On the Refusal to be Called Witch | Ronit Elkabetz’s Extraordinary Women

“Magic is the belief that two separate bodies with no physical contact to each other can influence one another,” is the explanation provided by Zaza, who shares his bed with Yehudit, a character played by Ronit Elkabetz in Late Wedding (Dover Koshashvili, 2010). In retrospect this can be seen as a key moment in the cinematic and cultural universe created by Elkabetz. On and off the silver screen, her distinctly unique characters were fashioned within the semantic field of witchcraft. They seem to contain more than Elkabetz’s singular powers as actress, director and icon. With all due caution, one could in fact argue that the familiar, visceral figure of the witch, which has become bound up with Elkabetz’s persona, could act – in a pinch – to explain her power over Israeli viewers and the Israeli cultural field at large. And under the aegis of the label witch, which is signified ethnically, socially and along gendered lines, an other, who demands to be dealt with, can be signified. It facilitates the compartmentalization of desires and fears, and expressed in both her personality and an attention to the Elkabetzian visual phenomenon – from her flowing raven’s hair to her garb – in both her cinematic characters and her media appearances. In the public imagination, Elkabetz has been linked to the long tradition of the light-complexioned, flowing-locked witch, who in the West originated in two figures from Greek mythology representing horror and seduction: Medusa, representing beauty transformed in horror (memorable from her wild shock of snake-tresses in Caravaggio’s famous painting); and Lamia, the child-eating queen-demon. Thematic and visual elements of those stories – especially the hair and the eyes and their gaze – have continued to act as central motifs in the depiction of witches and their power.[1]

Elkabetz’s first thespian incarnation foreshadows her future roles. Oshra, her character in The Appointed [Hameyu’ad] (Daniel Wachsma, 1990), is a Lilith־type who can set fires with the power of her mind. We first see her in the audience of a magic show, the magician peering through the audience for a volunteer for his magic trick. A spotlight hits Elkabetz’s face and she responds to the magician with a real magic act. Like Zaza, the magician again commands her to come onstage, unaware that the roles have been reversed and he is now in fact under her spell. In the following scene, in the car, he asks her whether she is a magician and she silently smiles. Her fair face recurs throughout the movie, almost always in darkness or bathed in cold light, giving off a blinding sheen. In this role Elkabetz rejects not only the magician’s male authority but also the entire institution of rabbi and biblical patriarchs’ grave veneration, which is traditionally tied in Israeli culture to Moroccan identity. In an interview with her on the movie’s launch, the interviewer writes of Elkabetz: “there is something powerful, dramatic and inscrutable to her look. Sometimes she is sexless and even masculine, others she looks like a frightening witch.”[2] This description seeks to capture Elkabetz’s interiority, but remains a shell. She herself is adamant to go deeper inside still, to stubbornly ask questions combining religion and her family and focus on her own heritage: she came from a famous family of rabbis. Aware of her off-center and mysterious persona, Elkabetz makes a point-blank clarification: “there are no witches in Judaism,” she pointedly answers the writer’s voracious question.

In this text I look at some cinematic moments from Elkabetz’s work, analyzing them in light of the allusion to witchcraft and of Elkabetz’s renewed invocation of magic as a force־ field of personal and artistic work. Magic is embodied in a different way In each of these instances –explicit and implicit, thematically or visually – and its presence, so powerful just beneath the surface, powerfully charges the drama.

In Hanna Azoulay־Hasfari’s Sh’Chur (Shmuel Hasfari, 1994), Elkabetz’s character is an almost folkloristic representation on the cusp of Moroccan witchcraft and Western television, encapsulating the immigrating family’s vicissitudes. Out of the crisis the family is subjected to, television itself arises as a kind of visceral object taking on symbolic meanings of the West and Progress. Television is in fact the site that all seek to arrive at, as well as a foreign and menacing presence inside the home, corresponding to that other menacing presence in the family: Pnina, the eldest sister, played by Elkabetz. Though engaged in Sh’Chur – traditional Jewish-Moroccan folk magic – the women of the house are not witches. Pnina, on the other hand, is forced to embody a radical otherness: mental illness. While the women around her are engaged in the craft of magic, Pnina’s spell־casting is one of her very bodily skills, an ability ingrained in her physical body and the tortured soul trapped inside it. It is necessarily tied to the double world in which she operates – feminine and Moroccan – representing two layers: ethnic and gendered.

We learn about the layer of gender from Azoulay-Hasfari, who wrote the script and played the character if younger sister Cheli: “any power the women have in Sh’Chur they have because of witchcraft. The shift from Sh’Chur to [the movie] Shiva is another phase of their liberation.”[3] The attribution of black magic to women is part of an ancient libel familiar from both West and East: “because mostly women engage in witchcraft,” the Talmud says.[4] And several of Elkabetz’s characters in fact either explicitly deal in witchcraft or have magic powers. In her repertoire, explicit witchcraft is gradually sublimated into the depiction of inner powers not necessarily tied to external objects or the supernatural. The character of Vivianne Amsalem, who we will touch on below, transforms extroverted powers of witchcraft to dogged, world-order-changing, inner impulses.

On the ethnic level, Pnina’s character shoulders the prevailing cultural conception of the Moroccan community as implicated in witchcraft, an understanding that signifies the community of first- and second-generation Moroccan immigrants ambivalently: though trapped in submission to primeval forces, it also holds these powers, and its thus dangerous. This relation between the Moroccan immigrant community and the larger Jewish-Israeli host community is reproduced and expressed on the whole in the public’s relation to Elkabetz and her characters. The characters sublate the two faces of the received and shallow dichotomy between power and weakness. But furthermore, they simultaneously represent women on both ends of witchcraft – subjecting to its power and subjugated by it, spellbinding and spellbound.

“The influence of one object on another from a distance,” claims Zaza, is magic. “Stand there for a minute,” he orders her, motion after motion. She acquiesces, though defiantly. He is an object, she is an object, and between them is distance. “My beautiful believer,” he tells her condescendingly. Zaza’s words clarify the meaning but fail to illustrate it. It seems he is illustrating the fundaments of magic, but in fact he is demonstrating the scientific working of Gravity. Simultaneously is another magic is taking place: it is Yehudit who is the spellbinding element (“it is she who is fucking you,” his father tell him; “he’s poisoned,” says his mother). Yehudit prefers the assumption of faith, which is not inferior to the assumption of science. She burns a handkerchief soaked in his semen, repeating: “may your heart burn for me.” The spell fails, his heart burns with love but remains far from her, and this time no thanks to witchcraft but to her painful but sensible choice. She gives him up, refuses him. The binding of witchcraft and the mundane here is important – with the creation of Vivianne Amsalem, witchcraft will transform from script element to an even more obscure interpretive horizon.

The character of Vivianne Amsalem is the focus of a film trilogy created by brother and sister team Ronit and Shlomi Elkabetz (To Take a Wife [Ve’Lakhta Lehe Isha], 2004; Shiva, 2008; Gett: The Trial of Viviane Amsalem, 2014), and witchcraft can be a key to reading her. In Vivianne, Elkabetz has created a mind-body that, on the one hand, is subject to the institutional powers that be, and on the other emanates an almost supernatural presence, reaching out over the barriers of mere physical contact to force itself on a reality that had previously seemed preordained, fixed, regulated. A close reading of the character as it unfolds throughout the trilogy can deepen our understanding of her life’s course as depicted in short but very significant flashes. The start of this motion is in To Take a Wife, where we find Vivianne a subject of the structural violence of married life, at the hands of both her husband and the other men in her life; it continues with Shiva, where recently-separated Vivianne confronts the loss of her eldest brother within the claustrophobic cauldron of the Jewish mourning ritual; and culminates in Gett, where she arrives at her last stand, the very edge of liberty, pleading before the utmost Israeli social־religious gatekeeper: the Rabbinic court.

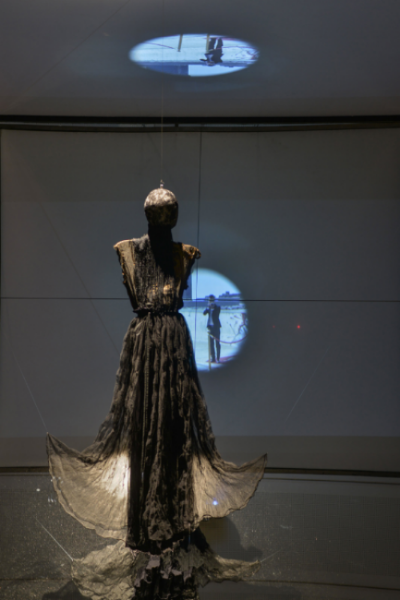

To Take a Wife opens with a sustained shot focusing on Vivianne’s face. In the background we hear the voices of her brothers, cajoling her and rebuking her for her desire for a divorce: “keep your head down,” says the voice of one of them while we gaze at her beleaguered young face, her tired eyes, the pallor of her skin against her dark hair. Towards the end of the trilogy, in Gett, we meet the same face from the same distance. Vivianne is speaking with her husband, Elisha. After tormenting her for years, he now relents to give her the longed־for Gett (a Jewish writ of divorce) in exchange for her promise to never be with another man. Vivianne’s face is fully lit, still pale. Still black and flowing, her hair is tidier, less disheveled. She is older. In the background are the Rabbinic Court’s greyish־white walls. “The political act was our very choice to film Ronit’s face and put it on the screen,” Shlomi Elkabetz has said, “to focus on her skin tone, the color of her hair, of her eyes, her silhouette, which is not an Ashkenazi silhouette.”[5]

Elkabetz’s iconic visual image cannot be separated from what has been termed her “acting style,” which has been described variously as unbridled, wild, emotional and hysterical, leading some to quasi־mystical interpretations of her behavior as ‘possessed.’ This is based on her different characters’ recurring gijdour: originally employed as a Jewish־Moroccan term for extroverted mourning practices at funerals – signifying, variously, the bereaved standing in a circle rhythmically chanting elegiac texts, sometimes culminating in face-scratching – it is used in the common Hebrew parlance of the present to signify dramatic, over־the־top emotional acts.[6] Shlomi Elkabetz has addressed the ‘possessed’ interpretation, which “assumes that the way Vivianne expresses her pain is not adequate, not ‘quality cinema.’”[7] Furthermore, he has refused to collaborate with the cataloguing of his sister’s physical, vocal and emotional gestures as an “acting style:” “does a wave breaking in a crash during a storm have an acting style? Or does it simply break, and I film it […] So why not the storm of a woman shattering? That is her essence.”[8] “Essence,” like spellbinding, captures a powerful inner core, but defies scientific distinction and the external sign, and eschews constraining value judgements.

The trilogy starts in the home and ends in an institution; opens with the longing to fulfill the desires of the heart – the desire to love – and ends with a fierce yearning for liberty, even at the cost of loneliness; begins with family and ends in bureaucracy. In the ending shot of Gett, Vivianne’s face is substituted for her feet, treading in plain flat espadrilles on the floor tiles ubiquitous in Israel – a visual emblem of Israeli space.

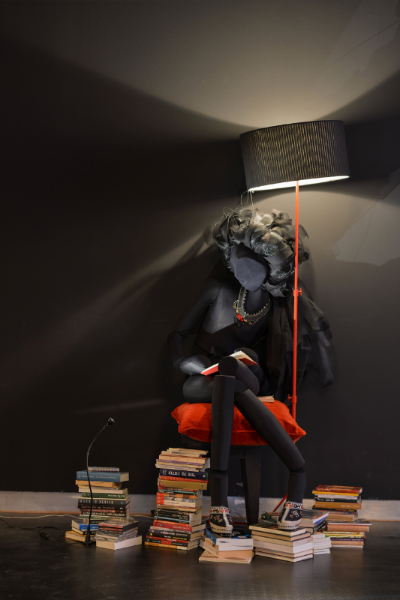

Is Vivianne Amsalem a witch? Like other unruly women accused of witchcraft throughout history, she too is a “stubborn and rebellious woman.”[9] Perched behind a black Formica school desk, Vivianne pleads with the judges of the Rabbinic Court for her liberty, the desk gradually taking on a stake־like quality: it is the place Vivianne is repeatedly backed into, shackled to, and tortured at. However a reading of Vivianne as just another metamorphosis of the actual witch – the one Elkabetz portrayed earlier in her career, in Sh’Chur – would be ignoring her characters’ complicated dissent. Theirs is a double refusal: they dissent to being labeled witches while also rejecting demands to shed their complexity, their sincerity and their powerful, unapologetic and irreducible presence. Elkabetz’s characters acquiesce to no test, and see no need to prove their magical powers. Their dogged dissent is performed through their consistent visiblizing of hidden identitational and cultural layers. The female figure portrayed by Elkabetz refuses to succumb to the witch figure’s familiar dictates, but as befits a real enchantress, allows the complex, contradictory and mysterious aspects of her personality to shine. These characters’ presence is expressed in their desires, but also in their compromises, pains and tribulations, when subject to familial, gendered and institutional violence. Their presence sheds light on violence that usually goes unseen. The typically transparent apparatuses of male and rabbinical violence are forced to confront the presence of an un־silent other.

In a 1997 interview with Ma’ariv, Elkabetz said: “I am not a witch like they try to portray me, though I do admit I have a certain eccentricity that goes into the roles I play.”[10] The label witch – which allows taking on the eccentricity that Elkabetz points to – simultaneously succeeds and fails. It succeeds because it allows us to tackle the unknown in a known idiom, to take on Elkabetz’s onscreen presence as well as the presence of real-life Elkabetz as artist, cultural figure, feminist and fashion icon. It fails because Elkabetz did not simply represent eccentric women on society’s fringes. While in films such as Or (My Treasure, Keren Yedaya, 2004) and Sh’Chur the characters she portrays are explicitly positioned on the edges of society and the family, the characters she portrayed in Late Wedding and the Vivianne Amsalem trilogy are in fact visibly familiar, long-haired feminine figures. They are sisters, mothers and wives, and we can recognize the streets they walk down, in their flip flops and dresses. They give their neighbor a haircut in their kitchen and wake their kids in the morning, hair upswept or unkempt. We know their clothes, their facial expressions, the cigarettes they smoke and all the trappings of their small Israeli apartments. A socializing impulse impels us to label single mothers, victims of abuse and prostitutes and as eccentric, to disregard any of their other characteristic besides these categories – and this impulse must be exposed and deconstructed. Elkabetz’s characters are ourselves. They are our mothers and aunts, our sisters and our partners. They cry out at the Rabbinic Court, fall silent when faced with domestic demands, refuse to acquiescence to the sword placed over their necks. They are “ordinary women” with extraordinary physical and emotional presence. The horror accompanying their externalization of their internal drama, their cries, heartaches and emotions is responsible for their signification as other – as witch. In the fullness of time, this horror is exposed as nothing more than a horror of the awesome forces women that women harbor.

————————-

Zohar Elmakias writes about visual culture and is pursuing a PhD at Columbia University Department of Anthropology

NOTES

[1] LORENZO LORENZI, WITCHES: EXPLORING THE ICONOGRAPHY OF THE SORCERESS AND ENCHANTRESS (FLORENCE: CENTRO DI, 2006), PAGES 7-77.

[2] ROGEL ALFER, “HANNAH AZOULAY HASFARI IN A MOROCCAN-ISRAELI CATCH 22 [HANNAH AZOULAY HASFARI BEMILKUD MAROKAI YISRAELI],” LAST MODIFIED OCTOBER 3, 2008, HTTP://WWW.NRG.CO.IL/ONLINE/47/ART1/794/959.HTML.

[3] ALFER, “HANNAH AZOULAY HASFARI”

[4] THE BABYLONIAN TALMUD (VILNA: THE WIDOW AND BROTHERS ROMM, 1880-1886), T. SANHEDRIN 67:1

[5] PABLO UTIN, CONVERSATIONS WITH ISRAELI FILMMAKERS (RAMAT HASHARON: ASIA PUBLISHERS, 2017), PP. 48-71.

[6] I THANK AHARON MAMAN, PROFESSOR EMERITUS AT HEBREW UNIVERSITY HEBREW LANGUAGE FACULTY AND THE VICE PRESIDENT OF THE ACADEMY OF HEBREW LANGUAGE, FOR THE ORIGINAL DEFINITION.

[7] UTIN, CONVERSATIONS, P. 70.

[8] IBID., P. 71.

[9] MACCABIT ABRAMSON, “BEAUTY AND THE BEAST IN CINEMA: VIVIANNE AMSALEM, PROTAGONIST OF RONIT AND SHLOMI ELKABETZ’S TRILOGY [MODEL NASHIYUT AHERET: ‘YAFA VEHAYA’ BAKOLNOA: VIVIANE AMSALEM, GIBORAT HATRILOGIA SHEL RONIT VESHLOMI ELKABETZ],” LAST MODIFIED JUNE 5, 2016, HTTP://SFF.SAPIR.AC.IL/2016/CSF.SAPIR.AC.IL/INDEX32E2.HTML?FILMS.

[10] YA’AKOV BAR-ON, “DARK GODDESS: BACK TO THE INTERVIEW CLARIFYING THE MYSTERY AROUND RONIT ELKABETZ [ELAH AFELA: HAZARA LAREAYON SHEMEFAZER ET HAMISTORIN HAOFEF ET RONIT ELKABETZ],” LAST MODIFIED APRIL 20, 2016, HTTP://WWW.MAARIV.CO.IL/CULTURE/MOVIES/ARTICLE-537632.