An interview with Maya Ben David, a designer who is investigating whether people can be clouds and how memories can be turned into objects.

Anyone visiting the recent design exhibition in Milan found it difficult to understand the connection between the collection of exquisitely designed couches and chairs, the harsh economic situation in Europe, and global environmental problems. By contrast, The Machine – Designing a New Industrial Revolution, an exhibition currently showing in Belgium, offers hope and a new way of looking at the future.

Exhibitors in this exhibition, curated by Jan Boelen, the artistic director of Z33, include Formafantasma, Studio Mischer‘Traxler, Unfold, and three Israeli designers: Tal Erez, Itay Ohaly, and Maya Ben David. The latter two are part of a group of Design Academy Eindhoven graduates who were asked to create a continuation to their graduation project.

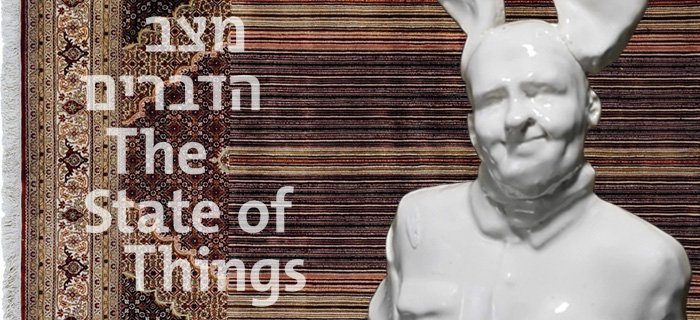

Maya Ben David’s graduation project, which is part of her MA thesis, was recently presented here as part of an article about the Eindhoven graduates’ exhibition in Milan, where she also participated in the Academy’s The Milan Breakfast discussion entitled “The Real Deal”.

In the month since her return to Israel she has traveled to Belgium several times to set up her project, Save As, at the exhibition.

I met her between trips to talk about the project, about memory, and especially about objects that endeavor to counteract forgetting.

Your project, “Save As”, is the practical part of your thesis at Eindhoven; what was the research question?The question was: Can people be clouds? It’s a question that has a lot to do with the objectification of things, and it derived from my need for something physical to remain in a virtual world as well. I tried to take my thinking as far as possible; what would happen if everything became virtual, abstract, and I thought I couldn’t live in a world like that where everything is entirely abstract.

Today the direction of 3D printing of sound waves in increasingly developing; that is, 3D printing of phenomena we can’t see. At the same time, there’s the internet and where it’s taking us, social networks, and services that aren’t on our computer. Most of the things we receive aren’t even on our computer, but on an external server somewhere, and we often discover that we’re searching for something that was there for a moment, and vanished.

I encountered this recently when my sister found out that she’s pregnant and decided to inform us by sending us a photo of the test stick with the blue marking. I was in the middle of something, so I looked at the photo, and carried on. When I wanted to go back to it later, I discovered that I could no longer find it. A lot of things are lost due to lack of awareness. I call it ‘the mental illnesses of awareness’. There are two ends of memory – on one end amnesia, and on the other total recall. The web exists between the two ends. When you remember everything you can’t generalize, you’re incapable of creating hierarchies. And with amnesia, the information is there, but you don’t know how to retrieve it. On the face of it, nothing is lost, but we feel a need to backup meaningful and significant information. The web is ostensibly an infinite space of documentation, but in fact our ability to locate a specific event in our memory archives is almost impossible. Is that, in fact, not identical to forgetting?

Your work engages in memory, which is a totally abstract concept, but you ultimately present objects; how do you get from this research to the object?With computers we generally talk about memory in terms of volume, not in terms of experience. When I talk to someone on Skype for example, I can’t save the conversation. I’m sure this has cultural implications.

There was a researcher in the US who after 9/11 developed a thesis of memory – she called it ‘prosthetic memory’. She discovered that the traumatic events made people who weren’t there remember the events as if they’d actually been there. The web changed the intensity of what we experience emotionally. We participate in events that occur in different places around the world even if we weren’t actually there.

That’s how I experienced the tsunami in Japan and the revolution in Egypt. I tried to understand what were the central links that shaped what I experienced. With the tsunami in Japan I saw again and again the image of the cars being swept away by the water. We’re all documented, but when you filter the images you discover how many similar images there are. It seems that everyone’s thinking about what it’ll look like on the web. People upload images that have no innocence in them, that lack a clean message.

It seems that everybody’s thinking about how it will be presented. A lot of heroic images remained from the revolution in Egypt. Very few wounded and dead, and a lot of symbolic images – like a pyramid looming over people standing or kneeling on a tank, pictures of birds that symbolize freedom, or images of people climbing onto symbols of the regime. A lot of things that are connected with the strength of the public, like carpets of worshipers, images that in the main are highly aesthetic. All disasters have images that look like mass-produced pictures; they possess repetition that creates an aesthetic. But the internet experience is not only images; it is one that is formed from all kinds of media. There’s also a silence that attends events like this. In the plates I tried to take the image of the cars as well as the silence that horrified me, and convey in the plate the feeling of the water sweeping away the cars.

With the revolution in Egypt I referenced the historical vase that tells stories. Throughout history vases have served as a platform for conveying information. I chose the central images that accompanied me throughout the revolution and created a collage. The choice of images was very subjective. I experienced the revolution in Egypt as excitement and I wanted the vase to convey that excitement.

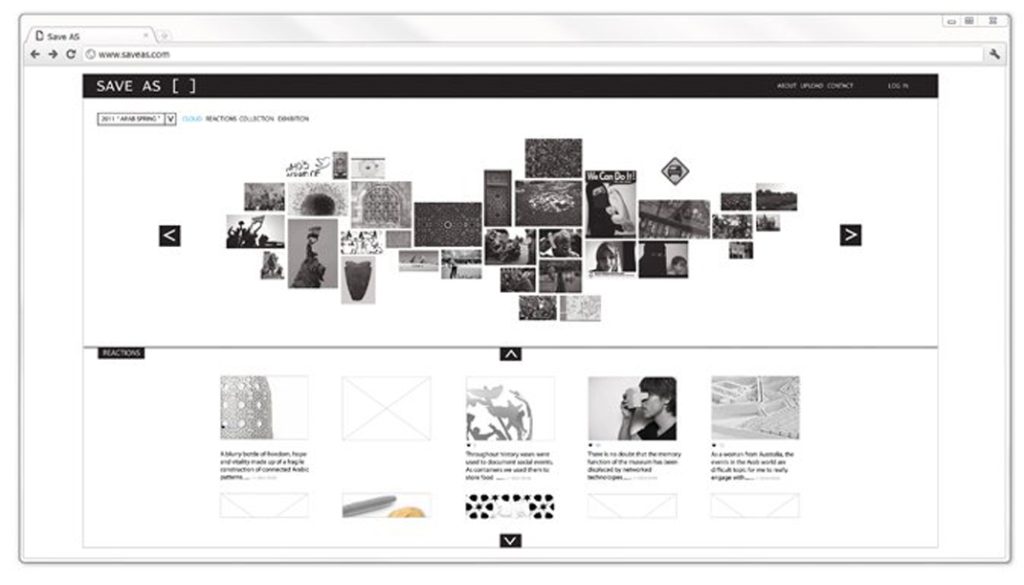

Your project “Save As” is not only a tool for personal expression or a reflection of your memory, but a platform shared by other designers.When Jan Boelen invited me to participate in the exhibition, I was asked to adapt the concept to the historical context of the venue (a coalmine in Genk, Belgium), and continue developing the project. I decided to collaborate with designer Jon Stam and creative artist Roee Kremer and create an installation based on 3D printed objects together with an application that was presented by means of iPads. We approached designers and asked them to create objects from their internet experiences. I didn’t want it to be a collection; I just wanted them to convey what they experienced. There were two designers from Germany who chose the Islamic arabesque as a form of communication and an image of infinity, and created an object that shows where communication can go in terms of sharing. Another designer, who created the Coke bottle, tried to show what happens in the encounter between images that Egypt adopts from another culture into its own. Through this platform I felt that something moved and changed. Designers usually find it hard to express themselves in political contexts, to reveal their opinions. They prefer to serve as a tool. The political subject sits like something that’s hard to take apart as a design creation. At least in my generation. With this platform things started to come out.

Your project is currently showing in a completely different venue to Milan; what does it look like there?The entire exhibition is presented in a shut-down coalmine, and its objective is to indicate that although industries vanish, they have new continuity. The venue is a kind of monument. Jan asked us to adapt our concept to the venue. We walked around it and realized that it was a phenomenon that occurs in all kinds of places around the world – of an industry vanishing and something being created in its stead. We saw the Genk mine as a starting point and symbol for processes that are taking place in various places around the world. We were interested in making a connection between the different places and showing the similarities.

In the mine where the exhibition was mounted there is a very iconic red and white tile floor. We chose to refer to the historical grid of the place and blend in with it. We wanted to create a layer of intimate memory in the physical place. We designed a 3D tile with the same dimensions as that of the historical tiles and distributed it to designers with a brief. They were asked to respond to the phenomenon of vanished heavy industries like the coalmine in their own localities. For example, an Israeli designer who lives in Venice described the glass industry in Murano that died out and was turned into tourist excursions. He took the glass blowing machine and turned it into a soap bubble blowing machine.

In Milan it seemed that at least the schools presented a lot of designers who make their own machines. Is this a new trend?Yes, accessibility to technology is increasingly diminishing. There are hardly any platforms nowadays. There are crafts that are vanishing, and designers have no choice but to manufacture for themselves, and there’s a correlation with internet systems that shows the extent to which people want to be capable of manufacturing. There’s something about open code that enables people to create and live within a system that creates something. There’s something wonderful about open code. But what gets in the way is ego.