advanced age when prolonged walking becomes physically difficult.

Identity / This Child is Me”In puberty and adolescence all samenesses and continuities relied on earlier are more or less questioned again […] The adolescent is newly concerned with how they appear to others as compared with what they feel they are […] The integration now taking place in the form of the ego identity is more than the sum of the childhood identifications” (Erik H. Erikson).

According to Erikson, in adolescence the young person asks the classic question: “Who am I?” and the answer does not have to be unequivocal. This is a ‘moratorium’ period for the adolescent to examine different identities and roles in order to emerge from it with a relatively consolidated personal, sexual, professional, and social identity. If the adolescent’s experience of self-determination is negative or unsatisfying, he is liable to suffer from role confusion and an inability to choose a clear and coherent identity.

A bicycle gives the child and the adolescent power. It enables him fast movement, physical superiority over the static or walking environment, and helps him to cope with changing situations. From a positive perspective, the child uses this power to develop a sense of maturity and responsibility. In The Famous Five series of children’s novels, bicycles help the group members to solve mysteries and extend help to their environment. From a negative perspective, the sense of power and the ability to flee the scene of the crime with relative speed also endows the bicycle with a significant role in the pranks and mischievous acts that frequently occur during childhood and youth.

References to mischievous behavior bordering on abuse appear in Forest Gump, where children torment Forest, whose legs are encased in metal braces and restrict his movement, and chase him on their bikes. In his distress, Forest starts running to his friend Jenny’s famous calls of: “Run, Forest, run!” until the braces fall apart and he manages to escape from the taunting boys.

Etgar Keret’s story Siren describes the theft and vandalizing of the school janitor’s bicycle by charismatic and successful students. Here too a bicycle is at the center of the weak-strong relationship, and the identity confusion between delinquent behavior and the characteristics of children from good families.

Relatedness / Tell Me Who Your Bike Is, And I’ll Tell You Who You Are”Relatedness refers to feeling connected with others and having a sense of belonging within one’s community” (Deci & Ryan).

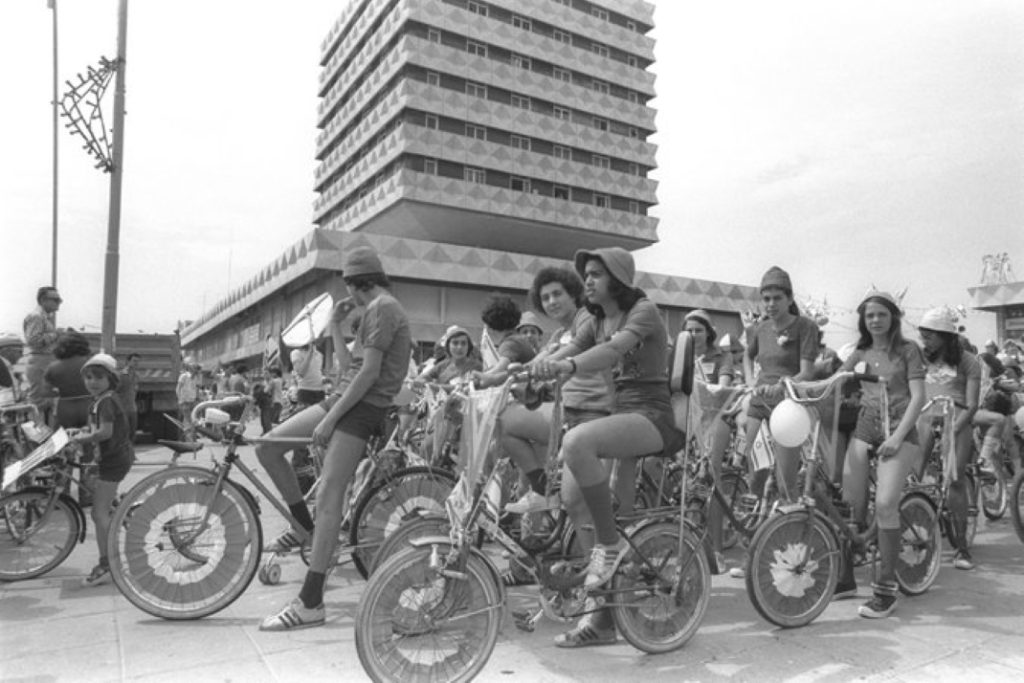

According to Deci and Ryan, the need for relatedness is a basic need. It is manifested in interactions with and belonging to a reference group, usually a peer age group with which mutual activities of communication and concern take place. This need exists concurrently with exploring and discovering personal identity, and the group occupies an important place in self-determination. According to Erikson, the peer group serves as a role model for the youth, a way of receiving feedback on his behavior so he can shape it accordingly.

The bicycle with its different characteristics has always served as a symbol of and testimony to the membership group. In adolescence the type of bike, the ‘model’, the ‘flash’, were all signs that attested to economic and social status. Thus, in On a Bicycle by Hanoch Marmari: “Mt. Carmel in those days was a safe area of complacent bourgeoisie […] Not only the cars were American […], the bicycles my friends rode were too. Refined, rounded metal tubes bearing exciting names like ‘Hercules’ or ‘Centurion’, in contrast with the blue Harash-Ofan, the laborer’s bike belatedly bought for me in installments. And above all of us hovered the children of the area’s well-to-do, riding on the ivory tires of the Rolls Royce of two-wheelers – metallic bottle-green English Raleigh bicycles bearing the gilded royal heron head badge”.

With the development of the sport of cycling, labeling has developed according to road or off-road cycling, and within the cycling group peer pressure is manifested in the type of bicycle purchased, investment in auxiliary gadgets, and even in the clothing that attends cycling.

Love and Intimacy / Like a Wheel within a Wheel “The young adult, emerging from the search for and insistence on identity, is eager and willing to fuse his identity with that of others. He is ready for intimacy […] To face the fear of ego loss in situations which call for self-abandon: in the solidarity of close affiliations, in experiences of inspiration by teachers and of intuition from the recesses of the self” (Erik H. Erikson).

According to Erikson, the need for a love relationship occurs from the age of nineteen onward, once the processes of adolescence have been completed, including self-identity formation and belonging to a reference group. The individual’s confidence in the self-identity he has formulated for himself has to be sufficient for him not to fear losing his self in an intimate relationship.

Bicycles frequently feature as a romantic motif in cinema and songs. The source of the romance associated with bicycles may be connected to the experience of riding together, side by side, at a pace that enables conversation and eye contact, in the open air that sharpens the senses, and in optimal conditions for intimacy and hope. This may simply be due to the structure of the bicycle: two wheels connected to create joint movement at a uniform pace, as in Ehud Manor’s song: “Like a wheel within a wheel / On a bicycle in autumn / Like a curl within a curl / Her heart in his arms”.

SummaryThe bicycle can be considered a mode of transportation, the sole function of which is to take us from place to place, however it is still romanticized and treated emotionally. In this article I have endeavored to show that the place occupied in our life by the bicycle does not necessarily stem from what it is, but rather from who we are, from the character-shaping processes we undergo. The bicycle at our side oftentimes helps, and at times it is merely a silent witness.

* This article was written as part of the MA Curating Program at Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design in collaboration with Design Museum Holon.