In an article Van Herpen relates that when some people see her designs they feel fear, and wonders why it is this emotion that they express.

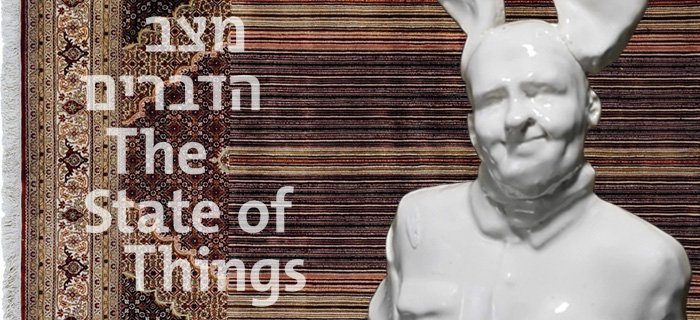

Why are we afraid of Iris van Herpen’s dresses?

In an article published in the catalogue of the Iris van Herpen exhibition in the Groninger Museum in Holland, Van Herpen relates that when some people see her designs they feel fear, and she wonders why it is this emotion that they express, “after all, the dress is never going to attack them”, she says.

She is, of course, right; her dresses will not attack spectators, they will not sprout legs, grow a brain, or bare fangs. But two significant factors stand behind the tingling sensation that runs down your spine when you look at the designs she creates. Designs which move along the polarity between natural biological inspiration and futuristic, mechanical craft. One is the process behind the garment, a technological process that seems futuristic and mysterious to many people, and the other is the appearance of the designs that moves between a simile of the bones of otherworldly creatures and close-ups of insects, which cause discomfort in a large segment of the population. However, based on her tremendous success, we are clearly still attracted to Van Herpen’s designs, and the question is what makes us examine her work despite this emotion, and how do we end up enjoying this emotion?

Designed technophobiaIn her work Van Herpen relates to technology and the digital world from different angles, some based on using technology to create her designs, whether 3D printers or 3D software, and some are manifested in the sources of inspiration underlying each new collection.

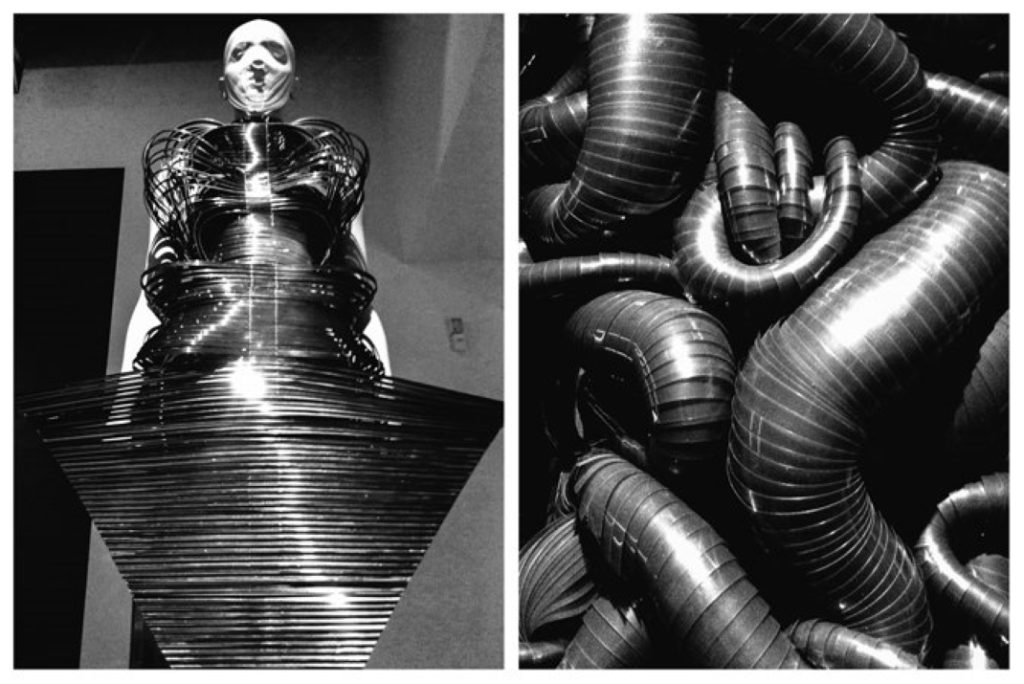

In her “Radiation Invasion” collection (September 2009) Van Herpen contended with the digital information surrounding us in the technological era and which is saturated with microparticles and nanosized objects. She addresses a digital world that does not stop for a moment, an invisible world consisting of flickering patterns and vibrating particles, a universe in perpetual motion in accordance with laws that are incomprehensible to ordinary people. For this collection she created a dress made from glittering elongated sequins that move with the body, constantly rustling like those particles of information. The collection also featured swirling strips of leather, an inanimate material that appears to be in constant movement. The leather received various treatments, and Van Herpen combined it with materials from other worlds, such as porcelain, shiny metallic materials, and snake skeletons, leaving spectators to wonder whether these are indeed biological materials, or artificial substitutes.

In contrast with “Radiation Invasion” which was inspired by technology, “Crystallization” (July 2010) utilized technology to build the designs themselves. This was the collection that brought Van Herpen world fame for the first garment made entirely using 3D print technology, a collaboration with architect Daniel Widrig and MGX by Materialise. From an anonymous young designer Van Herpen instantly became one of the designers spearheading futuristic fashion. Following this collection she has repeatedly been asked, “Where is the fashion world going?” and “Will the 3D printer bring about the second industrial revolution?”

Her “Escapism” collection (January 2011) is based on the notion of people escaping from everyday reality to the digital world. Dwindling communication, the constant need for entertainment, repetitiveness, and distorted reality in the alternative digital world led Van Herpen to create designs that distort the body by means of repetitive, identical elements. In this collection she incorporated 3D printing in a kind of lace, according an alternative, technological, modern interpretation to the ancient tradition and vanishing handcrafts.

In her most recent collection, “Biopiracy” (March 2014), alongside the models walking on the runway Van Herpen showed an installation comprising models inside plastic vacuum packs as the air was slowly sucked out of them. With about one third of the human genome already patented, in her installation Van Herpen raised the troubling question regarding human replication and cloning, and provided spectators with a glimpse into a world where humans will be a purchasable commodity.

There is no doubt that Van Herpen’s distinctive garments stimulate the entire gamut of human emotions, and as with other works of art, spectators can feel discomfort, confusion, or bewilderment, and they can also feel wonder and amazement. These are all emotions that people are accustomed to when viewing works of design and art. But the fear to which Van Herpen refers when viewing her garments is an emotion that is generally perceived as negative, and is only rarely associated with garments, which usually enjoy good public relations of softness, joy, pleasure, and dressing up. That being the case, what makes Van Herpen’s designs the exception to the rule? And what is the source of this emotion when looking at her garments?

It seems that it lies in the principal difference between Van Herpen’s creations and regular clothes and fashion, namely the materials and technologies she uses. In her work Van Herpen, who burst into our awareness primarily due to the 3D printed dress she created, employs innovative technological developments. She seeks assistance from relevant professionals to realize her vision using complex, original, and even experimental tools. The fact that she works with the most advanced computer programs to create her garments makes the needle and thread seem light years away, and with them the traditional, human methods of sewing and making clothes.

With the development of technology that is taking over virtually every aspect of our life, a substantial number of people openly express fear of technology. But technology was not always intimidating. During the eighteenth century robots were built that could mimic human actions such as walking, singing, playing a musical instrument, and dancing. They were presented to the public and were not perceived as a technological threat to humans. However, with the start of the Industrial Revolution in the nineteenth century and the introduction of huge machines that replaced human workers in the factories, attitudes toward technology began to change. A new term has been coined in recent years to describe this fear.

Technophobia is the fear or dislike of advanced technology or complex devices, which contrary to initial assessments is becoming increasingly more acute as technology continues to develop. In its lower levels, technophobia is manifested in an irrational negative attitude and reaction to advanced technology. Examples of technophobia can also be seen in works of art, such as Mary Shelley’s novel Frankenstein, and the films Metropolis by Fritz Lang, and Modern Times by Charlie Chaplin. These examples engage with essential aspects underlying technophobia, as does Van Herpen on the conceptual level, presenting them visually through her groundbreaking collections: How to separate organic life and industrial alienation, how to think about genetic engineering and the creation of artificial life, how to avoid mechanical, robotic enslavement over which humans are losing control, and how to think about the flow of information that envelops us yet remains invisible to us and beyond our comprehension.

Cognition, art-horror, and science fictionFor her sources of inspiration, Van Herpen consistently returns to the living and microscopic worlds, and examines and investigates the human need for control. Van Herpen’s control does not only apply to knowledge and the living world, but is also manifested in her desire to tame and harness natural phenomena and liquid or gaseous substances for the purpose of making garments. She examines the human attempt to gain maximal understanding of the organisms around us, and projects her conclusions onto the way we behave, constantly circling the need to break boundaries. This breaking of boundaries by Van Herpen could be one of the explanations for the sense of fear spectators experience when viewing her garments.

According to art philosopher Noël Carroll’s article The Nature of Horror, breaking accepted cultural boundaries is an action that makes the spectator feel discomfort and fear. In recent years the art-horror genre has developed and become a central source of aesthetic stimulation for the masses. Horror novels have become increasingly widespread, and authors like Stephen King have become household names. Featuring among the films with the highest viewer ratings are horror films and TV series such as American Horror Story, have become popular not only with confirmed aficionados of the genre. Alongside the increase in vampires, zombies, and other imaginary monsters, the inclination for art-horror can also be seen in arts, e.g., Francis Bacon’s paintings or the detailed biomechanical illustrations of H. R. Giger.

In works of art-horror the humans regard the monsters they encounter as abnormal, as deviances of nature. When they encounter supernatural creatures in cinema or literature, viewers or readers will reflect the reactions of the protagonist; if the protagonist displays revulsion or fear toward the monster, so will the viewer. However, if the protagonist accepts it as part of the nature of the imaginary world (e.g., Chewbacca in the Star Wars series, or fairies in fairy tale films), the viewer too will not experience feelings of horror or fear, and will even develop feelings of affection toward it. In contrast with the imaginary creatures that gain the viewer’s sympathy, the negative monsters encountered in the cinematic, artistic, or literary narrative will be identified as impure and unclean, they will often be composed of dead or rotting flesh, chemical waste that is identified with disease, or crawling things that evoke feelings of horror and revulsion in the viewers.

In her collection, “Micro” (January 2012), Van Herpen transforms a hidden reality into a visual reality following the photographs of Steve Gschmeissner that present images of creatures magnified through a microscope. Cellular structures, plasma, tentacles, organisms, protrusions, forms and shapes, armature, and scales all gain expression in Van Herpen’s work by means of polyamide, Perspex, leather, metal sheets, cashmere, and other materials. In this collection Van Herpen included shoes that she designed and then 3D printed, which were called “Fangs” due to their shape, ranging from the image of a predatory animal to the cultural image of vampire fangs.

According to Carroll, the emotional state caused by art-horror is primarily cognitive, and sometimes engenders physical effects. Expressing emotions does not only entail deviation from the routine, but also cognitive thoughts and analyses that lean on the characteristics of objects and situations. In Purity and Danger anthropologist and culture researcher Mary Douglas draws a connection between negative reactions toward things whose attribution to cultural categories is difficult. For example, four-legged insects evoke revulsion since four legs are characteristic of earthbound creatures, whereas these insects fly; consequently, they are a kind of category mistake, and hence impure, and evoke negative feelings. Moreover, according to Douglas, objects can arouse misgivings when they do not fully present the category to which they belong, or if they are formless, like soil and dirt.

In her collection “Refinery Smoke” (July 2008) this is precisely what Van Herpen touches upon: elusive, incomplete elements that are difficult to define, to categorize. Her inspiration for this collection is smoke – elusive, ambiguous, and moving. In culture it is often perceived as sinister, menacing, and toxic. Using a metal fabric woven especially for her from very fine metal threads, Van Herpen created a dress that simulates the ambiguous substance. Although they do not disperse, Van Herpen’s threads underwent a material change process hidden from the eye, and over time oxidized to a reddish-brown color. The attempt to catalogue Van Herpen’s objects in this collection under accepted categories poses a challenge, and emphasizes our need to express an emotion that deviates from the familiar.

If we accept Douglas’s theory, we can assume that an object or entity is considered impure if it belongs to multiple, contradictory, incomplete, or formless categories. Category incompleteness typifies many horror creatures, including ghosts, zombies, or skeletons in one stage or another of decay and decomposition. Many imaginary creatures in visual media as well as the written novel or literature are based on the formless biology of terrible impurity, and by providing vague descriptions of their basic biology, leave viewers with an impression that has no foothold in the familiar, calming reality of whole, safe forms. Even when they do possess the characteristics of an established category, some of these creatures are magnifications of animals, insects, and reptiles already judged impure and horrible in the folk tales and arts of the culture.

In “Capriole” (July 2011), the collection with which she made her debut at Paris Haute Couture Week, Van Herpen showed a dress that was nicknamed the “snake dress”. Made of black acrylic sheets that twist and intertwine, the dress gave visual expression to the designer’s mental state a moment before making a freefall parachute jump. The other designs making up the collection, especially the 3D printed garment that looked like the bare bones of a creature conceived in human imagination, send the spectators’ thoughts drifting toward the realm of horror and impurity represented by snakes.

The emphasis Douglas places in her study of impurity on the division into categories attests to the way we are able to point at “impure” creatures and describe them as “unnatural”. They somewhat resemble the cultural perception of nature, but do not fit in; they violate it. Consequently, these creatures are not only physically threatening, they are also a cognitive threat to social knowledge. The question inevitably arising is why are people afraid of imaginary creatures? According to Carroll, various attempts have been made to explain this fear. The two main ones are an Illusion Theory, whereby people believe that the entity actually exists in reality, and the Pretend Theory, whereby people pretend they believe this kind of creature actually exists. However, these two theories are insufficient. There should also be an intermediate theory, something that does not commit the audience to a belief in Dracula, but also leaves it in a state of genuine emotion, allowing it to experience feelings of horror. An alternative to these theories is Thought Theory. Carroll contends that when we are afraid of Dracula, we are actually afraid of the thought of Dracula, but do not commit to believing he exists. In art-horror we are afraid of the content of the thought, in other words that there is a chance, even a minute one, that Dracula – the impure creature that crosses cultural categories – might exist. In order to amplify this thought, the imaginary creature’s geographical setting is usually unknown, located outside and beyond existing borders, just like their category attribution.

Vague boundaries and the boundary between belief and thought are expressed in Van Herpen’s “Chemical Crows” collection (January 2008). The inspiration for this collection is black magic and alchemy, the desire to control existing materials, change and transmute them at will; to transfer material from one category to another, to believe in the power of crows, and imaginary stories of magic. Van Herpen, who uses metal ribs from children’s umbrellas for this collection, takes a simple raw material and tries to turn it into part of an extravagant outfit; a form of modern alchemy.

In his conclusion, Carroll contends that the previous art-horror cycle coincided with the period now known as postmodernism that advocates the deconstruction and blurring of boundaries. In this respect the rise of the horror genre in popular culture can be an expression of the growing fear over the deconstruction of traditional definitions. Art-horror is a form of creativity predicated on the dislocation of social categories through contradiction and distortion. Consequently, according to Carroll’s theory the current art-horror cycle can be interpreted as a visual version of the postmodern logic that brought with it conceptual works known for their instability. The blurring of boundaries between machine and human, between traditional and innovative materials, and between the conventional and futuristic, are clearly evident in Van Herpen’s work.

The attraction to fearIf there is indeed justification for the feelings of discomfort we experience through Van Herpen’s work, what is it that attracts us to it? Referring to tragedies, philosopher David Hume said: “It seems an unaccountable pleasure, which the spectators of a well-written tragedy receive from sorrow, terror, anxiety, and other passions, that are in themselves disagreeable and uneasy”, and sparked the debate known today as the Paradox of Tragedy/Horror. Investigation of this paradox has developed in recent years particularly due to the popular horror film genre, and is also relevant for an examination of Van Herpen’s success.

In his article The Paradox of Horror, philosophy of aesthetics scholar Berys Gaut states the three points of departure in the debate on the paradox of horror in cinema: (1) Some people enjoy horror films; (2) Horror films evoke fear in the audience; and (3) fear is an unpleasant emotion. Gaut presents different interpretations that have emerged in the course of the theory’s development, one of which is that we do not enjoy the negative feelings but rather a different aspect of the situation, such as the curiosity aroused in us concerning what is about to happen. Although he refuted this theory with respect to cinema, contending that the horror genre is based on prescribed narrative models, and consequently the end is known in advance, it is relevant for Van Herpen’s work. Based on innovative technologies, her work displays diverse forms and techniques that are considered groundbreaking. Curiosity could be one of the main reasons that push us to overcome our discomfort and draw closer to the garments in order to scrutinize them from every angle. The curious spectators inspect the seams, try to decipher the cut, examine the colors, and imagine the garment in movement.

Later in his article, Gaut argues that the simplest explanation for this paradox is that there are people who enjoy the emotions of fear and horror. However, acknowledging this establishes the paradox that we take pleasure in something unpleasant. A possible solution for this problem is the argument that when it comes to something imaginary that does not pose a real threat, it is easy to control the feeling that awakens instinctively. Spectators know that they are seeing an inanimate object, and consequently they can control their fear and channel it to the pleasure they gain from the situation.

Another solution proposed by Gaut is the separation between feelings and sensations. Feelings are not defined by sensations, and consequently different feelings can be expressed in a wide range of sensations that vary from one person to another. If we accept that feelings are a cognitive phenomenon (intellectual as opposed to physical), we can add the evaluation dimension to that feeling (when we recognize the feeling of fear we can evaluate whether this element poses danger or not). A further aspect of this separation is our ability to recognize negative feelings as negative, not because we feel bad (physically), but due to the cultural conditioning into which we have grown – a negative feeling can be explained as a reaction to the evaluation of an object that is culturally perceived as negative (snakes, bones, skeletons, black magic), and not necessarily to an unpleasant sensation engendered by the feeling itself.

According to this theory, people can enjoy negative feelings despite the conceptual linkage between them and discomfort. The ability to separate elements that are culturally fixed as threatening or impure from the aesthetic experience is a cognitive process spectators undergo when seeing Van Herpen’s designs. Even if we imagine for a moment that the bone dress is going to come to life and start walking, rattling its pelvis, or that the snake dress is going to start writhing and collapse into a pile of slithering black snakes, the intellectual evaluation going through our mind is that this is implausible, and the reason we are afraid of it is merely a cultural conditioning, and consequently, it is possible to enjoy the fear without being drawn into the horror paradox loop.

Wanted: A dress for the end-of-the-world eventVan Herpen is a rising star in the firmament of the design word, and the spectators’ attraction to her garments is absolute, an attraction that does not allow feelings of fear to hold it back. Van Herpen’s inanimate objects manage to build in spectators an emotion of fear stemming from an aesthetic work. This fear is not an original fear, but a styled, artistic simulation of what is crude, unclear, and uncontrolled in life, and is followed by an experiential process that cannot be foreseen. Biology is the inspiration; it proposes elegant, efficient solutions for the changing world. When Van Herpen marries digital technology such as 3D printing with natural forms and processes, she proposes a new, radical urban vision of objects that are not only designed in accordance with the environment, but also react to it.

Through her garments Van Herpen manages to create an explosion of ideas, thoughts, and aspirations that sometimes seem to verge on the impossible. With seemingly contradictory combinations between handcraft and technology, real and artificial, she manages to shake the ground of the fashion world. Her garments present combinations that in the past seemed implausible: fabrics consisting of silk threads combined with plastic fibers, artificial opals glinting through traditionally handcrafted embroidery, flexible 3D printing that reacts to environmental conditions, umbrella spikes sewn alongside fabrics, and so forth. Commenting on Van Herpen’s work on Style.com, Jo-Ann Furniss writes: “The overall impression was of event-wear – where the event is the end of the world”.