A tour of the graduate exhibitions with an eye to the unrepresented projects

The press preview of the graduate exhibitions raises questions about the influence of politics on the decisions made concerning the exhibitions, and about what makes a project photogenic and one that quickly becomes a conversation piece. This article is not based on extensive experience or years of viewing graduate exhibitions, but a perspective that emerged from within design studies and transitioned to the outside world.

As in any field – and the field of design is not exempt from this context – politics plays a central and decisive role in the choices and considerations associated with exhibitions. In many design schools the department heads seek a project that represents their department the way he or she wants it to be perceived. Some departments go even further, showing the press only the projects they would like to be represented. Thus, they in effect decide for us what is less or more important or interesting. Moreover, they decide what design is for the broader public.

I do not seek to engage in the obvious visual context of the word “photogenic”, but rather in photogenic as embodying the qualities of the projects that are chosen to represent the academic institution in which they were created. The photogenic project will be the one placed in the most prominent and desirable position in the graduate exhibition, and it will be extensively written about and reviewed in the press.

The admixture that creates a photogenic project requires first and foremost an invention or discovery, it should include collaboration with a well-known commercial company, and be a functional product that embodies the invention while ensuring that it is not overshadowed by its design. Something sufficiently general, and at times even noncommittal. The extensive research projects are those that ostensibly present greater depth, but they are usually overlooked in the name of discovery or originality. Some might even call them a “gimmick”. Projects of the type that discuss a burning contemporary issue and are perceived as social or community projects, or which are designed for special populations, are likely to be exceedingly photogenic projects. The “apparently non-photogenic projects” are those that engage in something familiar. But it seems that choosing to delve into scissors or a pencil facilitates attention to the finer details, and requires substantial depth and a higher resolution.

While wandering around the graduate projects, I found myself asking why the focused-investigative projects are never the ones to occupy center stage. I am referring to projects that embarked from an observation of the basic home environment, selected a single, familiar object within it, and based an entire in-depth study on it. They delve deep into our habits, into the cultural constructs that have been built over decades and even centuries. The construct that causes us to hold an object in the way we are accustomed, to use it in a particular way, and call it by its name. They look back from a historical perspective and examine the development of a familiar everyday object and how it has evolved over time. I would argue that projects of this kind are not merely “charming”, but actually embody the pure work of a designer. So, while it is true that new discoveries and “inventiveness” are always desirable, is it not more intriguing to actually look at a familiar object and through it discover new things? Besides the issue of politics in this field, part of the problem is possibly the lack of clear boundaries demarcating the design field and the absence of a definition of the designer’s work.

Different approaches provide a wealth of definitions for the designer’s role in society. Some emphasize a connection with the economy and consumer culture, while others underscore the proximity of design and art. Like many other researchers, Dr. Jonathan Ventura argues that like an anthropologist, an industrial designer engages in people and focuses on their everyday life and social and cultural functions. Based on this approach, I found several projects engaging in people that are worthy of occupying center stage:

Carla Rataus’s project engages in an exploration of the archetype of scissors. In the course of her research she analyzed the structure and various component parts of scissors. She deconstructed and reconstructed the object in order to study its DNA. Her products include some that establish improvised cutting habits that were formed specifically when there were no scissors around.

For a whole year Yaakov Goldberg conducted a research and design study focusing on the lollipop as an industrial product and an iconic object with formal, historical, functional, and cultural contexts. He delved into the roots of the candy, its combination with a stick, and its cellophane wrapping. Besides the candies as products, Yaakov presented his research in a detailed book in which he finds innumerable creative contexts for this very familiar product.

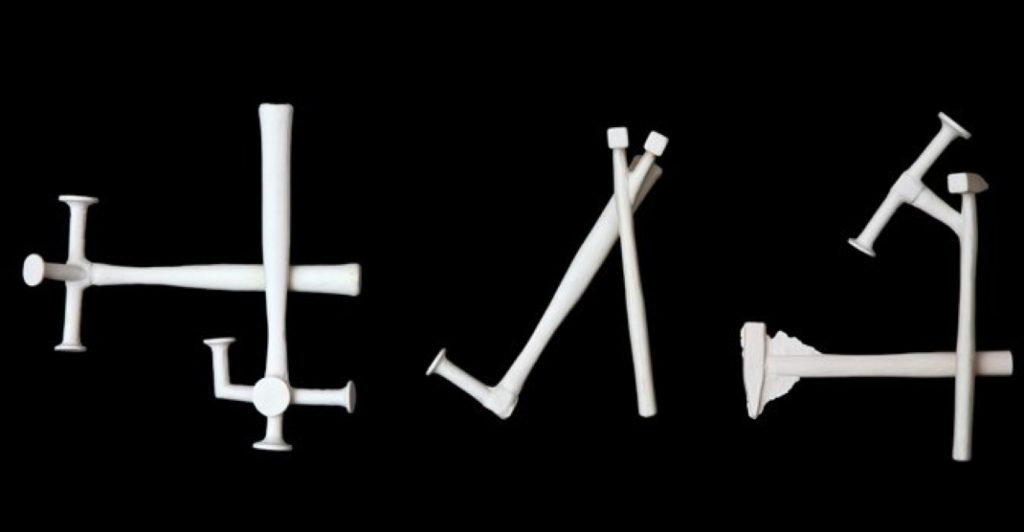

It was actually in the Department of Ceramics and Glass Design that we found an interesting study on a hammer. The project engages in exploring the seam line between a hammer as tool possessing an aggressive physical presence, and the fragility of clay. The fusion of hammerheads presences the seemingly impossible connection between the two worlds.

It may be assumed that observing the four projects presented here would not raise a question such as “What is that?” However, work processes of this kind may have greater influence on society over time, and it is they that constitute the basis of the designer’s work. Not necessarily the innovative invention.

This is the first in a series of articles on graduate exhibitions showing at the various design schools, which are currently open to the general public.