Through the stories of a number of courageous, pioneering women, Yifat Hollander Amar examines the role played by bicycles as a means for women’s liberation.

In this article I seek to examine the role played by bicycles as a means for women’s liberation at the end of the nineteenth century. A review of social trends and processes, and the journeys of extraordinary women during this period reveals the complexity of women’s lives, the social proscriptions, restrictions, and codes with which they had to contend, and the role played by bicycles in this important social change.

Annie Cohen Kopchovsky: Selling Advertising Space on Her BodyAnnie Cohen Kopchovsky of Boston, a young wife and mother of three young children, left her family behind and embarked on a fifteen-month bicycle journey around the world on her own.

When she set out she dressed in conventional women’s clothes, but as her journey progressed she began wearing a men’s cycling outfit, and exchanged her woman’s bicycle for a man’s. During this period, she paid her way by publishing pictures of herself in remote villages as a unique attraction, sharing her experiences of her journey, and selling mobile advertising space on her body to The Londonderry Lithia Spring Water Company. It was 1894, and despite the worldwide struggle for equal civil rights for women, a woman traveling alone around the world was an extremely rare event. Due to her charisma and talent, Annie positioned herself as a myth, and even changed her name to ‘Annie Londonderry’ as part of her branding.

Dora Rinehart: Cycling with Strange MenAnother woman, Dora Rinehart of Colorado, gained a reputation as ‘America’s Greatest Cyclienne’, and was the only American champion female cyclist of her generation, engaging in long-distance cycling as early as 1896. Her records crossed borders, and she was perceived as a strong, determined woman who would let nothing stop her from cycling, even if it meant cycling unchaperoned with strange men who were not her relatives, which was unheard of at the time. Due to the need for comfortable cycling clothes she adopted a new style of divided skirt, and following her public statements on the need for this division in order to be able to pedal and cycle, these ‘trousers’ gained support among women, and the garment was even named after her, the ‘Rinehart Skirt’. Dora was one of the first women who also engaged in promoting products through cycling, and various brands were validated under her approval.

It was the end of the nineteenth century, a period of discovery, renewal, and the beginnings of new ideas. Three essentially different axes in history peaked during this period: the modernism movement, the buds of whose ideas were beginning to sprout and gain strength, the feminist movement that was growing and gaining strength in Europe and the United States – and concurrently with both movements, the status of the bicycle began to develop as a mode of transportation and leisure. The meeting points between these axes created an intriguing and unique space for a new era in women’s status to flourish and grow.

Modernism: Breaking the Old NormsThe second half of the nineteenth century is typified as the end of the Victorian Era, and as a period of discovery and craving for new inventions and technologies. The social changes that took place in the wake of the Industrial Revolution constituted fertile ground for dissemination of the modernism movement’s ideas, which proposed a reexamination of every aspect of existence: commerce, art, culture, philosophy, and so forth, with the aim of identifying the issues that prevented progress, and replacing them with new and better ways. The movement’s principles began filtering through to the general public, and legitimacy was accorded to breaking old norms to make room for new ideas.

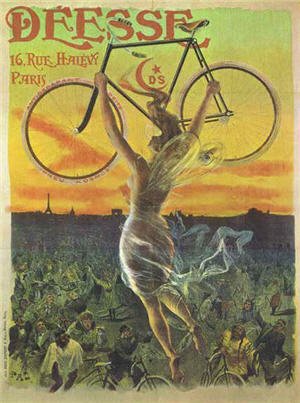

The bicycle was perceived as the most exciting and influential technological product of the period. It embodied modern ideas of technological innovation and design, and as such it constituted an intriguing development of a revolutionary and innovative method of transport, and quickly became a modern expression of freedom, speed, mobility, and independence. By means of the bicycle, local and spontaneous sojourns became adventurous, well-planned journeys; as an additional life skill, riding a bicycle became a potential for a career in professional cycling; and from a service vehicle, the bicycle became a social status symbol. At the end of the nineteenth century, bicycles influenced the lifestyle of millions of people around the world, including a great many women.

Feminism: The Bicycle as a ‘Freedom Machine for Women’Bicycles granted women the possibility of moving from place to place independently and without the need for various escorts, of embarking on journeys, and working and earning a living outside the home, and thus the boundaries of their world and occupations were considerably expanded. The independence of cycling granted women the possibility to discover the world, to explore, and to develop. This innovation contributed to the development of a trend of ‘new women’, a term used to describe modern women who went out to work, engaged in different professions and occupations apart from fulfilling their roles as wives and mothers, engaged with social, political, and other issues, and considered themselves men’s equals. These women also acted to attain equal rights for men and women. As bicycles became increasingly accessible, cheaper, and safer, the number of women who considered them a means for personal independence increased, and thus the bicycle became a symbol of feminism and new femininity, and was called a ‘freedom machine for women’ in Britain and the United States at the end of the nineteenth century.

Development of the Women’s Bicycle During this period, and concurrently with the development of modernist and feminist ideas, the realm of bicycles developed as well. Since the invention in 1818 of the ‘Draisienne’, which the rider moved by pushing it along with his feet, inventors and engineers have made various attempts to develop and improve the bicycle’s structure.

Numerous inventions contended with problems pertaining to steering, the frame, balance, and materials, and introduced changes to the bicycle’s structure and shape that were designed to improve it. They contributed to numerous improvements: from a pushbike without wheels, to the invention of a crankshaft that enabled the introduction of wooden wheels, the ‘penny-farthing’, which was also known as an ‘ordinary bicycle’, featuring a huge wooden front wheel, and a small rear wheel (due to its high seat and poor weight distribution, it was difficult and dangerous to ride). But a lot of problems still remained. With the development of the bicycle’s propulsion system, designers successfully changed the common structure of a big front wheel, and equalized the dimensions of the two wheels. This change improved stability, and resulted in a growing number of users. The most significant structural improvement was made in 1896 – in the frame, which included lowering the crossbar to make room for a skirt or dress, and using flexible tires that improved riding experience on rough tracks, and uphill and downhill cycling. This bicycle was called a ‘women’s bicycle’, and its popularity soared.

“Rational” Women’s Dress With the development of recreational cycling, a new need emerged: the need for unencumbered and unrestricted movement. The restricting clothes of the time, which included corsets, long, heavy, multilayered skirts worn over petticoats or hoops, and blouses with long sleeves and high collars, hindered freedom of movement, and symbolized the life of women up to 1890. These clothes inhibited even the smallest attempts at exercise or effort. The cycling craze granted virtually every woman the mandate to introduce change into her style of dress at a time when most women did not rebel against the dictates of fashion, and in a wide variety of women raised the issue of the complexity of their relationship with their clothes. Riding a bicycle required a more practical style of dress, and the rational dress movement introduced changes in fashion that were received with some consternation at the time. These changes angered many who considered it unladylike behavior that challenged the accepted norms whereby a woman had to be docile, modest, and maternal.

Bloomers Draw Ridicule and DerisionThe need for clothes that would enable comfortable cycling led to a number of creative clothing solutions. One was to thread a lace through the bottom part of the skirt or dress, which could be drawn up as required to stop the material billowing when cycling. Another solution was a skirt divided down the middle in the style of the ‘Rinehart Skirt’, which preserved the appearance of the long, heavy Victorian Era material. Some women adopted a masculine style of dress and rode in comfortable men’s suits, but due to the vehement reactions this attracted, they remained a small minority. Yet another solution was bloomers, a kind of combination between a skirt and trousers named after Amelia Jenks Bloomer, who dared to wear women’s trousers in public as early as the 1850s. Bloomers were a form of ankle-length undergarment that was gathered with elastic at the bottom. They were also worn by the first suffragettes who fought for equal rights for women at the end of the nineteenth century, and were met with ridicule and derision from society: although they enabled cycling, they were perceived as an act of defiance and licentiousness.

Is Physical Exercise Good For Women? The feminist struggle also raised awareness to concern for women’s health, and dissemination of the notion that control over one’s body would lead to control over one’s destiny. In light of this, the first woman on the UK Medical Register, Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell, who was also active in organizations that promoted women’s status and rights, claimed that physical exercise contributes to a woman’s robust, poised, active, and energetic body. She further contended that physical exercise would lead to women’s improved health, it would refine their bodies, and make their movements more graceful. The aim was to strengthen the female body so it would be healthier, more elegant and beautiful, and would withstand the role of procreating. This trend increased despite many and varied opinions holding that physical exercise in general and bicycle riding in particular were harmful to women: detractors enlisted a variety of arguments in efforts to deter women from partaking in cycling, and although it was a new form of exercise, many conservative doctors hastened to caution women against this sport which they viewed as dangerous to their health.

The female body’s fragility, delicateness, and vulnerability were a central argument. There was talk of the need to undergo medical examinations before cycling, and how one should cycle, eat, and drink, as well as the risks to skeletal and muscle structure. Less grounded ‘medical’ arguments warned that the stress and concentration of the woman endeavoring to learn how to ride a bicycle and avoid an accident would result in the creation of a ‘bicycle face’ – a permanent expression of anxiety, tension, and stress. They further claimed that women would develop a bodybuilder’s physique, suffer from headaches, depression, lack of appetite, and so forth. Another argument was that sudden death when cycling uphill, nervous breakdown, and loss of bladder control would be some of the risks for women who adopted this subversive activity.

The Bicycle as a Source of Sexual Stimulation Another issue that preoccupied the detractors was the fact that cycling could also be a source of sexual stimulation for women. It was customary to think that straddling a bicycle combined with the movement required to pedal and propel it would result in sexual arousal. Consequently, bicycle saddles began to appear with little or no padding in order to minimize friction with the saddle. The crossbar was straightened, and its angle changed in order to reduce the risk of female sexual stimulation by reducing the angle at which the woman cycled. Another argument was that riding on unpaved paths, and multiple jolting would also result in female stimulation, and consequently many tracks were repaired and adapted for appropriate cycling. It was also argued that the constant rubbing on the bicycle saddle would lead to grave moral damage and various venereal diseases, and would jeopardize the woman’s ability to bear children.

Competitions: A Source of Income for Women

Despite all these arguments, and fortunately for women, more progressive doctors identified the potential embodied in cycling, the possibility for healthy exercise in the fresh air, and encouraged it. Many women displayed considerable talent for competitive cycling that required a high level of effort and endurance. Women’s cycling began to develop as a competitive sport in Europe and the United States, and women took part in athletics competitions that often spread over several days. In those days it was not uncommon for women to compete against men as well. Extensive news coverage attended these competitions, and they attracted a lot of spectators, even more so than men’s competitions. The opportunity to see a woman’s body on the racing track, women cycling at high speed, and in general – a close-up view of women cycling – was intriguing, and these competitions constituted a respectable source of income for women who made a career out of them. One of the renowned female cyclists of the time was Louise Armaindo who was one of the first female competitive cyclists, and rode a penny-farthing with the big front wheel. She was considered an extraordinary and remarkable cyclist, competing against men and women alike. Frankie Nelson competed on a penny-farthing as well as an ordinary ‘safety bicycle’. Like Louise Armaindo, she competed against men and women, and was considered a ‘crack’ or ‘scorcher’ in the vernacular of the times.

SummaryIt can be said that bicycles played a significant role in changing women’s self-perception at the end of the nineteenth century, and in advancing social change by challenging traditional attitudes, beliefs, and values. Bicycles offered a unique opportunity for women that transcended geographic, economic, and social limitations. Women started seeing themselves as men’s equals, and with the independence provided by this mode of transportation they also dared to demand a change in attitude toward them, how they dressed, and their behavior. Without doubt, with the emergence of cycling as a women’s recreational and sporting activity began the official struggle for women’s rights.

* This article was written as part of the MA Curating Program at Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design in collaboration with Design Museum Holon.