Since its establishment in 1653, the Royal Delft factory has dominated blue porcelain earthenware production in Holland.

There’s something about ceramic and porcelain earthenware that affects me emotionally. Perhaps because the materials originate in nature, in the earth; perhaps because creating pottery and porcelain earthenware is an age-old craft; or perhaps it is the aesthetic effect of the decorated white porcelain with its perfect lustrous glaze that appeals to me.During Passover week I had the good fortune to visit the Royal Delft Museum in the first week of its new tour program entitled Royal Delft Experience. Illustrative and instructional aids, which have become increasingly widespread in the digital and multimedia age, are incorporated into the tours: it begins by stepping through a door and entering a ‘time machine’ in which visitors are acquainted with the history and origins of porcelain and how it first came to Holland and, of course, the renowned factory in Delft.

Another door opens to reveal a dramatization of the factory combined with multimedia films presenting all who take part in the process of producing the blue Royal Delft porcelain from the moment it is ordered, cast, decorated, and marketed to the customers.

Craftsmen in the multimedia presentation | photo: Ofer Spiegel The tour continues with theme rooms, such as the authentic dining room of painter Johannes Vermeer, and the complete collection of Delft Blue produced for the Dutch Royal family through the centuries.

So, how is porcelain earthenware produced?Although to all intents and purposes Royal Delft is a commercial manufacturing plant, it plays a significant role in preserving the tradition of porcelain craftsmanship and making it accessible to the public.Since its establishment in 1653, the Royal Delft factory has dominated blue porcelain earthenware production in Holland. It is the only factory that preserves an age-old tradition and which is still operational today. Many factories sprang up like mushrooms after rain when the Europeans were first introduced to porcelain. They sprang up, and disappeared.

Porcelain is a type of ceramic material. It derives its present name from the old Italian word porcellana (cowrie shell) because of its resemblance to the shell’s translucent surface. It is also informally referred to as ‘china’ in some English-speaking countries, since China was the birthplace of porcelain making.Porcelain first arrived in Holland at the end of the 17th century when it was imported by Dutch sea traders, headed by the Dutch East India Company. The craftsmen in Delft started imitating the blue Chinese decorations, adapted it to the local landscapes, and designed decorations of windmills, grazing cows, and traditional Dutch figures, as well as elements from the local painting style. At the end of the 19th century, with the spread of technology throughout Europe, the factories began combining mass production methods with hand painting.Porcelain is made of pure clay in the form of kaolin from which different types are produced that differ from one another in the concentration ratios of additional component materials and firing temperatures. After firing, the color of the clay is opaque white. The higher the firing temperature, the harder, more durable, more translucent, thinner, and finer the clay becomes.

A casting technique is used to produce porcelain earthenware: 1. A suitable mold is prepared, usually made from plaster, but metal molds are also used. The mold has to take into account the object’s extraction angle. A simple mold is made of two pieces, but some are considerably more complex. 2. The liquid clay is poured into the mold, where it remains for a set time. 3. Some of the clay accumulates and hardens on the mold’s interior walls, and the remaining liquid is poured off. The longer the liquid clay remains in the mold, the thicker the object becomes. 4. The object dries in the mold for several hours, and can then be extracted and put aside to dry. The porous plaster mold absorbs the liquid and aids easy extraction of the object.On a shelf at the factory I discovered three vases with which I was personally acquainted – they were part of the Blow Away Vase series designed by Studio Front that combine computerized parametric 3D design and traditional porcelain decorations, and which are actually manufactured at the Royal Delft factory!

5. Once the objects are dry, the seams and irregularities can be smoothed away, before being painted with delicate sponges. If the object is flawed, it is simply tossed into a tub, and the clay is reused (during a tour of the factory I saw first-hand an object that ended up this way).6. At this stage the object is put into the kiln to be fired. After 24 hours the body, which is now called ‘biscuit’, is taken out of the kiln.7. The Delftware painters then paint the object using a water-based paint and cobalt oxide (details below). The painting stage also includes the addition of a decoration on the bottom of the object that constitutes the workshop’s personal seal. 8. In the final stage the object is glazed, and fired a second time at a temperature of 1200°C.

The traditional painting and decorating of the porcelain at the Royal Delft factory is done beneath the glaze, after drying and before firing in the kiln. The artists transfer the decoration onto the object using carbon paper. The painting is done with a brush and black water-based paint containing cobalt oxide, which turns blue as a result of a chemical reaction during firing at temperatures of over 1000°C. The blue stands out against the white background of the porcelain, and this is the origin of the name ‘blue and white’ which objects of this kind are called. No other color is preserved at the high firing temperatures.

Studying hand-painting is no mean feat; it requires a year’s training, and a further ten years to attain the level of master painter. It necessitates a very high level of concentration, since each of the painter’s brushstrokes is final, and cannot be erased in the event of a mistake. After the object has been hand-painted, it is glazed either by dipping into the glaze or by spraying. Over the years, with the production of more modern and commercial objects, Royal Delft, too, has adopted the printed decoration method (which was developed in Britain in the 18th century), whereby the decoration is transferred onto the object after which the object is fired in a kiln to fix it.Royal Delft boasts modern porcelain objects that it has been producing and marketing in recent years, and which are decorated using this technique.

Blue D1653″Call it contemporary nostalgia, new originality or the purest form of Dutch design; Blue D1653 brings together the best design of two eras in one collection”. This is how the new collection designed by Damian O’Sullivan for Royal Delft is described. The name of the collection, Blue D1653, comes from ‘Blue’ for Delftware, ‘1653′ for the year Royal Delft was established, and ‘D’ for design. In short – a contemporary-traditional design collection!

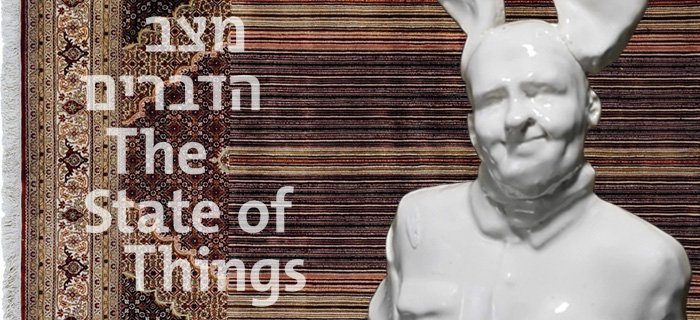

Designer Damian O’Sullivan (who showed his work in The State of Things exhibition at Design Museum Holon in 2010), has created a collection that presents interaction between past and present – distinctively designed objects that pay tribute to the traditional master painters and demonstrate the winds of innovation blowing from the longstanding factory.The collection is being shown in an exhibition at a small gallery near the Royal Delft shop, and is an aesthetic experience in itself. The objects are arranged on platforms around the walls of the gallery and in its center, against a backdrop of shelves on which the traditional blue Royal Delft porcelain objects are displayed, which also provide a deeper historical context.

The objects – plates, vases, bottles, and bowls that are on sale from May – can be used to store food, but also as beautiful, decorative, lifestyle objects.