In an interview with designer Stefan Sagmeister, Michal Or-Ad tries to find the boundaries of happiness.

In an interview with designer Stefan Sagmeister, Michal Or-Ad tries to find the boundaries of happiness. His exhibition in Philadelphia explores whether it is possible to train the mind the way we train the body.

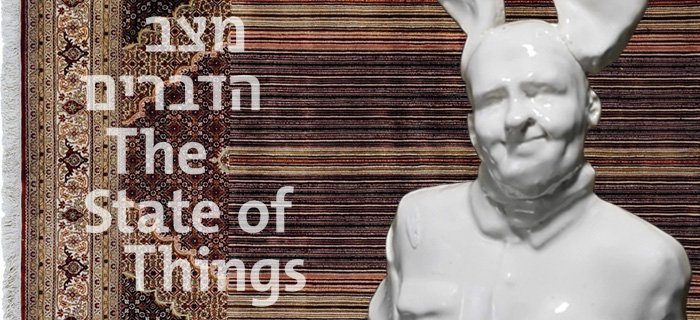

In his latest exhibition, The Happy Show (at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia up to the end of August 2012, and at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles later this year), Stefan Sagmeister presents the results of his ten-year exploration of happiness, manifested in typographic investigations of a series of maxims, or rules to live by, originally culled from the designer’s diary.

Born in Austria in 1962, and living and working in New York, Stefan Sagmeister is one of the most prominent and interesting graphic designers in recent years, and he has garnered virtually every possible design award. He initially became known due to his commercial designs for the music industry: The Rolling Stones, David Byrne, Lou Reed, Aerosmith, and others. In his work he tests the boundary between art and design, mainly through highly imaginative experimental typographical research. His work is innovative, ambitious, at times even unsettling, and manages to stand the test of time and remain fascinating and relevant.

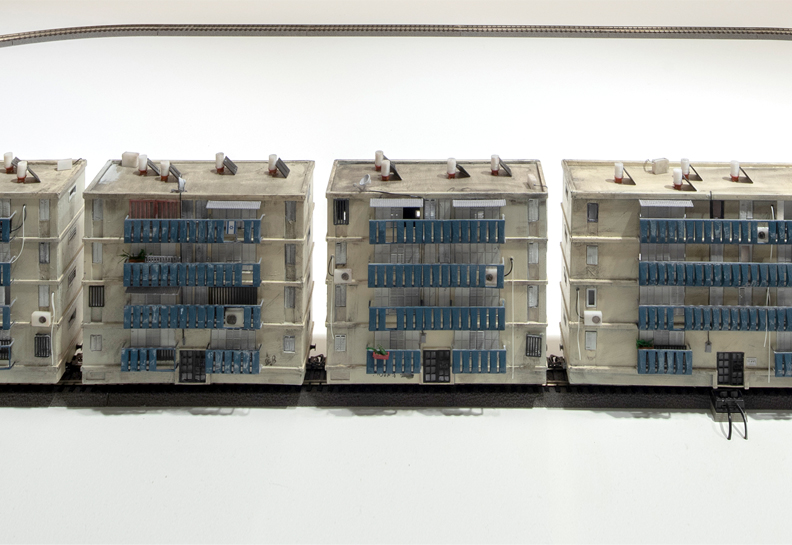

“The Happy Show” is Sagmeister’s first museum exhibition in the US. At the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia it filled the entire second-floor galleries and Ramp, and the spaces between floors. Visitors get the sensation of walking into the designer’s mind as he attempts to increase his happiness via meditation, cognitive therapy, and mood-altering pharmaceuticals. The maxims, or rules to live by, that feature in the exhibition were originally culled from Sagmeister’s diary, and later backed up by the sociological research of various prominent psychologists, anthropologists, and historians.

The exhibition also includes The Happy Film, a 12-minute film that explores whether it is possible to train the mind the way we train the body. Sagmeister employs various means, such as infographics, print, sculpture, and interactive installations that incorporate personal stories and social data in order to investigate the degree to which factors such as age, gender, race, and money influence our happiness.

What triggered the exploration of such a wide-ranging abstract concept like happiness?I lectured about design and happiness for a long time, and I always received positive feedback. The feedback was the main catalyst for investing time in exploring the concept.

What were the sources of inspiration for the exhibition?The exhibition was created as a development of the film. In the course of working on the film, a lot of ideas came up that would work better as physical exhibits, which are easier to relate to than a film. When we were invited to create an exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia, that was the most logical direction.

What other subjects do you plan to explore in the future? Will some of them include similar ideas and engage in emotions?Yes, I think so, I feel that design in general is too rational and too professional; the emotional parts rarely gain expression. I see that emotional directions, as well as more didactic ones, haven’t yet been explored.

Do you implement some of the techniques you’ve learned in your creative and thinking processes?Yes, it definitely becomes part of my life, and certainly part of my design process. Many of the “Things I Have Learned In My Life So Far” relate directly to the creative process, like for example “I Actually Do The Things That Increase My Overall Level Of Satisfaction” or “If I Want To Explore A New Direction Professionally, It Is Helpful To Try It Out For Myself First”.

Do you set yourself a deadline for projects like the documentary film, which is clearly very personal, or do you believe that projects like that can’t be rushed, and work on them until you feel they’re ready?Yes, we do have a deadline. I think that if projects like that go on for too long, it’s hard to stay excited about them.

Do you consider graphic design a job, a holiday, or a bit of both?It varies. When I opened the studio I considered the work a vocation. The sense of vocation diminished over time, when the work became routine; designing the twenty-second CD cover was less enthralling than the first. During my sabbatical – a year off from clients, which I take every seven years – it became a vocation again.

What else can you tell us about the film and about happiness?I’d be happy to find an answer to the question of whether it really is possible to train the mind the way we train the body. Can I – by using different techniques that might include acts of generosity, writing a diary, and meditation – increase my overall level of happiness? While several serious psychologists are convinced that this is the case, I’d be happy to prove it to myself and to viewers.