Twelve objects from the Design Museum collections, as well as objects used by the museum staff, were chosen by two conservation experts: Noa Cahaner McManus and Irit Lev Beyth. These objects offer visitors insight into the professional, practical and scientific aspects of museum conservation, as well as an understanding of the importance of responsible museum conservation practices.

Conservation experts are charged not only with preventing damage to cultural artifacts, but also with the technical and material study of artifacts and of their deterioration processes. Conservators must offer new approaches and solutions for conserving objects, based on the changing needs of museum displays and storage facilities.

The 12 chosen artifacts represent the following aspects of museum conservation practices:

-Types of materials and their historical, technological, ethical and scientific characteristics.

– Types of damage: aging, wear, and deterioration.

-The treatment of museum collections and objects to ensure their future existence.

-A theoretical concern with the use, accessibility and display of objects in museums.

Erez Nevi Pana, Recrystallizing, 2014

The use of salt as the main component of an object may lead to its degradation, as salt is a hygroscopic (moisture-absorbing) material. The display of such objects should be considered in relation to other humidity-sensitive objects. Relative humidity (RH) plays a critical role in the longevity of objects in a museum environment. High levels of humidity result in physical damage due to the expansion of organic materials, the activity of metals, and the development of dangerous mold. Objects are also damaged by low levels of RH. Repeated and extreme changes in RH, called “cycling,” are especially harmful to objects. In order to preserve their collections, museums regularly control and survey levels of relative humidity.

The presence of salts in archaeological artifacts stems from the environment in which they were buried. The salts move within the objects as levels of humidity vary, thus leading to their deterioration. The conservator’s role is to balance these environmental conditions, and sometimes even to de-salinate (actively remove salts from) the objects in order to stabilize them.

Stefan Sagmeister and Jessica Walsh, details from Beauty=Human, 2018

Insects thrive in the “dining room” called the museum, where they are drawn to materials such as paper, parchment, leather, feathers, fur, wood, wool and silk. They endanger the collections, and conservators are engaged in a constant struggle to eliminate their presence. Pest control in a museum environment must strike a delicate balance between periodical prevention and routine actions to stem the dangerous spread of insects. The use of hazardous pesticides has been significantly reduced, as monitoring and environmentally-friendly measures such as thermal fogging, freezing, and anoxia (the elimination of oxygen) have been proven highly successful and are now common practice.

Collecting and displaying dead insects has been part of the tradition of “curiosities” for centuries. It is important to remember, however, that many such objects, as well as taxidermy animals and ethnographic objects, were treated in the past with poisonous chemicals, and that conservators and other museum professionals must protect themselves from these potential dangers.

Lea Gottlieb, Gottex Bathing Suit, 1965

The invention of plastics in the mid-19th century gave rise to the technology of modern materials, which pose a significant challenge to conservators. The characteristics of these materials and their consequent deterioration are researched by conservations scientists, resulting in treatment innovations and improved storage. Bathing-suit manufacturers shifted from natural-based textiles to early synthetic materials such as Lycra, nylon, Spandex and polyester, and later to popular materials such as Neoprene and to cutting-edge and futuristic textiles. Deterioration manifested in hardening, stickiness, and oiliness of the early synthetics began to destroy important collections such as the Speedo collection. Today, cold storage is used to slow down the deterioration of these collections, and research in this area is in constant competition with the ongoing appearance of new and challenging materials.

Adi Stern and Shual Studio, Design Museum Holon Branding, 2010

A growing number of museum collections feature time-based media artifacts including sound art, performance art, and electronic media. The conservation of items in this category requires professional flexibility, and often privileges documentation over the “original” artifact. The museum logo/font belongs to this category, and its conservation thus takes into consideration its abstract character. The logo can exist in an electronic or physical format – printed in different sizes, on different supports, using different colors and printing materials – and may be reproduced at different times. A significant challenge concerning time-based art is to define whether the item must exist physically as a concrete object in the collection, or whether its electronic existence in a database is sufficient. This leads to the question of which components are most important to preserve. A specialization in the conservation of time-based art has become increasingly prevalent in recent years.

Vacuum Cleaner

A vacuum cleaner is an important part of conservation processes. Cleaning actions are accompanied by both practical and ethical concerns. Dust and dirt cause damage by attracting and capturing humidity, and bringing about friction, acidity, mold and pests. Vacuuming is often the first and preferred method of cleaning museum objects, since it can be delicately and carefully performed with a brush and a protective net, and the dust and dirt are gathered rather than dispersed. Nevertheless, cleaning processes are irreversible and “dirt matter” may be considered an important or meaningful component of an object. Conservators use special vacuum cleaners whose power can be controlled, and which are always equipped with HEPA filters.

Optivisor Magnifying Spectacles

Conservation processes always begin with a careful visual examination of the object, often using a magnifying apparatus: Optivisor magnifying spectacles, which enlarge the object to three, five or seven times its actual size, stereo-microscopes that magnify the object to 50 or more times its size, as well as advanced electronic microscopes. Magnifying technologies enable the conservator to analyze the object and its components, and to assess deterioration processes and the object’s current condition.

The Optivisor represents the critical role of observation at the examination stage, and later during conservation treatment. It is said that the greatest compliment to conservators is the invisibility of their labor. To this end, the Optivisor is an essential tool.

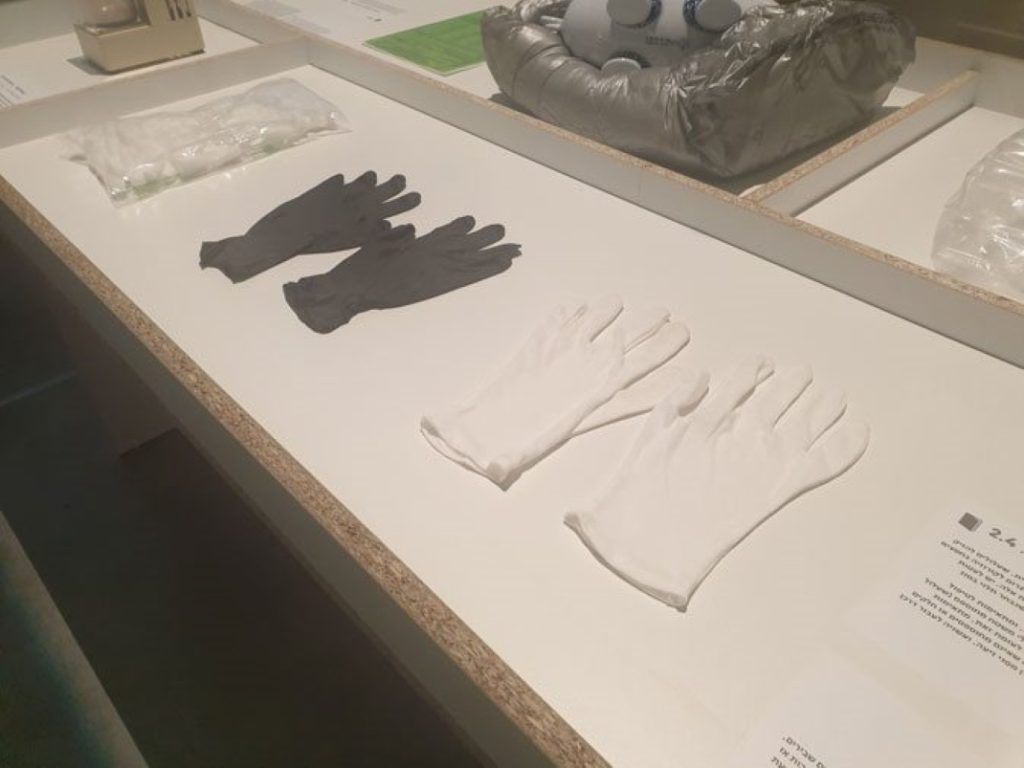

Cotton and Vinyl Gloves

Gloves protect objects from potentially harmful materials present on our hands, and also represent our respect and care for objects. Nevertheless, some materials can be damaged by the use of gloves. In these cases, the gloves decrease the sensitivity of our touch, and may cause tears and damage when handling old books, documents, and artworks on paper. Clean, dry hands are preferred in such cases. By contrast, exposed hands must not contact photographs or metal objects. Cotton gloves appear professional, yet the preferred gloves for handling objects are powder-free nitrile gloves, which also prevent slippage when handling museum objects. Needless to say, using dirty gloves defeats the purpose.

Whereas we usually aim to protect the objects from human touch, gloves are sometimes required to protect conservators and museum professionals in cases when the object has been contaminated by mold, is made of a poisonous material such as lead, or may be covered in harmful materials such as pesticides.

Rona Zinger, Model of the Lower Gallery for the Exhibition “Black Box,” 2020

Among museum objects are ones that were not intended by the artist to survive. Exhibition models are created for a temporary purpose, and are constructed out of cheap materials and through simple means, usually with no prior intention of entering a museum collection or being exhibited in the future. Nevertheless, these models may acquire importance and documentary/historical value, and as such will require conservation. The model represents the planning process of a museum exhibition, and indicates its complexity. Early on, the planning stage must take into account conservation-related concerns such as lighting, display cases, installation methods, the protection of exposed objects and more. The collaboration between curators, exhibition designers and conservators is essential to the success of the exhibition.

Talia Mukmel, Neo Stucco, 2018

Stucco is a combination of a binder, sand and water, and is used for casting, coating and architectural decoration. It is water sensitive and cracks due to the natural dehydration of the material, its location near doors and windows, or the building’s movement. Damaged stucco bends, bulges, becomes brittle, and finally collapses. Stucco conservation is performed by specialists in architectural conservation, a subfield that is developing parallel to the growing emphasis on preserving architectural heritage sites.

Talia Mukmel shifts stucco from its monumental architectural context, creating delicate, fragile works that reveal her careful study of the stucco creation process, much like a conservator studying production techniques and technologies. Her creations require safeguarding against over-handling and unnecessary movements, and challenge conservators due to their fragility.

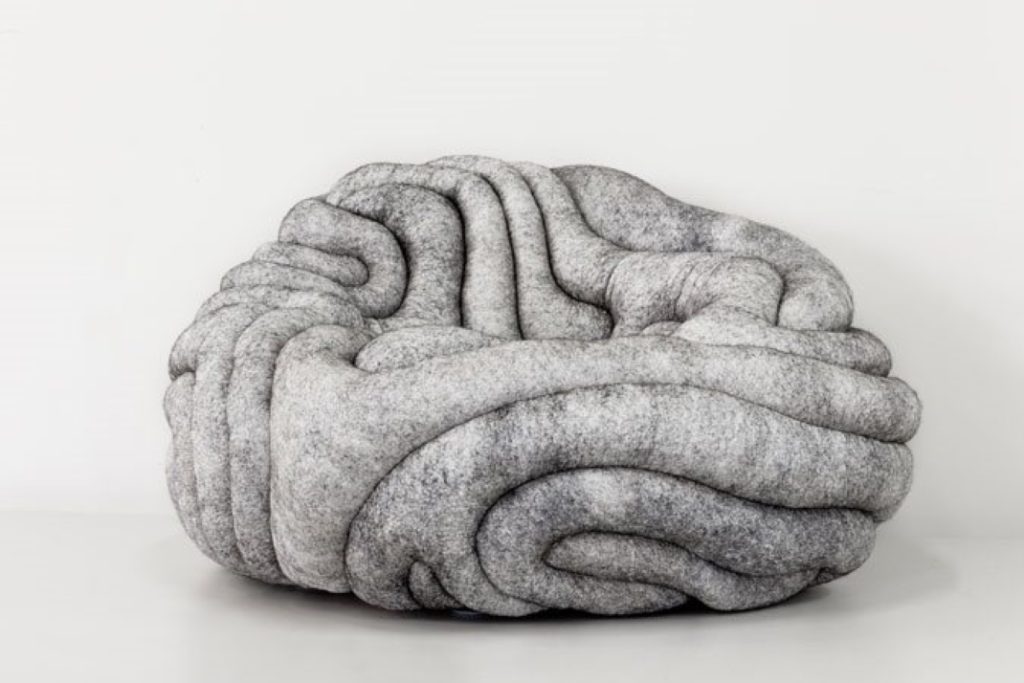

Ayala Serfaty, Primo Blanco, 2010

When included in museum displays, familiar everyday objects cause confusion due to the visitors’ sense of familiarity with them, and this may cause damage.

Often, it is possible for the same exhibition space to contain two similar design objects, such as Vitra chairs – one presented as a museum exhibit and the other for the use of visitors. Can visitors differentiate between the museums object and the functional, familiar object? After all, a chair is a chair is a chair, isn’t it?

For museum conservators, an object included in the museum collection ceases to exist as a familiar, everyday object and becomes a protected item subject to professional standards and ethical responsibility. Every object in a museum collection, regardless of whether it is a one-off or an industrially produced object, receives the same kind of professional attention. The responsibility of the conservators is to convey this philosophy to museum visitors, curators and exhibition designers.

Ayala Serfaty uses traditional materials such as wool and silk in the ancient technique of felting, combining them with the modern material polyurethane. Due to the combination of these materials, the conservator may expect the object to undergo complex deterioration processes, and will attempt to delay them by means of appropriate storage and display conditions.

Kenya Hara, Obuse-do Sake Bottle for Hakkin, 2000

This stainless-steel bottle bears a Japanese paper label produced according to a longstanding tradition. The use of this label in the design of a bottle for this ancient beverage is not surprising for those familiar with the heritage and important role of paper in Japanese culture. Traditional Japanese paper is produced in workshops that are considered living heritage sites, preserving the techniques and materials used by previous generations.

Three types of vegetal fibers – Kozo, Mitsumata, and Gampi – are used to craft the paper, and their different proportions and combinations produce a wide range of papers. Work techniques, materials and equipment such as brushes, knives, sieves and glues used by Japanese professionals have been adopted by conservators worldwide in order to treat museum objects.

Issey Miyake in collaboration with Reality Lab for Artemide, IN-EI “FUKUROU” Lamp, 2012

Museum displays require effective lighting in order for the viewers to understand the objects. Yet light rays cause museum objects to deteriorate, and must be limited. While UV rays are as destructive to objects as they are to human skin, the visible range of the light spectrum is also harmful and causes deterioration processes of various kinds. The impact of light rays on different materials is not uniform, leading to the establishment of standards for specific levels of exposure pertaining to different materials. It is the conservator’s job to instruct the museum staff about the safest display conditions for a given object by carefully choosing the type and strength of lighting, as well as the duration of the exposure.

This object is a lighting fixture, so that it paradoxically inflicts damage upon itself when on display. It is made of PET plastic, which is composed of recycled bottles and is considered “safe”, since it is a stable plastic and does not exude harmful organic compounds. This plastic is not expected to change or disintegrate due to chemical deterioration of its polymer chains. At the same time, one may assume that prolonged exposure to the light emanating from its own light bulb will gradually lead to irreversible damage.

—

Irit Lev Beyth, MA in object conservation, head of the metals and organic materials conservation lab at the Israel Museum, Jerusalem, and an independent conservator for museums and private collections.

Noa Cahaner McManus, MA in paper conservation, a specialist in the conservation and restoration of works on paper and archival items, and a conservation consultant to various collections.