Hundreds of red hearts hover mid-air in the space of the exhibition “Alber Elbaz: The Dream Factory,” dedicated to the legendary Israeli fashion designer. The hearts symbolize the saying “love brings love,” which guided Alber throughout his life, and later accompanied the tribute show produced in honor of his memory after he died in 2021. In a show of solidarity that is rare in the fashion industry, 46 of the world’s top designers and leading fashion houses – including Gucci, Valentino, Iris van Herpen, and many more – came together for the tribute and created couture pieces that celebrate his memory, as a final act of love for him. Alber received great esteem and recognition from central figures in the global fashion industry and headed several world-leading fashion houses. These achievements stand in contrast to the fact that he was quite unknown in Israel. The exhibition aims to change this curious fact and expose the Israeli public to the person that Alber Elbaz was and the road he traveled to the highest peaks of the fashion world.

Hundreds of red hearts hover mid-air in the space of the exhibition. Photo: Elad Sarig

“It’s important to mention that Alber didn’t want to sum up his work. He didn’t want a retrospective,” says Ya’ara Keydar, the exhibition’s curator, about the starting point for the work on the exhibit. “He did not build an archive of his career, so there had never been a comprehensive exhibition about him and his work. When he passed away, we thought about the possibility of dedicating a large-scale exhibition to him, but as with every retrospective, the thought was that it would take several years and be more complex.

“What brought us to change course was the tribute show that Alex Koo (his partner) organized in honor of his memory. Forty-six of the world’s greatest designers gathered for one evening in Paris and celebrated his life. That same night, October 5th, I remember sitting and watching this show, image after image, and thinking that this could have been an incredible exhibition. I tried to contact the people close to Alber, but it was too soon and too early.

“Eventually, Sheli Wertheim, who was Elbar’s teacher at Shenkar College and accompanied him throughout his career for some twenty years, contacted me. She asked if I would like her to put me in touch with Alex so that the tribute show could come to Israel. I knew that this had to happen, and that it had to be at the Design Museum Holon, both because of my own collaboration with the museum – which began with the exhibition “Je t’aime, Ronit Elkabetz” and continued with the exhibition “The Ball” – and also because Alber grew up in Holon and sadly was also buried there.

The saying “love brings love” guided Alber throughout his life. Photo: Elad Sarig

“The first and most immediate option was to exhibit the tribute designs, and for that to be the whole exhibition, but I knew there was an opportunity here to do something bigger. Maya Dvash (the museum’s chief curator) and Danny Weiss (CEO of Mediatheque) gave me their full support to pursue this as an exhibition that would be unique to Design Museum Holon – in other words, one that would not only feature the designs from the tribute show but also give its own added value by telling his story and a new story.

The exhibition notes the fact that Alber was not known in Israel, which is surprising given his achievements and the heights he reached. How and when were you first exposed to him?

For my bachelor’s degree I studied fashion design at Shenkar College. For all the generations of graduates of Shenkar, Alber Elbaz was the ultimate authority, an oracle. He represented the dream that everyone aspired to. I finished my studies there twenty years after he graduated, and yet everything we did was based on how he inspired us: the idea that it was possible to make it, that you could get there no matter where you came from. Luckily for me, Alber gave a lecture to the students at Shenkar in 2005, when the college awarded him an honorary prize. On that same visit, I also interviewed with him for a job. I was then in my fourth year of school and he was looking for an assistant in his studio. In the end, I wasn’t chosen for the job, but our conversation was very good and he also helped me figure out something that was unresolved in my final project. That was our first encounter.

“When I started working on the exhibition ‘Je t’aime Ronit Elkabetz,’ Alber offered to help and to advise me on constructing the exhibit. He and Ronit were close friends, and she wore his designs in the greatest moments of her life. Shlomi (Elkabetz, Ronit’s brother, who was the show’s artistic director and in charge of its design) and I met with Alber in New York and he presented to us his philosophy regarding fashion exhibitions. It was a truly formative meeting. Later, I met with him again and recorded our conversations. When I started working on the present exhibition, I didn’t even remember these recordings. I came upon them by chance while searching my computer, and when I listened to them it was a chilling moment – I realized that I had a recording of him, in his voice, in which he was explaining to me very clearly what to do in the exhibition. In the recordings, he emphasized the importance of celebrating life in the exhibition, letting humor and the spirit lead, and not death and didacticism.”

“As a fashion historian, I know how often designers whose story was not documented could have been significant designers, no less than Coco Chanel or Yves Saint Laurent. But instead, they disappeared from the collective memory”

How do you approach an exhibition that is dedicated to a person and not an idea? Did you know what story you wanted to tell?

“This is my second experience with work of this kind, because I started with Ronit Elkabetz – whom I also, unfortunately, did not know personally. When I approach the research, I’m usually not looking for anything specific. I have learned over the years that when you don’t limit or restrict your search, that’s when the most intriguing stories can suddenly be discovered. It’s a bit like doing detective work that ultimately coalesces into a story.

“I approached the exhibition like I approach every project, which means diving as deeply as possible into the material that I find – whether it’s reading all the articles and listening to all the lectures, or looking at the clothes and letting them speak. Clothes are living objects, especially in Alber’s case. I met with people who worked with him and interviewed them, spoke to his family, teachers and friends, and heard stories about him. All of this helped me to connect to his life, to understand him and his essence. I became so immersed in his story, that at certain moments I just didn’t believe that he was gone – because to me he was so alive.”

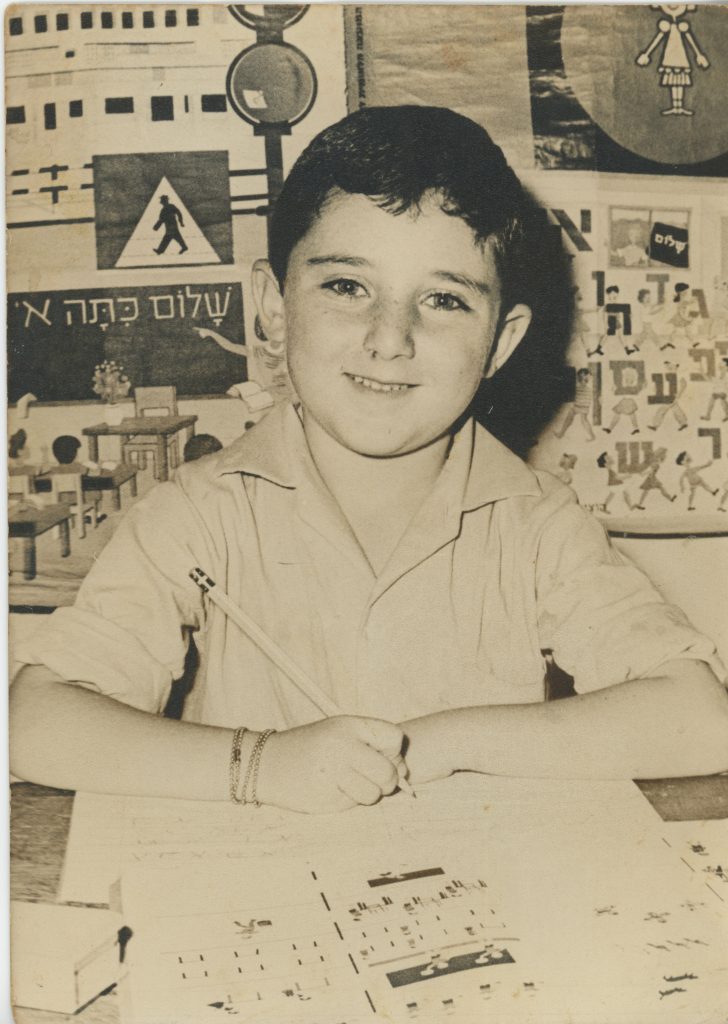

Alber Elbaz at 1st grade, in “Hameginim” school, Holon, 1967. Photo: Family album

The exhibition at the museum is filled with stories that accompany Alber’s coming of age: sketches of ensembles for women, which he drew as a child for his teachers; his dream to work for the fashion house of Yves Saint Laurent, sparked by a YSL scarf received at a family event; the exhibit follows his early experiments in the realm of fashion as a soldier re-designing the uniform, and continues to his works as a student and then to the course of his career, which was filled with many successes but also with heartaches and hardships.

Some of the materials featured in the exhibition are extremely personal and sensitive, requiring a very delicate interaction with the family. How did you gain their trust?

From the moment I met Alber’s family members, we had an immediate emotional and human bond. This was the case with Alex Koo, and with everyone who joined the project along the way. I think they sensed that my intentions were entirely for their good and Alber’s good, and that the museum was making every effort to ensure that the exhibition would honor him. We started working only a short time after his death; everything was raw. It was very sad to work with people who miss him so much, people for whom your questions are painful and handling his belongings is painful, even though they understand that it is all done for the project’s good. It’s hard to be in that place, so there is a need for quiet and giving things time.

“At the same time, everyone realized that we were at a crucial moment in preserving his memory. As a fashion historian, I know how often designers whose story was not documented could have been significant designers, no less than Coco Chanel or Yves Saint Laurent. But instead, they disappeared from the collective memory. In my view, this work has great importance for future generations, because this exhibition creates, for the first time, an organized archive and a written history of the life and work of Alber.”

Was there one story you heard from the family that touched you especially?

“When Alber’s mother was sick and hospitalized, he was living on the line between Paris and Israel and he flew to Israel to be with her. They had a profound bond. As time went by, her health deteriorated, and she passed away. After her death, he created a collection in which all the clothes looked torn to pieces and then reassembled. Maya, Alber’s niece, told me that the clothes symbolized the umbilical cord that connects Alber to his mother, and that he was always trying to put those cords back together again. The element of the tearing of the fabric connotes the traditional Jewish practice of Kriah – the tearing of a garment as an expression of grief. I already knew this collection well – some of its designs are in the collection of Ronit Elkabetz’s garments, which is held at the museum – but I had not known this story, which made me see the collection in a new light. It shook me deeply.”

“Alber had always dealt with the crises he faced: the heartaches, the job dismissals, the difficulty of starting from the lowest possible place. He exposed the complexities and discussed them openly, without trying to sugarcoat anything. His approach gave me the tools to talk about these moments, to allow them to be present”

The exhibition touches on complicated moments in Alber’s career: rejections and firing, moments of crisis in which he was forced to re-invent himself. Such moments are part of life, but it’s not obvious to talk about them with such candidness. Did you have any qualms or concerns about including them in the exhibit?

“A person’s life is a fragile and delicate thing. In Alber’s story there is genius and love and compassion and sensitivity, but also a lot of pain and fractures. I think that what provided me consistently with the permission to continue on this course was the fact that Alber had always dealt with the crises he faced: the heartaches, the job dismissals, the difficulty of starting from the lowest possible place, growing up in a rough neighborhood as a child who stood out. He exposed the complexities and discussed them openly, without trying to sugarcoat anything. We can learn a lot from him: the road to every success is bumpy, lined with failures and moments when we need to start all over again.

“His approach gave me the tools to talk about these moments, to allow them to be present. The more I immersed myself in his story, the more I saw how openly he spoke about insecurity, about the fear of showing your work, the fear that it will not be good enough or the expectation that you need to be more and more. I realized how many questions he used to ask, and the extent to which he allowed ambivalence to be part of his life. This helped me a lot in the process of this work, because I approached the process with great reverence and with a lot of trepidation. His approach helped me to ask questions and feel doubt, and showed me that it was ok to try different options and to make changes. Things are not always clear, and that’s ok, the search is essential.

“When an exhibition is about a person, we need to keep it human and complex, and this is what I really wanted to achieve here. Not just for people to come out of it and say ‘Wow, he was a genius designer,’ which he was, but for them to get to know him, to feel that they are meeting the singular personality that he was. In the Guest Book people write that they feel like they met him, and write: ‘I fell in love today.'”

What guided you in building the story of the exhibition?

“I think it was the moment when I figured out the lower gallery, the collection of AZ Factory. The moment when I realized that I would start the exhibition not chronologically but rather with the last thing that he did, by presenting this collection, which is, in a sense, the climax of his life.

“I thought about how to present the collection, and I recalled that to our meeting about the Ronit Elkabetz exhibition Alber had brought with him a book about the design of his display windows at Lanvin. It helped me understand how to do the site installation in the exhibition. Then I watched a short film he made for CFDA (the Council of Fashion Designers of America) when he was about to receive their ‘International Designer of the Year Award.’ In that clip he says: ‘My work is more about a voyage. A voyage from different stations in my life. New York and America brought me the comfort, and Paris gave me the individuality and the chic, Israel brought me the tension, and Morocco – the sands, the colors, and the spices.’

“I spread out the pictures from the AZ Factory collection on the floor in front of me, and suddenly I saw Paris with the Little Black Dress, Tangier with the colors of spices and sand, and New York with the sportswear and the comfort and flexibility. But Holon remained a bit of a question mark. I was trying to understand how to present the city. And then his family came to visit the museum. We talked about the fact that in Israel few people had the privilege of knowing Alber and the extent and reach of his work, and they said that the reason for this was that when he came home to Israel, he wanted only to be at home with his family and have pajama parties. That’s when I understood how I would represent Holon – through a pajama party. Alber designed a huge collection of pajamas as part of his AZ Factory collection because it was launched at the height of the COVID pandemic. The demand for pajamas was high at the time, and in general, this was one of his favorite items to wear. He designed the pajamas with prints that were inspired by everything he missed and longed for during the pandemic: hugs, kisses, and dancing.

“From there on, things began to happen. I started roaming through the museum and putting together the rest of the stories. I knew that the corridor was an opportunity to tell his story from beginning to end, but as an accompaniment rather than a central part of the exhibition; a kind of spine for the exhibit. The lower gallery features the AZ factory collection, the upper gallery is dedicated to the tribute show, and the remaining parts each tell a different anecdote.”

The museum’s upper gallery presents the couture pieces designed by the world’s top designers for the tribute show. Some of them drew their inspiration from the line and style of design that characterized Alber, and others drew it directly from his character, so that we see the iconic YSL bear wearing glasses and a bow tie, which are accessories that characterized Alber. Alongside each design there is a dedication from the designer to Alber, which tells about the person that he was and meaningful moments in which he took part.

Which dedication and design did you find especially moving?

“I really liked the dedication by Pierpaolo Piccioli, who recounted how when he was appointed to be the artistic director at Valentino, Alber sent him an apron that he himself had sewn for him. Piccioli noted that Alber did not do this in front of the cameras and did not document it on Instagram. It was a gesture of love from one person to another person to wish him luck on his new path.

“The design that moved me especially is the white dress created by Bruno Sialleli, who was until recently the creative director of Lanvin, the fashion house that Alber headed for 14 years until he was fired over disagreements with the management. The fact that Lanvin created a tribute in his honor testifies to the possibility of repairing and mending. The dress Sialleli designed is a white version of the famous yellow-sun dress that Alber designed for Ronit Elkabetz and which was shown in the exhibition dedicated to her at the museum in 2017; so this was truly a kind of closure, coming full circle.”

What is the meaning of the name of the exhibition, “Dream Factory”? These words are contradictory.

“A factory is a place where we labor and sweat, and dreams are a kind of fantastical, spacey place. Alber saw fashion as a place where you need to work hard, as in a factory, to show up every morning, day after day, and make the dreams come true. Without hard labor and team work, no dream can be realized.”

“Alber wanted the women who wear the garment to feel comfortable and not to have to be careful or worry that it will be damaged. In the end it’s just a piece of clothing, and the idea is that the woman herself is more important”

Alber’s Design Style

In the exhibition, there is a quote by Alber in which he says: “I don’t like perfection, I think it’s dangerous. After perfection there is nothing.” How was this expressed in the clothes he designed? What characterized his style of design?

“The clothes he designed speak of a liberation from conventions and a liberation from trends; and indeed, they stand the test of time. We see in his clothes the imperfection he inserted into them deliberately: unraveled finishes, exposed zippers, large buttons. He emphasized the garment’s utility, and made its various closures into an integral part of the design as a whole, a part of the garment’s beauty. It’s important to note that even the imperfections he included were “made to perfection” – crafted as meticulously as possible. He wanted the women who wear the garment to feel comfortable and not to have to be careful or worry that it will be damaged. In the end it’s just a piece of clothing, and the idea is that the woman herself is more important.

“In general, Alber’s design was characterized by a sensitivity toward women, and he aspired to create design solution that give you, as a woman, the feeling that someone was thinking of you: that there should be pockets, that the clothes shouldn’t be too tight in weird places, that they should allow you to sit, walk, stand up, bend down – things that clothes are often not designed to do.

“When we look at the history of fashion, we see that these details were absent from it for many years. Until the end of the nineteenth century, women’s clothes had no pockets, and comfort and practicality were not a consideration in their design. For a woman, being more restricted in walking and in donning your clothes was a sign that you belonged to a higher class and required servants to dress you. In my view, this is the significant change that Alber heralded in his work – placing the emphasis on those who live inside the garment, and not on the garment itself.

Where did his sensitivity toward women come from? It reflects a high level of attunement to the challenges of someone other than yourself.

“Alber grew up in a house of strong women, and his relationship with his mother had a powerful influence on him. When his father died, he was 17, the youngest child in the family, and he continued to live at home with his mother. Their bond gave him an understanding of the needs of women, their challenges, and what they lacked. His love for women was a constant throughout his life. He had many close friendships with women, and he knew that as a designer he had the ability to give them practical solutions.

The Stories Our Clothes Tell

After he was fired from Lanvin, Alber embarked on a journey whose goal was to explore the meaning of fashion in his life, and more generally in the world. What is the meaning of fashion to you?

“I devote my life to it. Human beings interest and preoccupy me, and the closest thing to human beings that is not perishable are the clothes we wear – they tell us so much. I believe in the effectiveness of objects and in the life within them. I believe that those who give meaning and importance to attire, leave behind clothes that tell us about it. Therefore, clothes allow us to embark on travels in time and in the imagination, and reveal to us secrets and stories that bring to life the body and the person that lived them.”

To date, you have curated three exhibitions at the museum: ‘Je t’aime Ronit Elkabetz,” “The Ball,” and the present exhibition, “Alber Elbaz: Dream Factory.” In all three, there is a theme of dreams and fantasy. What place does realizing dreams hold in your own life?

It holds a very central place. I was a dreaming child, lost in fantasies and in a world of dreams and thoughts on how to make them come true. I knew from a very young age that you had to work hard to achieve things, and that’s what I did. I think that one of the things all three of these exhibitions have taught me is how important it is to dream without limits or boundaries. In this sense, I was blessed to work with the chief curator Maya Dvash, who always provides the most expansive, free and challenging creative space. We have a fruitful and moving creative dialogue that always propels me forward.

“When I approach the work on a new exhibit, I ask myself, ‘What is the thing that I wish to share with others.’ The desire to share is a central part of what I do. I want people to enter the world I am presenting and receive something with love and generosity. In order for them to feel this way when they enter the exhibition, I have to dream as big as possible, and then to figure out how the dream is carried out in practice. As Alber once said – sometimes the dreams become nightmares and then you need to work hard to solve the problems and turn them into dreams again. I set this sentence before my eyes when I started working on the exhibition.”

What are the dreams you want to realize at the moment?

I dream that Alber’s exhibition will travel to another place in the world; I want to finish writing my PhD (Keydar is a third-year doctoral student in the Cultural Studies Program at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem); and I’m also dreaming about my next exhibition, but it’s too soon to talk about that.”