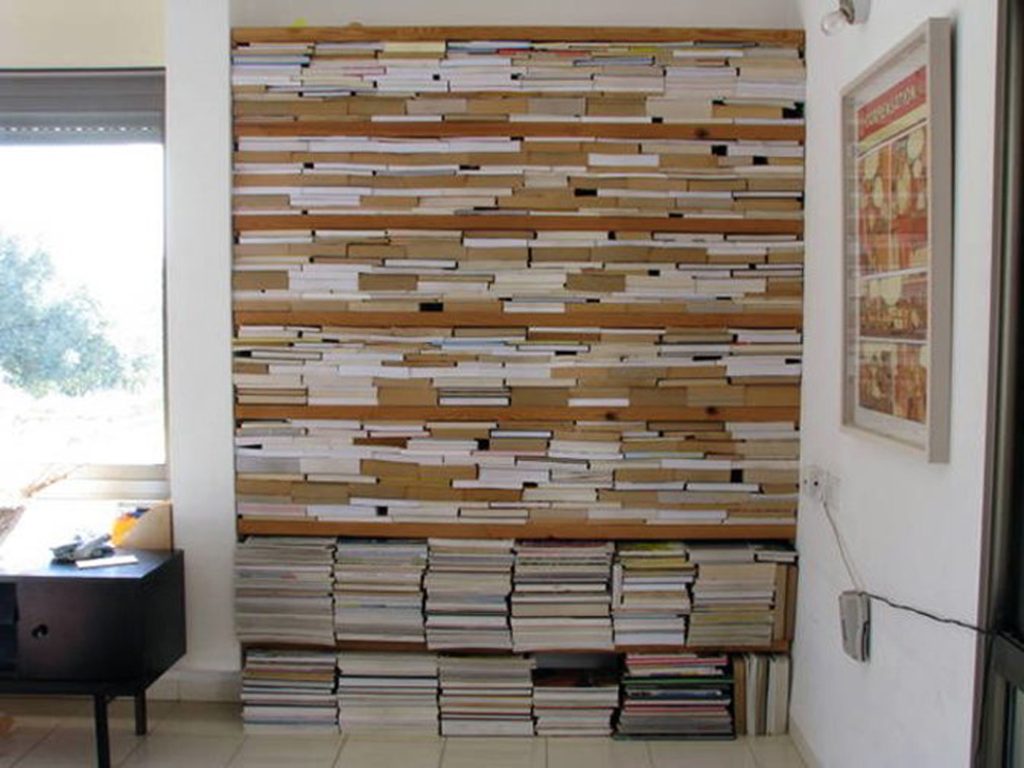

She recently won the prestigious Andy Prize, and her first solo exhibition was shown last month at Periscope Gallery in Tel Aviv. An interview with textile designer Gali Cnaani. Gali Cnaani’s solo exhibition OSLO XXL opened on one of stormiest evenings Tel Aviv has seen this winter. Despite the cold weather outside, inside the gallery space (Periscope Gallery) it was warm and intimate. On one side of the gallery small woven pieces are displayed, while on the other side framed photographs of books hang on the wall. In the center of the exhibition space is a large heavy bookcase showcasing the books themselves.

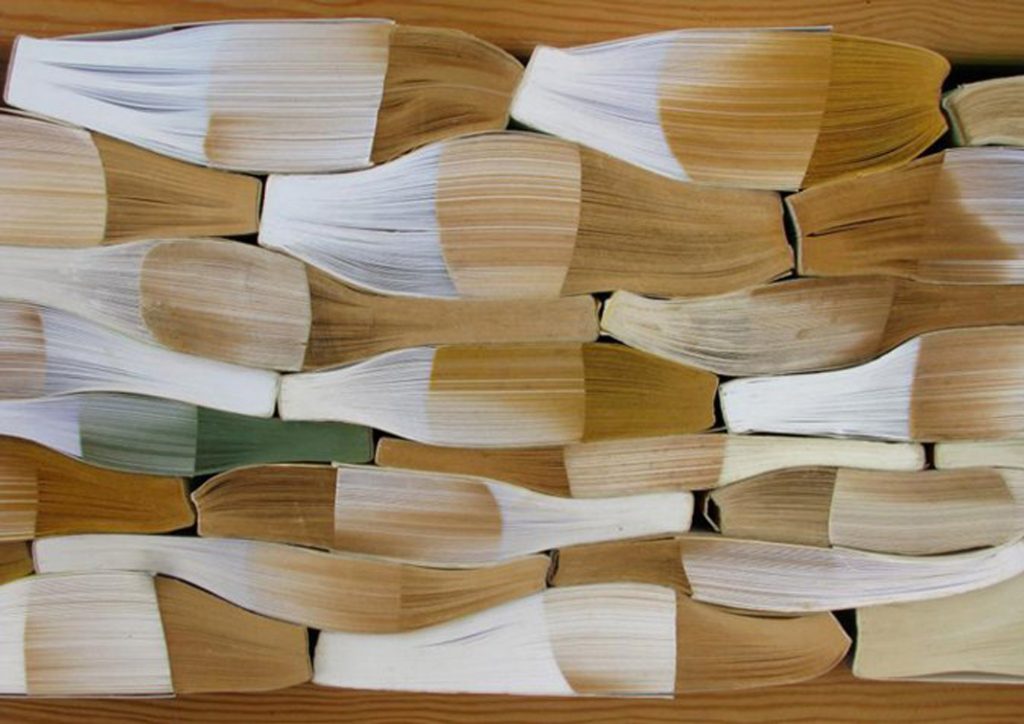

The first question that comes to mind is: What’s the connection between books and textiles in general and weaving in particular? The world of literature and the craft of weaving have several convergent points: like reading a book, weaving on a loom is an intimate act done quietly and alone.; the two actions, weaving and reading, are performed on a time continuum, with breaks interrupting the continuity; there’s also a lot of visual resemblance between the two worlds – from the side, the dense warp threads in the loom look like the pages of a thick book.

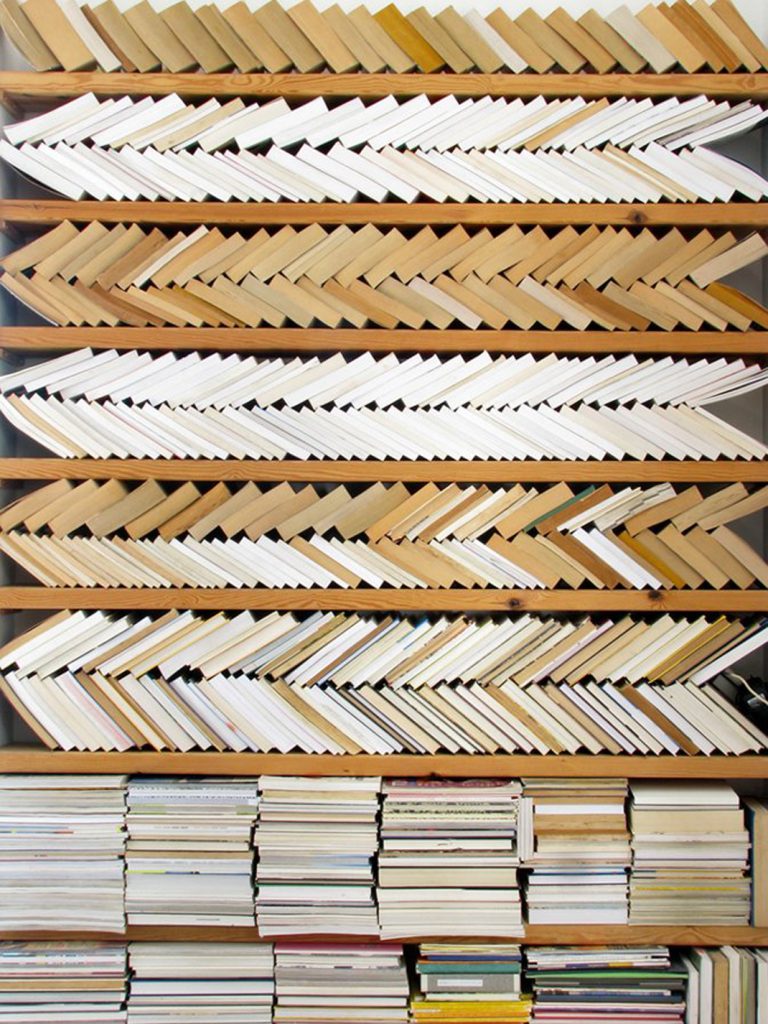

Cnaani has turned this resemblance into a tangible connection in a series of works presented in the exhibition entitled Pattern Book. It is a series of fascinating photographs that are the result of working on her bookcase at home. It seems that the pieces in the exhibition are just a glimpse of what can be developed from them in the future. One can already imagine an entire fabric dictionary woven from the pages of these books. What will drill, pepita, or even piqué look like?

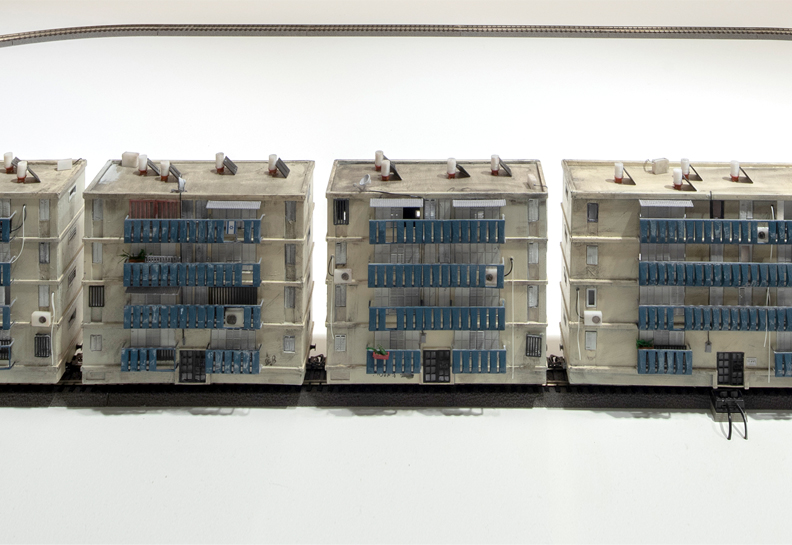

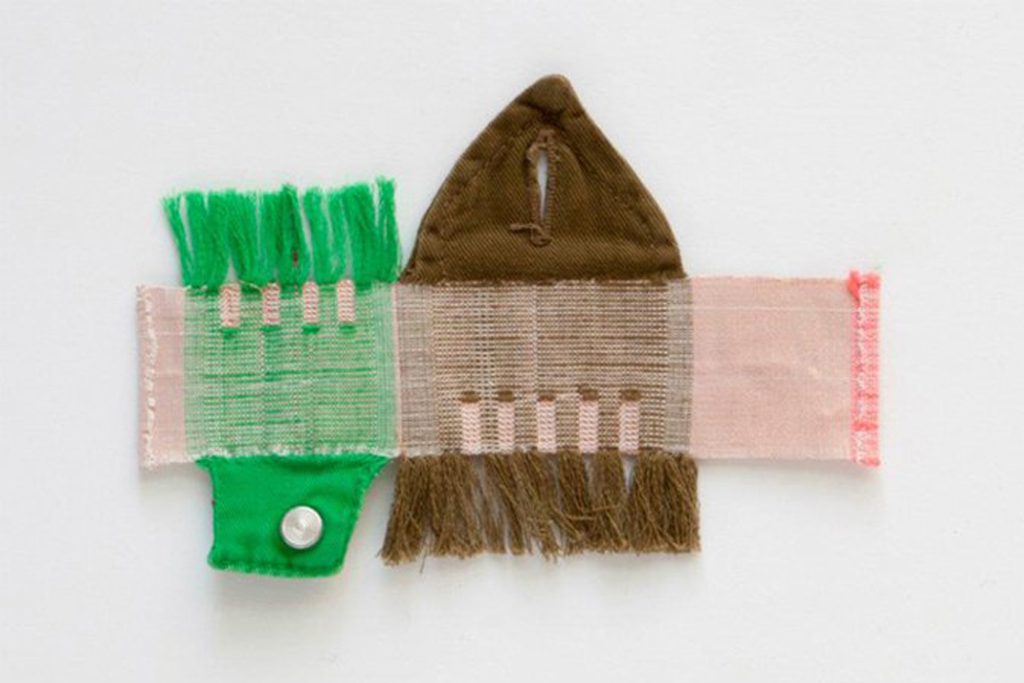

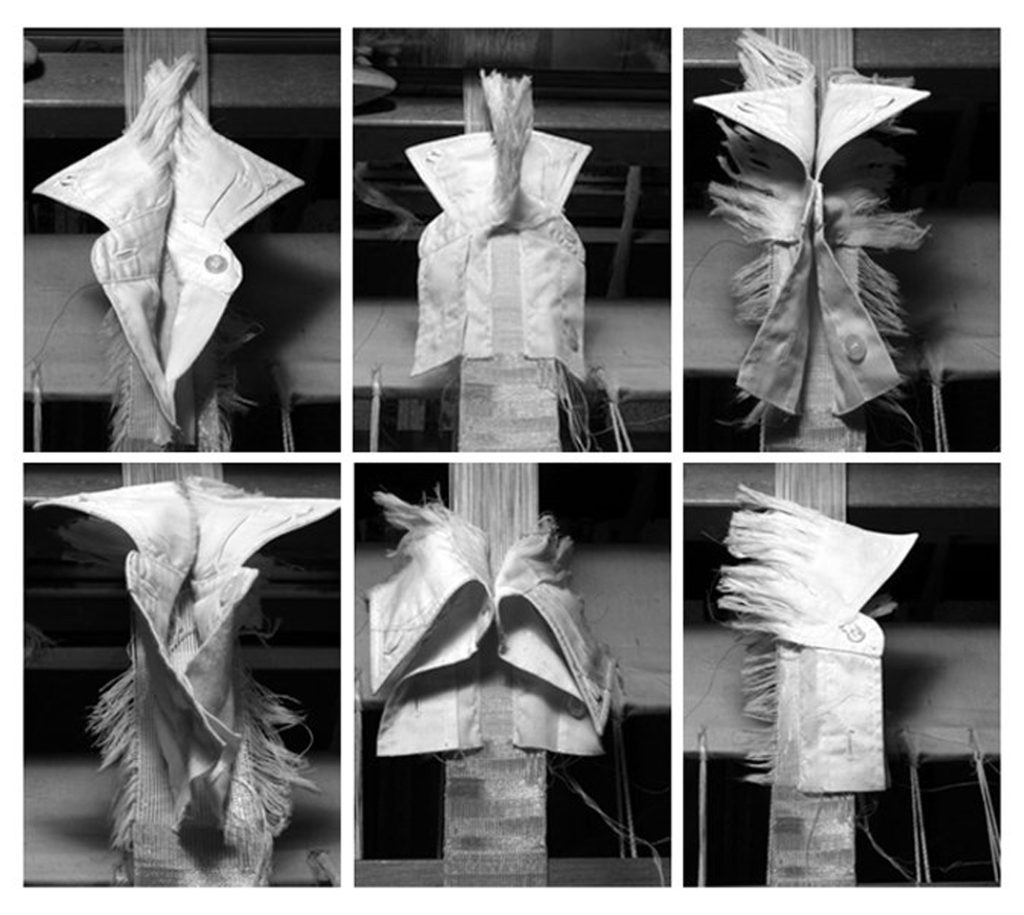

The second part of the exhibition consists of small woven pieces displayed under glass: parts of different garments, a cuff, a sleeve, buttoned-up buttons. Cnaani’s woven pieces were painstakingly created on a handloom with great attention and infinite patience of the kind that can sometimes only be truly appreciated by a select few. Cnaani chose garments, unraveled parts of them, and then rewove them into the loom’s warp threads. This entailed meticulous, intricate work due to the fact that she used very densely set (30 threads/cm) white sewing cotton for the warp threads.

It’s also interesting to ponder the relationship between literature and weaving through the created metaphor. The pages of a book are filled with words, paragraphs, a story, pictures, just as the threads of a fabric create an image. The woven pieces of printed material are a good example. The original print was unraveled and recreated with Cnaani’s intervantion.

The two different parts of the exhibition complement as well as strengthen one another. Moreover, it seems that in the ‘book’ pieces there is a kind of playfulness and relief from the concentrated loom work. One can imagine Cnaani working for hours, taking out the books, sorting them according to size and color, and rearranging them in an improvised ‘loom’ with the desired image in her head, which is actually a weaving pattern.I met with her for a short interview:Where does the name of the exhibition come from?All the names of the pieces are very laconic. I didn’t want anything too charged with meanings. OSLO evokes various associations, but in all of them there is a sense of distance. The XXL refers to the world of garments, of fashion. I also liked the idea of using XXL as a title for very small pieces.

In fact the name OSLO XXL is taken from the label of one of the shirts in the exhibition. Yes. Everything is coincidental and with hindsight of course. All the clothes used in the exhibition are second-hand garments that I collected, received, and bought. It was only afterwards that the label on one of the shirts, OSLO XXL, suited me as a name for the exhibition itself. One of the interesting viewpoints of the exhibition is that of student-teacher-student. Cnaani began her career in the Department of Textile Design at Shenkar College of Engineering and Design, where she studied for four years with Yeshayahu (Ish) Gabbai, the exhibition curator. Today she lectures in the Department of Textile Design at Shenkar, and in the Departments of Jewelry and Fashion Design at Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design. Tell me a little about your special relationship with Ish and the joint work process in the course of preparing for the exhibition. Ish and I have kept in touch ever since my graduation. Over the years I have accumulated a large body of work, and I felt it was time for a solo exhibition. I immediately asked Ish to curate it, and he agreed without hesitation. His guidance was very subtle. He doesn’t say much, and that is really typical of our relationship ever since my student days. One word from him is enough to give me an idea on how to continue forward. He analyzes things and lets me see them from his perspective. I didn’t feel like a student, but on the other hand Ish will always be my teacher. I am constantly learning from him.

You are three sisters, all of you in the arts and with a strong connection to the world of textiles. Shiri is a textile designer and Roni is a photographer, focusing mainly on fashion. How did that happen? During several seasons my mother made knitwear for Rojy Ben-Yosef. She has no formal education, but she’s got what it takes. Riki Ben-Ari (a leading fashion illustrator at the time) introduced them, and she designed knitwear that was sold all over the world. She continued knitting on a home knitting machine and then opened a shop for handmade items, where embroidery classes were also held.

My mother’s father died very young, when I was 12, and he was the meister, the master craftsman at a weaving factory in Migdal Haemek called Emek Textiles. I didn’t know that until I was much older. Not long ago we found all kinds of small weaving samples of his, as well as his diploma from his studies in Bucharest. There’s something very meaningful about this connection with my sisters, there’s a constant dialogue. Roni always photographs my work, and she also took the photographs for the book accompanying the exhibition. Shiri (who is participating in the Designers Plus Ten exhibition at the Museum) and I maintain continuous dialogue, consultations, and mutual critique.

Both Shiri and Roni live and work in Tel Aviv. Do you think that the fact that you live in Tivon influences your work?I feel very connected to the city; I lived in Tel Aviv for at least ten years. I have always worked in Tel Aviv one or two days a week. On the other hand, there’s this complexity. Returning to the landscape where we grew up. It makes it harder for me because I don’t get to see all the exhibitions in the center of the country. On the other hand, the natural landscape here is very significant and I’m sure it influences me; it provides a great deal of inspiration. Today I am much more connected to the seasons. I love the winter. When I’m here in the forest and there’s a very dry winter, it’s really depressing. Maybe what I see as a disadvantage sometimes becomes an advantage, because I’m less influenced by what’s going on in the center of the country from the creative aspect as well.

Cnaani’s exhibition is accompanied by a beautifully-crafted book containing articles by Yeshayahu (Ish) Gabbai, Katya Oicherman, and Anat Zecharya. The book was designed by Gal Sinay as part of a book design course given by Avigail Reiner at Shenkar’s Department of Visual Communication. At a very early stage we decided to create a book that would be a separate project in which the pieces could exist in a different form. While working in the class and searching for the right way to combine my weavings in a book, I started working on the series of book photos showing in the exhibition. The bookcase on display at the gallery is an almost identical replica of the one in my home. For three months no one could read a book at home. I usually worked at night. I always began by sorting the books according to size, height, width, and color. The brown books belong to my husband, Nadav. He reads fantasy books in English. With these works I experienced quick gratification; within a few hours there’s already a result, in contrast to working on the loom, which can sometimes take two weeks. There’s also something dynamic about it, a kind of break from weaving.

For Cnaani this is the beginning of a very exciting year: her first solo exhibition, in addition to winning the prestigious 2012 Andy Prize. Tzuri Gueta, also a textile designer and Cnaani’s Shenkar classmate, won this prize two years ago. To my question about how she sees the development of textile in Israel, she responds: The field is currently transforming and seeking new directions. We’re in a time of significant metamorphosis. In my day we were very industry-oriented. There were factories and each factory had an in-house designers’ studio. There are only a few designers from my class who work independently. Today’s graduates will be the ones to bring about the change, and I see it as a very interesting time.